A Brief History of the Census in Scotland

Ian White, Office for National Statistics The material in this article is taken from a book that the Office for National Statistics plans to publish before the 2011 Census and which is, itself, a pot pourri of material gleaned from the official reports of the decennial censuses in Great Britain over the period 1801-2001, and from a range of other sources. |

Early Scottish Censuses

The first attempts to get an accurate picture of the population, geography and economy of Scotland were in the 1620s, using the network of ministers of the Church of Scotland. But the time and effort involved limited the results. Between 1684 and 1690, Sir Robert Sibbald, the Geographer Royal for Scotland and co-founder of Edinburgh’s botanical gardens, made further attempts by circulating ‘General queries’ through the same network of parish ministers. Though some progress was made, the results provided a very incomplete picture of the nation. In the first half of the 18th century, the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland proposed a ‘geographical description of Scotland’ and took some action on this between 1720 and 1744. But these were troubled times for the country and the proposals foundered during the second Jacobite rising.

The first successful collection of contemporary ‘census’ data in Scotland - almost a half a century before the first statutory census - was by Alexander Webster, a Scottish minister and writer, in the Account of the number of people in Scotland. Webster was born in Edinburgh in 1707 and studied mathematics at the university there before becoming, despite his nickname Bonum Magnum on account of his capacity for drinking claret, a minister of the Church of Scotland. He served at Culross in Fife from 1733 to 1737 and from then until his death in 1784 at Tolbooth Church in Edinburgh.

He gained public attention in 1742 when he proposed to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland a scheme for providing pensions for the widows of Scots clergy and of the teaching staff at the universities of Edinburgh, St Andrews and Glasgow. The proposal was taken up by Dr Robert Wallace, the Moderator of the General Assembly, through an Act of Parliament in 1743 for "raising and establishing a fund for a provision for the widows and children of the ministers of the Church of Scotland". The work of organising and administering this – at least in its early days – was given to Webster under Wallace’s careful supervision. He proved to be more than capable of the task, since the tables which he drew up from information from all the presbyteries of Scotland were based on a methodology later followed by insurance companies in calculating longevity.

As a result, and on his own election as Moderator in 1753, Webster was invited to make an enumeration of Scotland’s population at the request of Robert Dundas, 3rd Lord Arniston when he was Lord of the Court of Session (or perhaps it was his more illustrious son when he was Lord Advocate - the record as to which is not quite clear). So Webster wrote in 1755 to over 900 ministers, from lists developed from the earlier 1743 enquiry, requiring them to submit population returns for their parishes identifying age, sex, fighting men, protestants and papists. His request was reinforced by a threat to withhold funding for charity schools in any parish which failed to comply. In his introduction to the Account, Webster, writing in the third person, noted that:

"As few parishes in Scotland keep district Registers of births and burials, the author was obliged to have recourse to a more laborious tho’ more certain method of finding out the number of inhabitants………….

By this means and by various other methods taken to prevent mistakes, he obtained certain information of the exact number of souls, throughout a great part of the Kingdom, and particularly in the more northern counties including the whole Highlands and Islands".

He arrived at a population for Scotland of 1,265,380, of whom 488,652 were under 18 and 125,899 were over 56. Webster had to make estimates of the population of parishes for which he did not receive complete replies to his enquiry. But, despite uncertainty about the precision of the figures, the care that Webster and the many ministers took in its compilation and the pioneering nature of the work make it understandable that Webster claimed (again writing in the third person) that:

"… the Account he has given of the Number of the People will be found to come very near the truth, and to be sufficiently exact for answering every valuable purpose"

Webster’s census was a pioneering work in the British Isles. It remained significant for those who followed him: it was transcribed by James Crauford Dunlop (Registrar General for Scotland from 1921 to 1930) and an analysis of its findings by James Gray Kyd (Registrar General for Scotland from 1937 to 1948) was published by the Scottish History Society in 1952.

Webster’s work was followed up by a national survey ‘parish by parish’, proposed by the eminent economist Sir James Denham Steuart in 1767 in his Enquiry into the principle of Oeconomy, and which was later taken up by the noted eccentric David Stewart Erskine, 11th Earl of Buchan in 1781 in his proposals for:

"a general parochial survey of Scotland in order to further historical understanding and advance national improvement."

However, only a few parishes were ever surveyed by Erskine, and by the time that the limited results were published in 1792, it had been overtaken by the far more substantial work of Sir John Sinclair of Ulbster as part of the First Statistical Account of Scotland.

Sinclair (1754-1835) was a politician and writer on finance and agriculture. He was the eldest son of George Sinclair of Ulbster, a member of the family of the Earls of Caithness, and was born at Thurso Castle, Caithness. After studying at the University of Edinburgh, University of Glasgow and Trinity College, Oxford, he was admitted to the Faculty of Advocates in Scotland and called to the English bar, but never practised. In 1780, he was returned to the House of Commons for the Caithness constituency and subsequently represented several English constituencies, his parliamentary career extending, with few interruptions, until 1811. His reputation as a financier and economist had been established by the publication, in 1784, of his History of the Public Revenue of the British Empire, and in 1793 national ruin was prevented by the adoption of his plan for the issue of Exchequer Bills. It was on his advice that, in 1797, William issued the ‘loyalty loan’ of £18 million for the prosecution of the war against France.

Sir Henry Raeburn, Sir John Sinclair, 1st Bart of Ulbster, National Gallery of Scotland

But his services to agricultural science were no less significant. Because of his interests in the improvement of estate management (for which he was popularly known at the time as ‘Agricultural Sir John’) and, as first President of the Board of Agriculture, he set out a proposal to develop Steuart’s and Erskine’s ideas by conducting a detailed parochial survey to ascertain "the natural history and political state of Scotland". In May 1790, Sir John sent structured questionnaires, containing over 160 questions, to the network of over 900 parish ministers. These questions covered for each parish the geography, topology and climate, its natural resources and natural history; the population and related matters; agricultural and industrial production; and a miscellany of other data.

Not all ministers replied at first and by June 1792 Sinclair was still awaiting returns from some 400 ‘deficient clergy’ as he called them. He was then forced to write letters whose tone changed from earnest flattery to cold scorn and impatience and, for the most persistent refusers, he resorted to thinly-veiled pecuniary threats and even threatened enforcement by billeting soldiers from his own private militia – the Rothesay and Caithness Fencibles. In June 1796, Sinclair sent out ‘statistical missionaries’ to follow-up the most stubborn offenders. This persistence was eventually effective. The project was complete by 1799, and Sir John was able, by the end of century, to lay before the General Assembly in 21 volumes:

"a unique survey of the state of the whole country, locality by locality".

Nothing similar had been attempted in Britain since the Domesday Book, and nothing at all on such a scale in Scotland. A flavour of the style and content of the abstract can be seen in the contribution offered by the Reverend James Thomson on the Parish of Aberlour in the County of Banff (an example chosen because of the author’s particular love of the local malt whisky – though there was yet no distillery there at that time):

"According to Dr Webster's state of the population, the number of inhabitants was 1010. There are, at present, about 920 souls; about 450 males, and 470 females. The births and deaths bear not the ordinary proportion to the population. By summing the baptisms and burials for 20 years, that the baptisms are, at an average, 25, deaths 13, and marriages 8. Though there are scarce any remarkable for longevity, yet the people are generally healthy, and, a few excepted, who are carried off by small pox and consumptions, arrive at the age of 70, 80, and not a few at 84. The whole are of the Established Church, except about 10 or 11, who are Roman Catholics. The inhabitants, except a very few servants and cottagers who come from Strathspey and Badenoch, are natives, descended from ancestors who have lived in the parish for many generations; and as there are very few who come from other places, so there are as few who leave the parish: For since the year 1782, when there were whole families emigrating from the neighbouring parishes to North America, none, except a few aspiring young men, who have had a more liberal education than their neighbours, have left this parish, and gone, some to London, some to the West India Islands. There is but one residing heritor."

Thus Sinclair’s Statistical Account, though building on the several previous incomplete or failed attempts to gain an accurate picture of the state of the nation, represented a new beginning for the understanding of Scottish, and indeed British, population and society.

Though the returns were neither compiled nor published at the same time, so disqualifying the enquiry as a ‘census’ in the way that we understand the concept today, they had the great merit of being prepared locally by those with the best local knowledge. Incidentally, Sinclair is recorded as being the first person to use the word ‘statistics’ in the English language. In volume 20 of his Account he explains:

"Many people were at first surprised at my using the words "statistics" and "statistical", but in the course of a very extensive tour through the northern parts of Europe which I happened to take in 1786 , I found that in Germany they were engaged in a species of political enquiry to which they had given the name "statistics", and though I apply a different meaning to the word – for by ‘statistics’ is meant in Germany an inquiry for the purposes of ascertaining the political strength of a country or questions respecting matters of state, whereas the idea that I annex to the term is an inquiry into the state of country for the purposes of ascertaining the quantum of happiness enjoyed by its inhabitants and the means of future improvement. As I thought that a new word might attract more public attention, I resolved on adopting it, and I hope it is now completely naturalised and incorporated with out language".

Later at the age of 80, and just a year before he died, Sinclair became the oldest founder member of the Statistical Society of London – now the Royal Statistical Society.

The 1801 Census

It was not until the start of the 19th Century that regular censuses, of the kind we know today, were carried out in Scotland or any other part of Britain. In 1753, there had been an unsuccessful attempt to pass a Bill in Parliament authorising an annual census throughout Britain It was opposed, mainly by those who feared that the results might disclose to foreign enemies the weakness of the country, or that it would impair the liberty of the individual. The Bill was approved by a large majority in the Commons but the Parliamentary session ran out, and the Bill lapsed and was never re-introduced.

But it was becoming clear during the latter part of the 18th Century that the population was increasing. Concern about the effect of that increase on food production, emigration and colonisation, reawakened calls for a census – spurred by a critical food shortage due to a succession of poor harvests at the end of the 18th Century (including a particularly disastrous one in 1800) and a shortage of agricultural workers because many were serving in the militia in the war against France. A second Census Bill came before Parliament later that year and had an easy passage. The arguments for the census during the course of the debate included:

The Act was designed explicitly for the whole of Great Britain, though differences in the local administration between Scotland and England (as well as differences in the climate!) meant that the two censuses were conducted quite separately. In England and Wales, the Overseers of the Poor were appointed to act as enumerators, assisted where necessary by church officials or constables. But in Scotland the responsibility was placed on schoolmasters, who were to deliver the census questions after 10 March (the earliest that a census in Great Britain has ever been taken) and submit the completed returns by 24 October.

The 1801 Census was divided into two parts. The first, carried out by the enumerators, sought to collect the numbers of males and females, people employed in agriculture, trade, manufacturing, handicraft, or other work, inhabited and uninhabited houses, and families. The replies to the question on employment were not consistent. In some cases, women, children and servants were classified with the householder and in other cases they were included as ‘others’. The family was still regarded as a single economic unit, and the concept of an individual with his or her own occupation separate from the family was unfamiliar.

The second part of the census looked at whether the population was increasing or decreasing. The clergy were asked to give details from their records of baptisms and burials over the preceding 100 years, and of marriages from 1754 to 1800. At each subsequent census up to and including 1841 the clergy in England and Wales were required to make similar returns for the preceding decade. However, because of the paucity of the parish returns in Scotland in 1801, no attempt was made to collect this information north of the border either in 1811 or 1821.

John Rickman (1771-1840), who was previously a clerk in the House of Commons, and who had been closely involved in the preparation of the Census Bill, was appointed to prepare the abstracts and reports not only for this first census but also for the next three.

In Scotland the information was collected at any time between 10 March and 1 June resulting in possible double counting. Rickman, writing his observations in the Report of the 1801 Census, justified this since:

"in the colder climate …. it was not certain that all parts of the country would be easily accessible so early in the year"

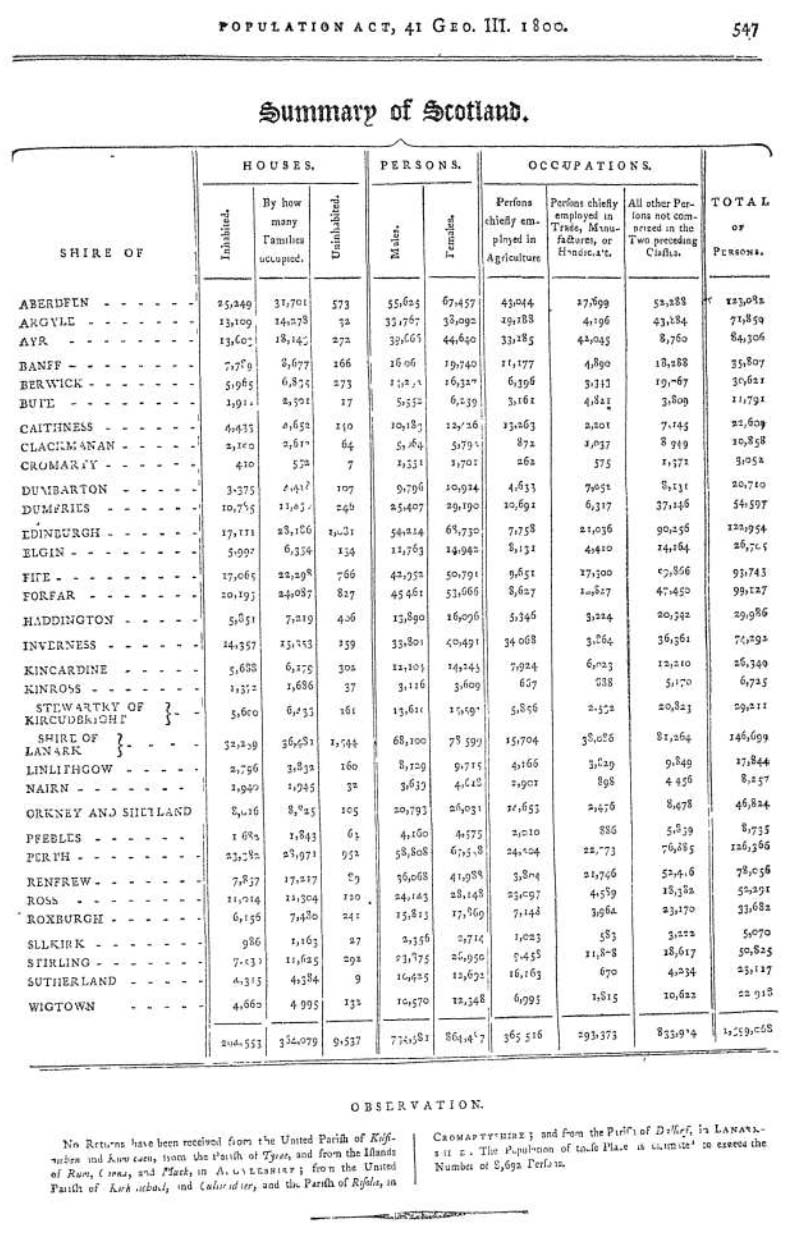

By modern standards, the whole census operation was completed in a remarkably short time. The first abstracts were printed and laid before Parliament on 31 December 1801 – a year to the day after the Bill received Royal Assent. Rickman’s results for Scotland produced a total population of 1,559,068.

1811-1831 Censuses

The 1801 model was generally followed for the next three ‘Rickman’ censuses. But there were some changes in content, reflecting the lessons learned by Rickman from his analysis of the 1801 data.

In 1811, a distinction was made between houses being built and those uninhabited for other reasons. As a consequence of the inconsistency in the 1801 responses on employment, information was collected about families engaged in occupations rather than people.

In 1821 there was the first attempt to analyse the age of the population. This was important for a number of reasons, particularly because of the growing demand from Friendly Societies for accurate life tables. Information was sought for quinary age-groups and the enumerator was instructed to collect the information only:

"…if you are of the opinion that in making the enquiry the ages of the several individuals can be obtained in a manner satisfactory to yourself and not inconvenient to the parties …"

The question on age was not repeated in 1831, because Rickman considered that there was no need to update the 1821 age distribution. But enumerators were instructed to enquire into the cause of any ‘remarkable difference’ in the number of people present in each household compared with 1821. The 1831 Census also sought more details about occupations of males aged 20 and over - the start of an occupation classification still recognisable today:-

Rickman, who had done so much to establish the census, saw the establishment of the General Register Office in England and Wales in 1837 and then handed over his census duties to the first Registrar General for England and Wales, Thomas Lister. Rickman died before the 1841 Census was conducted, though it was largely his plans for the new census that Lister carried through.

Incidentally, exactly what actually happened to the official returns for the 1831 and earlier censuses after Rickman had finished with them is not clearly recorded. There is some evidence that Rickman kept some in his own possession but by 1846 they were reported to have been deposited in the Tower of London and by 1862 they were in the new Public Record Office repository at Chancery Lane in London. In 1904 a joint Public Record Office/Home Office review recommended that the returns be destroyed since most of their contents had been reproduced verbatim in the published reports and because pressure on space at Chancery Lane was mounting. We must presume, therefore, that this is what happened since there is no further record of them.

1841 Census: the first ‘modern’ census

Like Rickman before him, the first Registrar General, Thomas Lister, proved to be meticulous in planning the 1841 Census. No longer were the Overseers of the Poor to be the enumerators in England, but rather the local machinery of the new registration service was employed. The equivalent service was not set up in Scotland until 1855 so, as in previous censuses, the deputy sheriff of each county acted as registrar, and the schoolmasters as the enumerators.

The 1841 Census was on a grander scale than any of its predecessors. It was the first ‘modern’ census in that it broke from the Rickman pattern of returns recorded locally in summary form only and then sent to London in a digested format Instead, a separate form was provided for each householder to complete and the names and characteristics of each individual were listed.

Lister initially planned that enumerators would still collect the information themselves by house to house enquires as Rickman had done. He believed that most householders were too illiterate to fill in the census schedules properly. He was only persuaded after a test in London had shown how many more enumerators would have to be employed to record the same information. The use of household schedules had to be hastily authorised by a supplementary Census Act passed only two months before the enumeration was due to take place. The enumerator had to ensure that, as far as possible, the form was complete, and then he had to transfer the answers to his own record book. The full returns themselves were then sent to London for analysis.

Drawing on some of the recommendations of the Statistical Society of London (later to become the Royal Statistical Society), the enumerators collected a much wider range of information than hitherto. In addition to the 1831 questions, the form included new questions on foreign born and nationality, and the 1821 question on age was re-instated. Although the form was simple by modern standards, at a time when a large number of people were indeed, as Lister imagined, illiterate, it was remarkable that householders, even with the help of enumerators, were able to answer the questions.

The system adopted in 1841 stood the test of time and remained essentially unaltered for the next 160 years. For us today it is difficult to imagine what a tremendous feat it must have been for the General Register Office to process the 19th Century censuses with hundreds of clerks carefully tabulating, with their pens and black leaded pencils on large sheets of paper, the details of every individual in the country.

1851 Census

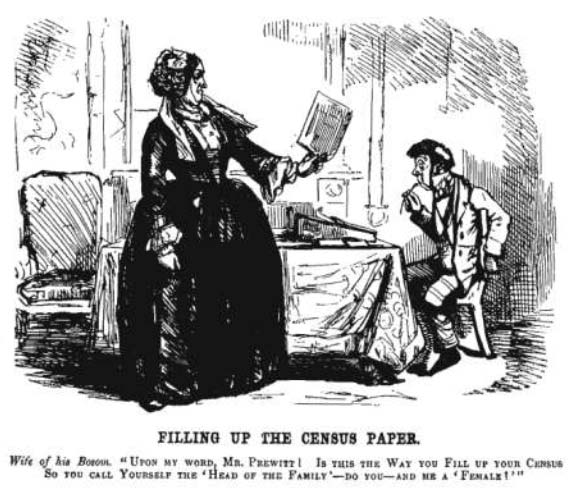

The 1851 form was substantially expanded and collected information in a more rigorous way. Addresses had to include house numbers rather than just street names, and there were questions on exact age, marital status and relationship to head of household – the latter giving rise to this Punch cartoon:-

New questions on birthplace and infirmity were also included. So much more detail was asked about occupations - even about second occupation - that an occupational classification was required. This was the first scientific attempt to produce such a classification and was to have long-lasting implications for statistical and socio-economic analysis, remaining basically the same until the 1921 Census. William Farr (who was the General Register Office’s first ‘compiler of abstracts’ and who became the 19th Century’s most pre-eminent social demographer and epidemiologist) used the information to classify people by occupation and age. The analysis, which covered 332 occupations by five year age-groups, was an enormous task. But the resulting information, together with data from death registration, made it possible to produce, for the first time, a study of occupational mortality. Among his conclusions he noted that:

"Miners die in undue proportions, particularly at the advanced ages when their strength begins to decline ….. Tailors die in considerable numbers at the younger ages of 25-45 …… Labourers’ mortality is at nearly the same rate as the whole population, except in the very advanced ages, when the Poor Law apparently affords inadequate relief to the worn-out workman."

1861 Census

From 1861 onwards, the census in Scotland was administratively separate from England and Wales following the appointment of the first Registrar General for Scotland in 1854 and the introduction of the civil registration service in 1855. There was a separate Census Act for Scotland in 1860 and the census was run from the new Scottish General Register Office in New Register House at the east end of Edinburgh’s Princes Street.

The content of the 1861 Census in Scotland was, unsurprisingly, little different from that in England and Wales, and officials at the General Register Office in Edinburgh were supplied beforehand with the English forms and instructions so as to achieve the greatest degree of comparability. However, one feature of cross-border disharmony reported in the 1861 Scottish Census Report, which was to become a feature of the Scottish reports throughout the rest of the century, was a discussion about the definition of a house. The term ‘dwelling house’ was explicitly defined in the Scottish 1860 Census Act to include:

"all building and tenements of which the whole or any part shall be used for the purposes of human habitation"

whereas the English definition was:

" a distinct building separated by party walls",

a definition that Dundas, taking Scottish architectural practice into account, thought unintelligible He reported how ‘party walls’ - though a term not defined - may bisect blocks of houses and even individual dwellings.

There were two other notable differences between the questions asked in Scotland and those in England and Wales. First, Scottish enumerators enquired whether there were people who were temporarily absent from the household on census night This was intended to identify the number of fisherman absent at sea. The results showed that some 22,000 men and 12,300 women were not present in their own household and that, respectively, 18,400 and 17,500 were temporarily present elsewhere in Scotland - the differences only partially relating to fishermen but mainly to other temporary migrants. More importantly, a question was included about the number of rooms with windows, in order to cast light on overcrowding. The census report noted that, on average, each room with a window was occupied by 1.7 people. The question was repeated in successive censuses until 1951, with England and Wales following the Scottish lead in 1891.

William Pitt Dundas would divide his day between the posts of Registrar General and Deputy Clerk Register, at the insistence of the Treasury, who were keen to cut administrative costs in Scotland. He would also spend lengthy periods in London and travelling abroad. But Dundas insisted that he should be supported in his work by a qualified Superintendent of Statistics. The work of the eminent William Farr in London was paralleled in Scotland by Dr James Stark. Though the 1861 Census reports may have adopted the pattern of previous censuses, the Scottish vital statistics were presented somewhat differently from those of England and Wales, and the Registrar General’s Annual Reports (written by Stark) had much to say about social conditions in Scotland.

In keeping with the Treasury’s desire to reduce administrative costs in Scotland, the cost of the 1861 Census, at £18,400, was almost £8,000 less than its predecessor managed from London.

The Late Victorian Censuses

William Pitt Dundas oversaw the 1861 and 1871 Censuses. He retired in April 1880. But when Roger Montgomerie, who succeeded him, died suddenly of enteric fever six months later, Dundas returned temporarily to his old office to oversee the preparations for the 1881 Census until Sir Stair Agnew was appointed as Registrar General in January 1881.

The content of the census remained essentially the same throughout the latter decades of the century. But some important questions were added.

The 1871 Census included a question on the unemployed (though no analysis of this information was provided in the statistical commentary) and the 1901 Census enquired into the number of people in certain industries who worked in their own home. In the report on occupation for that Census, females with an occupation were, for the first time, analysed by marital status.

The 1881 Census was the first to include a question on the Gaelic language. A question on the Irish language had been included in the 1861 Irish Census, and the Gaelic Society of Inverness, established in 1871 to promote the use of Gaelic and halt its perceived decline, urged the Home Secretary to include a similar question in Scotland on the grounds of:

"the well-being of the people of the Scottish Highlands and …… the promotion of education in that part of the country."

No such a question was included in the Census Bill initially introduced in Parliament. But the Gaelic Society, together with the Federation of Celtic Associations of Scotland and the Committee of the Free Church of Scotland in the Highlands, persuaded Mr Fraser Mackintosh MP to suggest the inclusion of a question asking about people who could speak only Gaelic, or Gaelic and English. No amendment was actually proposed at the time and, indeed, the Census (Scotland) Act 1880 received Royal Assent with no provision for such a question. However, the 1881 Census form did include a question, added after the final preparations for the census had been made, by overprinting the schedule in red in the question relating to birthplace the instruction:

"Gaelic to be added opposite the name of each person who speaks Gaelic habitually"

Its position on the page, and the omission of any reference to it from the notes for the householders, may well have made it more difficult for the form-filler to answer, particularly as the use of the word ‘habitually’ may have been misunderstood. So it is likely that the returns for the question were incomplete. Certainly the Gaelic Society thought so, and complained that the number of habitual Gaelic speakers reported as being 231,000 was well below the 300,000 it had suggested. However, the evidence from the census certainly strengthened the demand for more time to be allocated to the teaching of Gaelic in Scottish schools, and a grant became available shortly afterward for the purpose. A question on Gaelic has been explicitly included in all subsequent Scottish censuses.

Questions had been asked in the 1851 and 1861 Censuses about blind and deaf-and-dumb people, but in 1871 the categories of ‘lunatic’ and ‘imbecile’ were added to the list of the infirm, and distinctions were made between the different type of mental state:

However, in deference to political correctness of the day, in 1901 the term ‘idiot’ was replaced with ‘feeble minded’.

By the time that Sir Stair Agnew had carried out the 1901 Census, the population of Scotland had more than doubled from 1.6 million a century earlier to 4.5 million.

The 1901 Census Staff

1911 Census

The most important innovations in the content of the 1911 Census were the introduction of separate questions about occupation and industry, and a special enquiry into marriage and fertility, resulting from the concern at the time about the effect of a declining birth rate since the 1870s. The large number of questions was lampooned by the Scots writer Neil Munro in a short story Erchie and the Census:

"Having filled in all the details regarding the Duffy family, Erchie winked at his wife and proceeded to invent a variety of interrogations which ….. the Registrar-General had omitted from the schedule.

"Ony cats, dogs, canaries, or other domestic pets?" he asked

solemnly.

"Michty!" exclaimed the coalman. "I didna think they would

cairry the thing as far as that. We hae a cat – a – a

kind o’Tom, like".

"Cat – Thomasina," said Erchie, with a graphic pretence at

writing down this interesting item. "Whit spechie?"

"Torty-shell."

"Torty-shell, richt! Hoo mony pianos, gramaphones, motor-caurs,

or other musical instruments?"

"The only musical instrument we hae in the hoose is

Maggie’s mandolin, and she doesna play on’t," said

Duffy.

"A mandolin’s no’ a musical instrument within the

strict meanin’ o’ the Act, we’ll hae to put it

doon under Infirmities," said Erchie scribbling away with a dry

pen."

The outbreak of war in 1914 interrupted the preparation and publication of the usual reports. The detailed tables for Scotland were never published, but the Report on the 1911 Census of Scotland, in which only abstracts were published, noted that:

"The original tables, though unpublished, will be preserved in the Registrar General's Department, and will be available for purposes of statistical study to any interested in them".

The 1911 Census was also the first where enumerators in England, Wales and Ireland did not have to transcribe information from the schedules into their own record books, and the form completed by the householder has remained the master entry. In Scotland, however, when researchers and genealogists access the records on-line in 2011, they will still see the enumerators’ transcripts as in the previous censuses: the original household returns were not preserved until the 1921 Census.

The 1911 Census was a watershed: punch card and mechanical sorting were used to process the data collected. This speeded up the operation and enabled new and more detailed statistical analyses to be made. Adopted from the Hollerith technology used in the 1890 US Census, the punch card had 36 columns in which the operators recorded the coded information by round holes in numbered positions so that a machine could sort and collate all the cards which were similarly coded.

The new method of processing not only enabled the census results to be provided in much greater statistical detail but also made it possible for the data to be re-sorted to overcome the problems associated with the subsequent, and frequent, realignment of local government boundaries. It allowed the previous practice of publishing the census results in topic-related volumes to be replaced by the presentation of results for each city and county separately.

By the time of the 1911 Census, the early Victorian census records had been used for a new purpose. In 1908, the Old Age Pensions Act was passed and, for some elderly applicants who could provide neither birth, baptismal nor marriage certificates, entries from the relevant census returns were accepted as proof of age and identity. At first the English Registrar General was very reluctant to provide this service, contending that:

"This is not the purpose for which the Census has been taken, and in any case, there are practical difficulties in searching the early record books."

Ultimately though, special forms and procedures were drawn up for the purpose. In the following year, 1909, the record books for the 1841 and 1851 Scottish Censuses were transferred to Edinburgh at the request of the fifth Registrar General for Scotland, Sir James Patten McDougall. These earlier Scottish returns had been processed by the General Register Office in England and kept in London, where McDougall discovered them buried away in some ‘cellars in Westminster’.

1920 Census Act and the 1921 Census

Until 1920, each census had been carried out under its own special Act of Parliament. After more than a hundred years, the census had become established as a regular and necessary institution and its basic structure - and the topic content - had changed little over the previous three censuses. So, urged on by the Registrars General, Sir Bernard Mallett in England and Wales and Sir James Patten McDougall in Scotland, a permanent Act of Parliament was passed, removing the need for separate primary legislation for each census: Parliament would authorise each census more simply by a secondary Order. Moreover, at a time of rapid demographic and social change after the First World War, the new Act allowed for the census to be taken every five years (though only once – in 1966 – has this power been used). The Census Act 1920 is still in force today, albeit with some amendments along the way.

It had been intended to take the 1921 Census on 24 April. But a strike by coal miners, railwaymen and transport workers threatened successful enumeration throughout Great Britain. So it was decided to postpone census day until 19 June - the only occasion when the date of the census has had to be changed. But the later date turned out be less satisfactory since many people were on holiday and were missed altogether.

The decision to postpone the Census was taken only days before the original date. Over 11½ million schedules had already been printed and distributed, and these contained time-specific information about precisely when people were to fill in their forms and hand them over to the enumerator. The problem taxed the new Registrars General Sylvanus Percival Vivian in England and Wales and Dr James Craufurd Dunlop in Scotland. Either they had to reprint the schedules at a huge cost or provide supplementary information to each household. Vivian was advised that for a cost of just £2,000 he could have an amendment slip quickly produced showing the revised date and, to save taxpayers’ money, advertising space on the back of the slip could be sold. Vivian realised that not only could he offset the cost of printing the leaflets but even some of the costs of the postponement of the Census itself. The Treasury approved the plan. But the advertising was for the Sunday Illustrated newspaper and serious concerns were expressed, including a letter to the Registrar General from the Wesleyan Methodist Church, complaining:

"The fact that a Sunday Newspaper should be advertised on a government document seriously offends the conscience of a large number of people…. Registrars and enumerators feel keenly the indignity of having to distribute an advertisement of a Sunday paper"

As a consequence of this experience, no advertising has since been carried on any census material.

The question set was changed for the new Census. The age question asked for date of birth rather than exact age, to improve the accuracy of response. The long-standing question on infirmities was dropped because it no longer gave reliable information. In view of the depth of the enquiry into fertility and marriage in the 1911 Census, these too were omitted, giving way to other topics which were considered to be more relevant. The report on the 1911 Census had said that there was a practical limit to the number of questions which householders could be expected to answer, and around 25 was regarded as the limit. However, in the immediate post-war years there was growing concern with traffic problems arising from the trend for people to live further from their workplace, so the 1921 Census was the first to include a question on place of work, to help measure commuter flows, and name of employer, to enable industry to be better coded.

A major new enquiry related to the ages and numbers of children, to assess dependency and orphanhood, and the results from this were particularly helpful in the preparation of the financial framework of the Widows’, Orphans’ and Old Age Contributory Pensions Act 1925. There were also new questions about full- or part-time education, following the development of secondary education at the start of the century. From 1921, the census has asked increasingly detailed questions about educational qualifications.

A major development in the 1921 Census was the further revision of the occupational classification. The practice of officially classifying the population by occupation had been developed by William Farr in the 1851 and subsequent censuses. However, it was only in the 1911 Census that the concepts of occupation and industry were distinctly recognised, and a scheme of 'social classes’ was designed, with three basic social classes (the upper, middle and working classes), two intermediate groups between these classes and three industrial groups for those working specifically in mining, textiles and agriculture. In 1921, this class scheme was substantially revised – a revision made possible by the introduction of the first proper classification of occupations with the encouragement of the Royal Statistical Society. The three industrial social classes were re-allocated between the other classes and the new five class scheme was used primarily for the analysis of infant and occupational mortality and fertility. Thus were inaugurated the Registrar General's Social Classes, re-named Social Class based on Occupation in 1990 and totally revised in 2001 to form the National Statistics Socio-Economic Classification (NS-SEC).

1931 Census

In the 1931 Census, a question on usual residence was introduced, to enable counts to be made of the resident population which would be closer to the definition of the population base used for the population estimates than was the traditional ‘persons present’ count. Until then, the best approximation to the resident population could be achieved only by taking the census on a Sunday which, it had been generally believed, was the day when it was most likely that residents would be at home. By the early 1930s, however, greater mobility was making it increasingly difficult to find a single date during the year at which local populations could be regarded as being unaffected by inward and outward movement hence the need to experiment with a question on usual residence. The practice of holding the census on a Sunday, however, has remained ever since.

Reflecting the high levels of unemployment in the years of severe economic depression in the late 1920s and early 1930s, the Census asked about the former occupation and industries of persons who had not been employed for a long period nor who had any prospect of employment in that industry in the future.

But some questions in the 1921 Census were omitted in 1931 - about education, dependency, orphanhood, houses being built, and place of work. This was linked to a plan to hold a census in 1936, taking advantage of the new power in the 1920 Census Act to hold a census every five years. It was reasoned (as indeed was envisaged at the time when the Census Act was being drafted) that different questions could be asked in alternate censuses, thus lightening the burden in any one census. The plan was to ask fewer questions in 1931 than in 1921, which was regarded has having been at the limit of public acceptability, and reinstating other questions in 1936. In the event, however, no census was taken in 1936 and, with the intervention of the Second World War, there was to be no full census again for another 20 years.

In 1931, public broadcasts via the medium of the new-fangled ‘wireless’ were used to publicise the census. The importance of using the press in the 1921 Census to explain the purpose of the Census had been recognised, but the development of radio broadcasting made it possible in 1931 to give out, orally and nationally, a wide range of information. The BBC arranged 6 weekly talks on Numbering the people prior to Census Day on 26 April. These covered such subjects as:

The series concluded with a broadcast on census night itself by the Registrar General giving advice about how to fill up the census form. Without doubt, they played a valuable part in educating the public and encouraging them to participate. In Scotland, with the co-operation of the Education Department and local education authorities and teachers, arrangements were made for giving lessons on the census in schools. Together, these initiatives resulted in what the Registrar General later described as:

"… a gratifying improvement in the quality of the Census Returns".

The 1939 National Registration

Preparations for taking the 1941 Census were interrupted by the outbreak of war on 3 September 1939 and the census never went ahead. The National Registration Act 1939, which set up a national register for the issue of identity cards, authorised the Registrars General to compile the register using the administrative machinery already being prepared for the census. But the new registration recorded far less information than the census – simply name, address, sex, marital status, age and occupation. Some statistics from the 1939 register were published in 1944, but they were not comparable with those from previous censuses.

The 1951 and 1961 Censuses and the dawning of the computer age

The first post-war census was far wider in scope than any of the earlier ones, despite Sylvanus Vivian’s view in 1931 that the limit of the public’s acceptability had been reached in the 1921 Census. The fact that there had been an interval of twenty years since the previous census in Scotland, in which time there had been significant legislative and social changes, no doubt justified such a large enquiry. Almost all the questions that had been asked in the 1921 and 1931 Censuses were included again, plus new questions to identify full- and part-time employment and age at which full-time education was completed. New questions about the exclusive or shared use of household amenities were also included, in an attempt to assess and improve the quality of post-war housing.

An important innovation in output from the 1951 Census was the extraction of a one per cent sample of all records which was used to provide early preliminary figures on all topics in advance of the main results.

The most significant new feature of the 1961 Census was the use of a computer to process the results. The decision was made in 1957, when manufacturers were invited to put forward proposals. In all, seven companies submitted proposals. It seemed at first that the needs of the census might be met by a relatively small system that would not require the use of magnetic tape. However, it soon became clear that far more was required. During the following year, the Ministry of Defence decided that an IBM 705 system should be obtained for use by the Royal Army Pay Corps that would have a magnetic core storage of 40,000 characters backed by a magnetic drum capable of holding a further 60,000 characters. It was used to process the census results for Scotland as well as England and Wales. It was thought that, as the IBM 705 was considerably more powerful than the alternatives that were then being considered, there would be sufficient spare capacity for the machine to process the 1961 Census in its ‘spare time’, with a modified programme to cope with processing the data from the Scottish Gaelic language question. Despite the use of this latest technology, there were major delays in the final publication of the results. Though the preliminary report was published within two months, the first county report did not appear until March 1963, and it was 4_ years before the computer processing was complete and 5_ years before the final national tables were published. In the event, 72 man years were spent in programming compared with the 32 initially estimated.

A second major development in the 1961 Census was the introduction of field sampling methods. It was decided that, in view of the anticipated faster production timetable for the main outputs, a sample of records to provide preliminary figures, as in 1951, was not justified. Instead, consideration was given to the production of census results for certain topics on a sample basis only. This would clearly have the benefit of helping to reduce the cost of the census, though at the expense of a reduction in statistical accuracy, particularly at the smaller area level. The conclusion was that census counts that were necessary at the local area level, such as age, sex, marital status, birthplace and nationality, should be tabulated in full, but that a 10 per cent sample would suffice for some other variables, which were harder to code and more generally used only at the national level. Rather than carrying out a full enumeration but processing only a sample of the topics, the opportunity was taken to lessen the burden on the public by adopting a long and short form for the first time. The long form contained the full range of questions and was slipped into the enumerators’ packs of shorter forms as every tenth form. In this way it was hoped that the 10 per cent sample of households in each enumeration district would be chosen randomly and without the bias that might occur through the enumerator’s tendency to start delivery at a corner dwelling. Unfortunately, these plans were not entirely successful: there was evidence that, when the enumerator failed to deliver a long form to the designated address, it was often delivered next door instead.

The full list of questions included in the 1961 Census was even longer than the set covered in 1951 but, through the introduction of the field sampling, nine out of ten households were required to provide far less information than at any previous census since 1891. New questions were included on the long form on tenure of accommodation, professional qualifications (at the particular request of the Minister for Science, to establish the location of the country’s scientific manpower), address one year ago and number of years lived at usual residence (to throw further light on the level and direction of internal migration) and persons usually resident but absent on census night (to enable household composition to be calculated on a usual residence basis).

In addition, enumerators were asked for the first time to identify whether a building was wholly or partially residential and whether it contained more than one dwelling. The question about fertility, which had previously been restricted to married women aged under 50, was extended to all women who were, or had been, married.

Advantage was taken of broadcasting by referring to the Census both in news items and in popular programmes such as the long-running radio soap The Archers, and by featuring short light-hearted fillers between television programmes during the run into the census. The experiment of product placing the census into regular programming was not generally successful, but one programme did lend itself to the idea when an enumerator demonstrated her mime on Eamonn Andrews’ popular Sunday night show What’s My Line. As Michael Firth, the Registrar General for England and Wales, noted in the 1961 General Report:

"The effect of her appearance on the previous evening was to ease the enumerators’ job of distributing schedules on the Monday. No longer were there blank apprehensive and enquiring householders; instead there was ready co-operation when the enumerator called."

1966 Sample Census

The 1920 Census Act allowed for a census to be taken every five years but the Registrars General had continued to rely on the decennial census to meet the needs of users. The rapidly-changing demographic profile in the 1960s - with increasing birth and migration rates and greater mobility - together with the need for more up-to-date information than that was provided by the delayed results from the 1961 Census, prompted the decision, around the end of 1963, to carry out a mid-term census in 1966.

To reduce costs, however, it was proposed that the census should be on a 10 per cent sample basis for the whole of Britain, except for six Special Study areas in Scotland that were to be fully enumerated In England and Wales the sampling frame was a list, taken from the 1961 Census, of one in ten structurally separate private dwellings and small communal establishments (such as hotels which were expected to have fewer than 15 persons present) and all large establishments. In Scotland the basic sample was drawn from the 1964/65 Valuation Roll. A test was held in April 1964, involving around 1,700 households in some 22 areas across Scotland, to evaluate the proposed sampling method. The sample was then updated from a list of new dwellings up to February 1966 (census day in Scotland was 23 April) supplied by local valuation assessors, and from information on recently occupied accommodation provided by town and county clerks.

The Special Study areas, covering the counties of Roxburgh, Sutherland and Zetland, together with Lewis and Harris, Fort William and a surrounding area, and Livingston New Town and its surrounds, were selected for a full enumeration since more detailed information was needed for special economic and planning studies. Data from the 100 per cent count for these areas was then sampled from a list of addresses selected in the same way as for all other areas in Scotland, to produce consistent statistics.

The number of questions was slightly greater than on the 1961 long form. There were three entirely new topics (cars and garaging, means of transport to work and additional employment) and the questions on a number of regular topics sought more detailed information, in particular exact date of birth (rather than age at last birthday), usual residence five years before the census (in addition to the one-year question), town and county of usual address of mother at the time of birth (rather than just the country), economic activity in the year preceding the census (as well as during the preceding week), and all degrees, diplomas and vocational qualifications (as well as professional qualifications). The use of a ‘fixed shower’ replaced the ‘cold-water tap’ in the amenities question, and a distinction was made between those WCs with an entrance within the building and those with an entrance outside the building in the garden, backyard, or lane. The questions about fertility, nationality and use of the Gaelic language were dropped.

The 1971 Census and the Income Question

The plans for the 1971 Census were the most ambitious yet. The development of computer processing unlocked significant increases in the volume and detail of output. Because of public concern about the privacy of data held on computer, the British Computer Society (BCS) offered to carry out an independent review of IT arrangements shortly after the 1971 Census. This was accepted and the BCS was invited back to carry out similar reviews before the 1981 and 1991 Censuses.

The methods of collecting the information were reviewed with the aim of improving the quality of the results. Two important steps had to be taken. Firstly, the workloads for field staff had to be reduced. Secondly, better instructions and training had to be given to the people doing the job. Reducing workload could only mean employing more people, particularly since the size of the task was greater than in 1961 because of a larger population, more households and yet more questions. The census field force in Scotland had hitherto been based on the registration service but it was clear that this would not cope with the extra demands. So a new census supervisory structure was created, with 4 Field Liaison Officers, about 400 Census Officers and a similar number of Assistant Census Officers, and 14,300 Enumerators.

The 1971 Census form was larger in both format and content than in any other previous census. A new question on parents’ country of birth was included and, although no information was sought on nationality, people born overseas were asked their year of first entry into the UK. The question on address five years ago, first asked in the sample 1966 Census, was included in a full census for the first time to improve migration estimation. New information was collected on the dates of birth of all children born alive to women aged under 60, aimed at providing data on trends in family size and spacing.

An attempt was made to identify structurally-separate dwellings by asking if the household shared any room, hall, passage or staircase with another. This enabled the first attempt to classify households according to the degree of sharing with other households – a task which remains notoriously difficult.

A question on income was considered for inclusion for the first time in the 1971 Census and was a major feature of the preparatory tests in 1968 and 1969. But response rates among those households receiving an income question was poor. A follow-up found that a fifth of householders who had refused to complete a form with the income question on it specifically cited the inclusion of the income question as the reason for refusal. And there was evidence of resentment and objection to the question from letters to the Registrar General and MPs, as well as adverse publicity in the press. So the question was dropped, partly to avoid the danger of undermining the overall response rate and partly because there were strong grounds to suspect the accuracy of the replies. Instead, a voluntary sample survey of incomes was held in 1972 as a follow-up to the census. This was not completely successful either, and only achieved a response rate of 43 per cent – much lower than for other government social surveys.

Three improvements were made in enumeration which had a wider effect on the outputs of the census. First, enumerators transcribed some basic information onto sheets for optical mark reading directly by the computer. This was the first use of such technology in the census and provided the data for a set of innovative preliminary tables, before the main results were ready for release. Second, the census districts on which the enumeration was arranged were for the first time based on local authority areas rather than registration districts. Third, enumerators were issued with Ordnance Survey maps of their enumeration districts (rather than a tracing of the boundary and description of the district as in earlier censuses) which allowed them to reference properties precisely on the National Grid. That paved the way for one of the most significant developments in the analysis of census outputs – the study of small area statistics. Although some small area data had been produced from the 1961 Census, consultation with users and extensive trialling in 1968-69 led to the decision that the National Grid should be used as an alternative output geography. So data from the census (and from the next census, in 1981) was made available for each 1 kilometre grid square. The resulting maps, published in an atlas entitled People in Britain, were made possible by developments in computer processing and gave a new view of the spatial distribution of the population which made census data accessible to a wider public and, in particular, to schools and colleges.

The 1981 Census and technological advances

The 1981 Census was the first to be heralded by a White Paper announcing the government’s proposals for the census (although a White Paper had been published about the short lived plans for a mid-term census in 1976, which were abandoned for financial reasons).

Preparations for the 1981 Census were carried out against a background of increasing awareness of Scotland’s distinct characteristics and needs, evidenced by the passage of the Scotland Act 1978 which paved the way for legislative devolution - although these plans were abandoned after gaining insufficient support in a referendum in 1979 A significant number of uniquely Scottish questions were considered for inclusion in the questionnaire. Though some were dropped before the final version, there was still a greater number of differences than in the past between the Scottish questionnaire and the one used south of the border (the Welsh version only differing from its English equivalent through the inclusion of a question on Welsh language). The appearance of the questionnaire, too, was notably different from the English and Welsh versions

As was the case in the first Scottish census 120 years before, the main variations related to housing, where the Scottish questionnaire was designed to provide finer detail about the characteristics of the housing stock and on densities of occupation. For example, in England and Wales the enumerators were asked to record the household’s accommodation in one of five categories of building/structure type while in Scotland there were nine categories. The Scottish questionnaire also sought extra information on the floor level of the household’s accommodation, the number of rooms and shared access.

By contrast, the questions about household members were almost identical across Great Britain, though the Scottish questionnaire continued the Gaelic language question and chose not to distinguish between ‘married’ and ‘re-married’. After the 1971 Census, it had become evident that the term ‘head of household’ was contentious where the husband and wife regarded themselves as joint heads, and was not appropriate in households where several unrelated adults shared the accommodation on equal terms. In the 1981 Census, therefore, the responsibility for completing the form was placed on each head or joint head (or on all members of the household aged 16 or over where there was no head).

Improvements were made in the field operation, including the identification of areas likely to be difficult to enumerate, efforts to recruit unemployed people as field staff and a centralised payroll computer system. To improve confidentiality, greater care was taken to assign enumerators to areas where they were not known, minimising the risk of enumerating people with whom they were personally acquainted. This was diametrically opposite to the view taken in the Rickman censuses that an intimate knowledge of an area was an essential requirement for the enumerator.

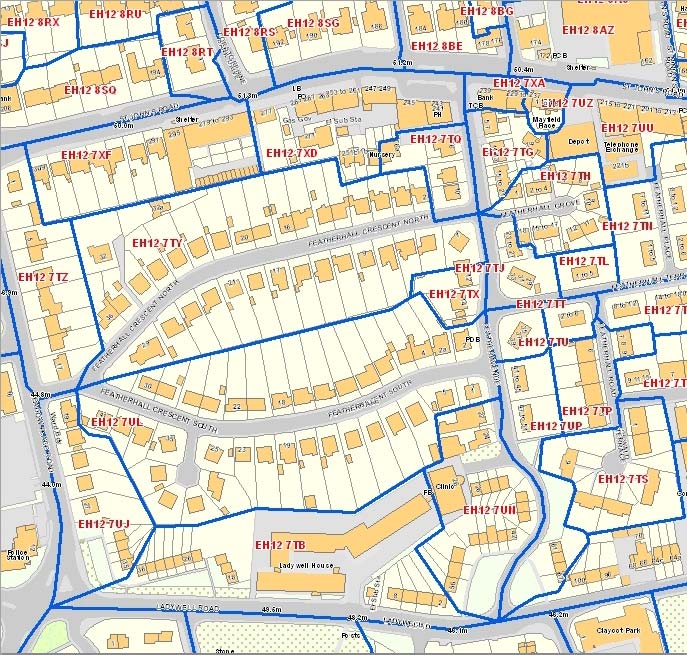

But the biggest change in the fieldwork was the geographic work underlying it. In 1973, the General Register Office for Scotland decided to map and maintain boundaries containing the addresses in each postcode area across the whole of Scotland. The postcode was used in two ways in 1981: enumerator workloads were created by assembling postcodes into suitably sized areas and published statistics for enumeration and other areas were based on an aggregation of information about postcode areas. This policy was unique to Scotland in 1981 and made it easier for enumerators, and users of census outputs, to relate the enumeration and output areas to actual groups of households. It was developed further in each subsequent Scottish census.

To avoid the negative comment about the proposed income question in the 1971 Census, and amidst increasing public concern about privacy, a good deal more attention was given to publicity and to public relations generally. Interest was shown by both national and local media, and coverage was especially good on Radio 4, with interviews and discussions on a variety of programmes including the Today programme, Woman’s Hour and the satirical Week Ending.

The 1961 Census had been the first to use a computer to process the census data. But the 1981 Census was the first to fully exploit the power of a mainframe computer to carry out innovative and sophisticated automated editing. During the 1970s, the General Register Office for Scotland installed its own mainframe computer and data entry system to speed up the collection of data from the registration of births, deaths and marriages, and improve the range and quality of population statistics. This new computer capacity, coupled with the variations that had been introduced in the questionnaire, led to a decision that the data from all Scottish questionnaires should be coded and captured in Scotland. The data from the uniquely Scottish questions were then edited manually and on computer in Scotland. Incorrectly captured data, missing values and inconsistencies between data items were corrected using rules programmed into the computer and by employing a ‘hot deck’ method of imputation which created a matrix of values from recently processed, and therefore geographically close, complete and consistent records and imputing these ‘correct’ values into records where items were missing or inconsistent. Meantime, the data common to questionnaires throughout Great Britain were edited by a system developed by the Office for Population Censuses and Surveys. Once the complete set of data for Great Britain had been cleaned and made consistent, a copy of the Scottish data was sent back north of the border for the production of statistical tables.

This so-called ‘Scottish Data System’ was a significant development for the embryonic IT department of the General Register Office for Scotland, and the number of expert staff employed by the organisation increased accordingly, along with the purchase of a second, more powerful, mainframe computer that was dedicated to the census. Before the days of high-speed telecommunications, successful operation relied on the physical transfer of data on multiple reel-to-reel 9 track magnetic tapes and vast quantities of computer printout. These arrangements worked despite coinciding with nationwide industrial action by civil servants.

The 1991 Census and the ethnic group question

From an enumeration, data processing and statistical output production point of view the 1981 Census was generally regarded as highly successful. However, there were a number of logistical and data consistency issues that arose through having a separately developed Scottish Data System in Edinburgh to deal with the comparatively few uniquely Scottish data items and another one, developed and operated by the Office for Population Census and Surveys, which dealt with the considerably larger number of common data items. Similar consistency issues arose around the production of statistical tables and their interpretation by users. So in the early planning for the 1991 Census, there was a general agreement that for reasons of efficiency, consistency and economy there should be as few differences between the questionnaires as possible. This in turn led to a decision to create common data capture, processing and output production systems that would handle questionnaires from Scotland, Wales and England.

There was one big change in the question set for 1991 - the inclusion of an ethnic group question in a British census for the first time, after careful testing to find a broadly-acceptable wording and a final trial in 1989 in Berwickshire, East Lothian and Edinburgh (as well as in Birmingham, Wandsworth and Merton, and Scarborough in England). It proved to be one of the major successes in the 1991 Census and its inclusion provided information of immense value throughout the subsequent decade. Other new topics covered limiting long-term illness, central heating and a question about the term-time address of students.

The postcode of enumeration address was captured from the questionnaire and entered on the database for the first time, despite opposition from some by MPs who feared that the information would be used for directing mail shots and identifying high risk areas for insurance and mortgage purposes. The question on hours worked was reinstated, having been omitted in 1981. For the first time, an attempt was made to collect information from wholly absent households, albeit on a voluntary basis, by asking householders to complete a form on their return home. For those households noted as absent by the enumerator that did not subsequently return a form, the processing system used imputation methods to create a full set of household and personal data.

Also for the first time in the census, microdata was made available to users in the form of two Samples of Anonymised Records. Known more commonly in other counties as Public Use Samples, these SARs complemented the traditional tabular output of aggregated statistics by providing abstracts of individual records with names and other identifiers removed.

Recognising the increasing difficulty in contacting households, the Census Offices retained the services of an advertising agency to heighten public awareness. The main element of the resulting publicity campaign was an award-winning 30 second television commercial featuring a talking baby, inspired by a then current John Travolta movie. This was supplemented by a 10 second advert using an animated version of the census logo, with its slogan "It counts because you count". The successful campaign did much to counter the increasing hostility towards the census created by public resistance, especially in Scotland, to the government’s ‘community charge’ (or poll tax, as its opponents called it). Despite these efforts, however, non-response to the 1991 Census, estimated to have been around 2.2 per cent for Great Britain, was the highest yet recorded.

The robustness of the 1920 Census Act has already been noted. But, for the 1991 Census, a new Act had to be hastily drafted to close a loophole that had been created by the repeal in 1989 of parts of the 1911 Official Secrets Act, including the provision which safeguarded personal information after the census had been taken. The Census (Confidentiality) Act 1991 was passed only a few weeks before census day and created an offence of unlawful disclosure of personal census information as well as extending the previous confidentiality provisions to include post-enumeration census-related surveys and to encompass any person employed for the purpose of taking the census.

Most censuses have their own particular crisis. For the 1991 Census, it was undoubtedly the student problem. A routine audit check noted that more people than expected were being imputed as students. This was the result of the new question about students’ term-time address, introduced late in the programme when it was realised that the census would be conducted in vacation time for many universities. It had been anticipated that there would be some inconsistencies between the new question and the regular question about economic activity in the week before the census. In the event, many non-students answered the new question in error, thereby inflating the number of 'students' recorded. By the time the error was spotted, an estimated 400,000 people had been misclassified, and the input database had to be corrected. Fortunately, data had been copied from the mainframe database at various stages, to be held in reserve as a contingency against any such problems occurring. Although the census outputs were delayed by some six months, this precaution averted a major disaster.

But before then, in 1990, the General Register Office for Scotland had averted another potential disaster. Contractors were putting a new surface on the roof of the census office at Ladywell House in Edinburgh when their boiler of hot tar blew over and ignited the whole length of the roof. Immediately below, staff were mapping the Scottish enumeration districts. Most of the maps were fortunately stored in metal chests and survived both the fire and the vast quantities of water not only from the firemen’s hoses but also, during the following days, from torrential rain pouring through the hole in the roof. The only effect was a delay in planning the enumeration districts.

Flooding not only affected the mapping at Ladywell House, but plagued the refurbishment of the building at Hillington near Glasgow, which had been chosen to process most of the census forms for the whole of Britain. The building, the size of three football pitches, had been a Rolls Royce factory which during the Second World War had manufactured Merlin engines for Spitfires. Fortunately, the start of the coding operation was not delayed, but flooding recurred during the processing when seagull nests blocked the gutters.

| Before the hole in the roof was fixed……. | ………….. and afterwards |

|---|---|

|

|

After the success of using postcodes in 1981, and the emergence of suitable technology, the General Register Office for Scotland made a pioneering decision to digitise the boundaries of all postcode boundaries in Scotland (130,000 postcodes from 5,500 maps). Enumeration districts were planned from scratch to bring workloads up to the level of those in England and Wales. To meet user demands for continuity with outputs produced in 1971 and 1981, and also allow greater flexibility for aggregation to ad-hoc output areas, the General Register Office for Scotland introduced a new form of ‘output area’ (OA), each designed to exceed a minimum threshold for population size. This was achieved using actual household and resident counts, the digitised postcode boundaries and geographic information system techniques.

Local statistics for small areas had increased in volume and complexity considerably over the years. In 1991, there was an expansion of output into two separate but related tiers called local based statistics and small area statistics. A data modification technique called Barnardisation (or blurring) was used to ensure that no information in the tables could be related to any identifiable person or household with any degree of certainty. However, this approach was later criticised by census users because it had a distorting effect, especially on table totals and for areas created by aggregating small areas into larger areas.

The 2001 Census – the bicentennial census

The 2001 Census in Scotland was the first to be approved by the devolved Scottish Parliament created in 1999, rather than by the Westminster Parliament. The Scottish Parliament, like its counterpart in London, insisted on an important change to the question set – the inclusion of a voluntary question about religion. Since the 1920 Census Act envisaged that all questions would be compulsory, this required fresh primary legislation – the Census (Amendment) (Scotland) Act 2000. In the Scottish census, two questions about religion were included, asking about religion of upbringing and current religion, whereas in England and Wales only the latter question was asked. This was the first question about religion to be included in the census since 1851, and there was a race to complete the passage of the new Act through the Scottish Parliament in time for preparations to be finalised.

Other new questions were asked about general health, the provision of unpaid care, time since last paid employment, the size of workforce at place of work and supervision of employees. The answer categories in some questions, such as ethnic group, were updated. And all the questions included in the 1991 Census were asked again in 2001 – except for questions relating to usual address and whereabouts on census night.

A new approach was taken to the return of the census forms by the householder. Instead of enumerators collecting all the completed forms, householders were given the option of posting them back. This allowed a smaller number of enumerators to be employed and was a popular innovation, with 91 per cent of forms posted back. It was particularly important because an outbreak of foot and mouth disease among farm animals made it difficult for enumerators to visit households in rural areas for fear of spreading the infection.

The return of questionnaires by post was one of four key tasks outsourced to the private sector for the first time. Contractors were also responsible for paying the small army of nearly 9,000 field staff and for running a call centre to answer questions on the telephone. A fourth, and major, contract covered the printing of about 3 million scannable questionnaires, the capture and coding of the information on the completed questionnaires, the creation of microfilm from the scanned images and the destruction of the paper questionnaires This made it easier to take advantage of modern developments in scanning and optical mark and character recognition, with efficiency improvements, and enabled all the data on the census questionnaires to be coded and captured rather than taking a 10 per cent sample of the replies to the less frequently-used topics. The questionnaires were turned into shredded bales of paper which were pulped and used to manufacture toilet rolls, saving about 2,000 mature trees. For the first time, the paper returns were not kept for archival purposes, with microfilm serving as the physical archive.

The biggest innovations came with the publication of the statistics. The 2001 Census results covered the whole population rather than omitting people who were not recorded on the household forms and people in households which the enumerators failed to locate - which was estimated to have been 1.9 per cent of the population in 1991. A new approach – christened the One Number Census - allowed these groups to be identified by a follow-up survey and added to the census results. A new method of filling data gaps - called donor imputation - was used in 2001. The census database searched for a similar person or household and the values were copied into the records with the missing data items. The confidentiality protection measures for outputs were improved to meet the competing demands for more protection for smaller areas, wider dissemination of results and a richer and more usable dataset - and to overcome the anomalies in the output previously created by Barnardisation. Records of households and communal establishment residents were swapped with similar records in the same area and the minimum number of households in an OA was increased.

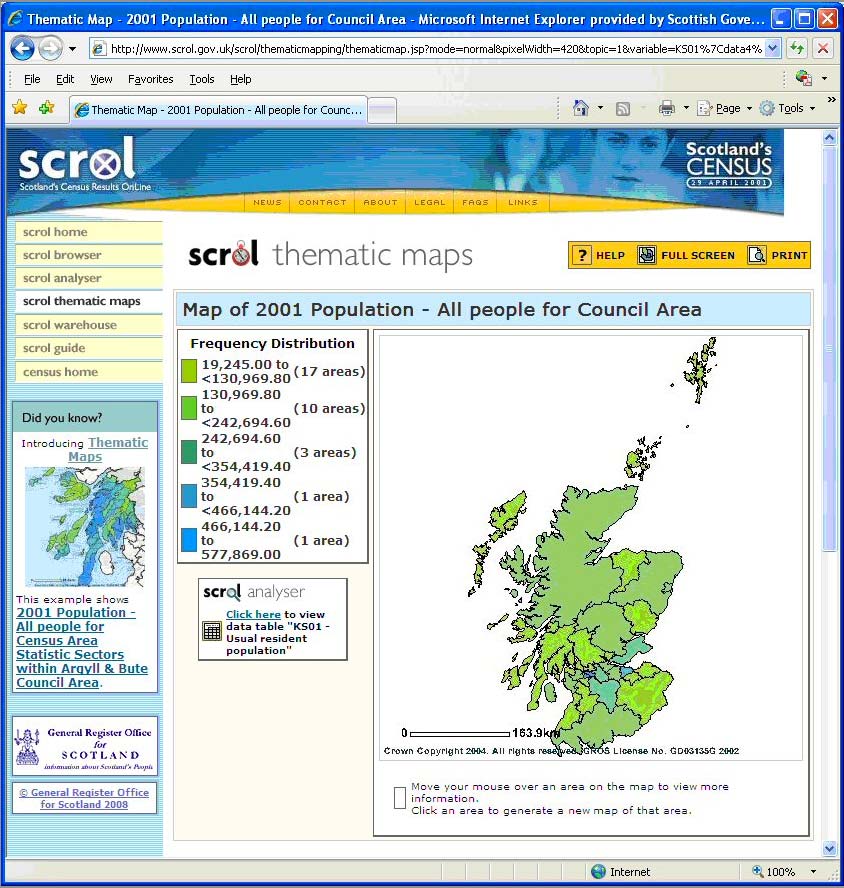

For the first time, the bulk of the results were made available free of charge on the internet, through a website entitled Scotland’s Census Results Online (SCROL). The aim of the SCROL website was to improve the use of, and access to, census statistics using visualisation and analysis tools to help the user understand and interpret the results. Production and dissemination of tabular outputs was significantly improved and simplified by powerful and easy to use table production software called Supercross. This enabled the General Register Office for Scotland to publish outputs much faster than before: most of the results from the 2001 Census were made available in March 2003.

The use of the One Number Census methodology meant that the results of the 2001 Census covered the entire population of Scotland and were believed to be the most complete and reliable results obtained by any census in Scotland. They showed that the population was 5,062,011, a little over three times the size of the population at the first statutory census in 1801.