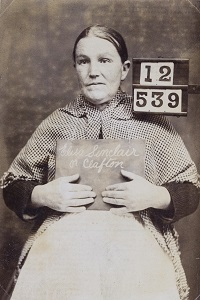

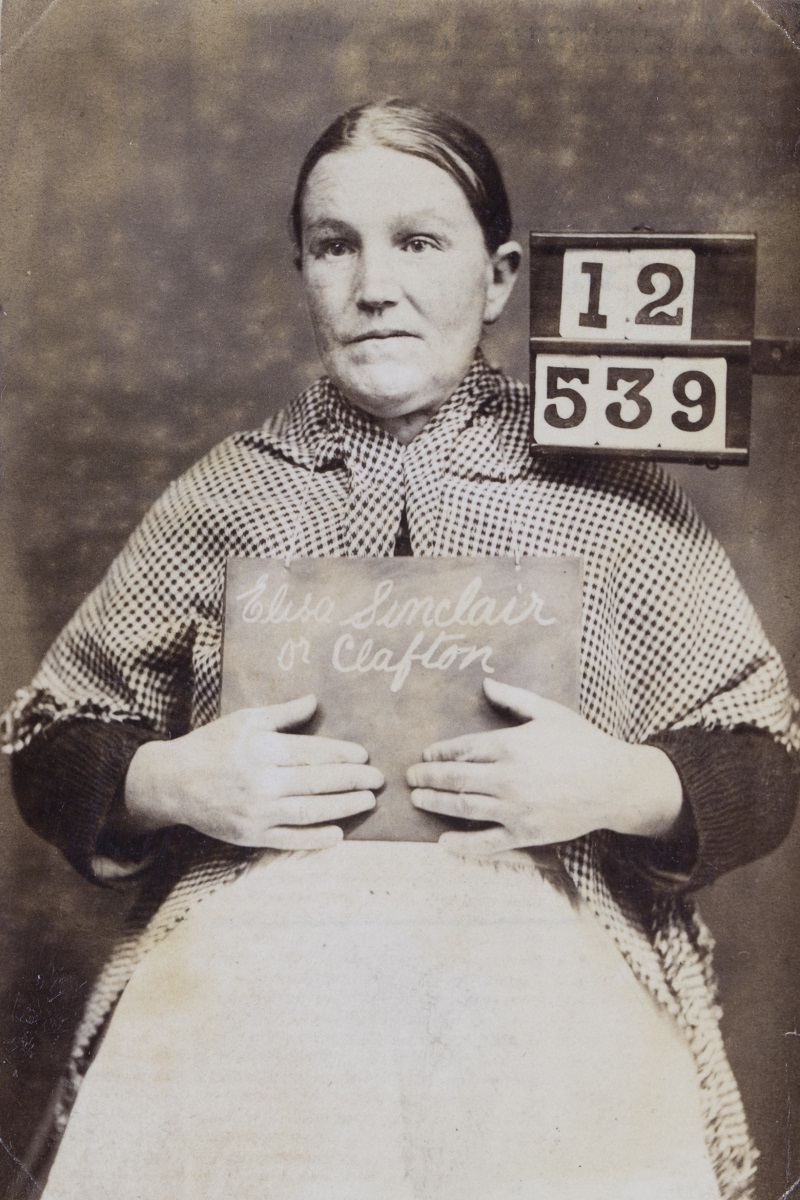

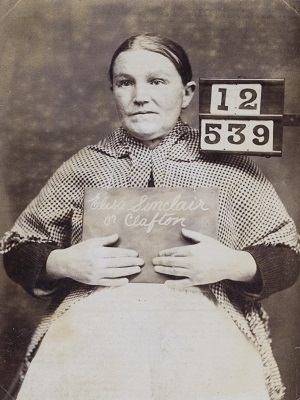

Elizabeth (Eliza) Sinclair or Clafton

Admitted 1871. Murder

In March 1871, 25-year-old Eliza cut her own throat at the family home in Stow (Midlothian) then spontaneously did the same to her daughter Isabella (11 months) and son Daniel (three years). Eliza lived, the children did not. Found guilty but insane before the High Court of Justiciary, she was committed to Perth Criminal Lunatic Department (CLD) 'until Her Majesty's pleasure shall be known'.

Neighbours of long acquaintance who gave supportive testimony said Eliza was a good wife and mother, but a fragile person, with low resilience. 'If any person did anything to the prisoner to offend her she took it very much to heart & became very dull & quiet'.

Thus when accused of stealing from a local grocer by the owner's daughter, Christina White, Eliza fell apart. For their part, medical men thought the underlying cause was lactation and possibly the psychological impact of physical injury during earlier childbirth.

Clinicians assessed prisoner-patients regularly to see if they could be released, conditionally or unconditionally, carefully monitoring steps towards freedom. Along with Marjory McKeraker and three other female inmates, Eliza had the privilege in August 1880 of walking outside the prison walls for a few hours a week under guard, because they were all 'perfectly sane' and unlikely to relapse without some advance warning.

Eliza was first discharged in 1881. Conditional release was closely monitored by a nominated guardian with whom the prisoner-patient had to live, to prevent any danger to self or public. The Scottish Office paid guardians, but the task was onerous.

Eliza had a mind of her own. By leaving her guardian and associating with her husband and other men, she was readmitted several times for breach of conditions. In August 1882 she gave birth to a son, who was taken from her by the Inspector of the Poor once weaned. She was pregnant again in March 1890 and, unable to work for her living (she tried to throw herself out of a window when the officers came to collect her), recommitted. Her baby girl was removed from her in April 1891.

Eliza's case history makes her sound rootless and irresponsible, but her life was typical of working-class people in Victorian times: employment could not be guaranteed and poverty was an ever-present threat; geographical mobility was normal and frequent; and personal relationships could be dissolved easily by the acid of poverty. She herself was illegitimate, her father a married man, her mother then an unwed servant. Eliza married the weaver Samuel Clafton in spring 1864, who used the name John Smith in an effort to evade a paternity suit in Yorkshire. Footloose and unreliable, he was regarded as quite unsuitable to act as her guardian.

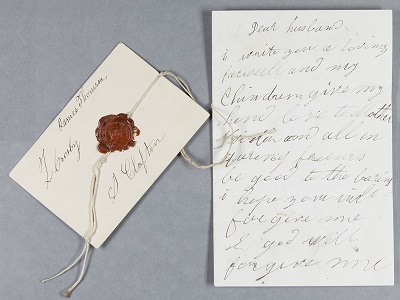

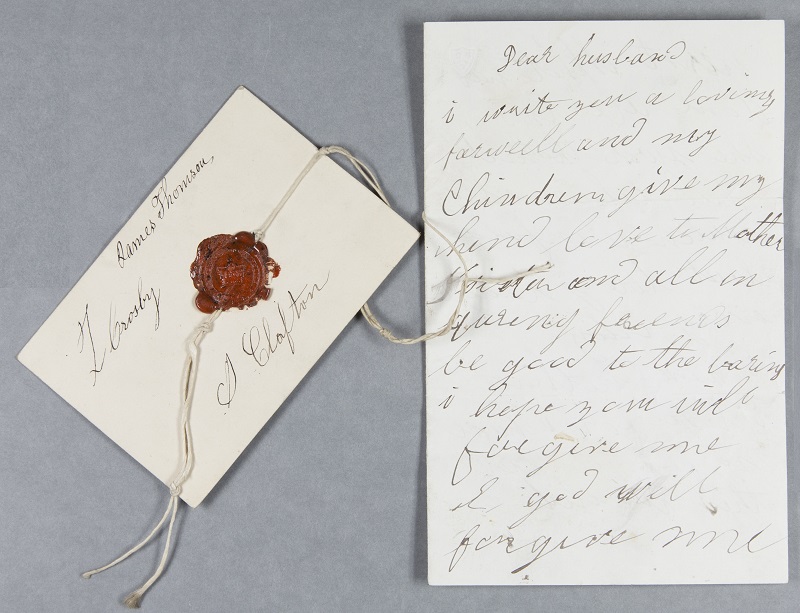

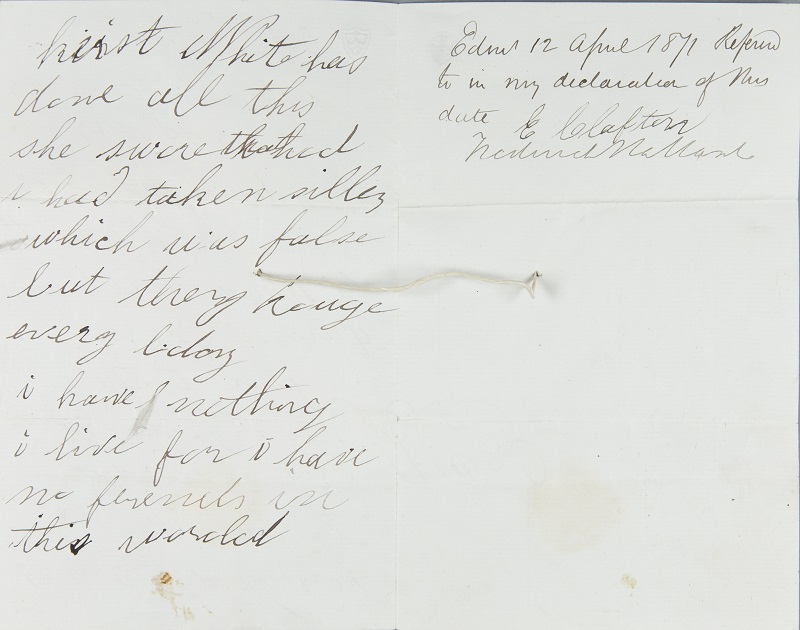

If the description of the murder and its aftermath in the trial documents and newspapers is harrowing, Eliza's redundant suicide note is even more deeply affecting.

'Dear Husband. I write you a loving farewell, and my children, give my kind love to mother sister and all inquiring friends be good to the bairns, I hope you will forgive me and God will forgive me, Kirst White has done all this. She swore that I had taken siller [money], which is false, but they hang every body. I have nothing to live for; I have no friends in this world.'

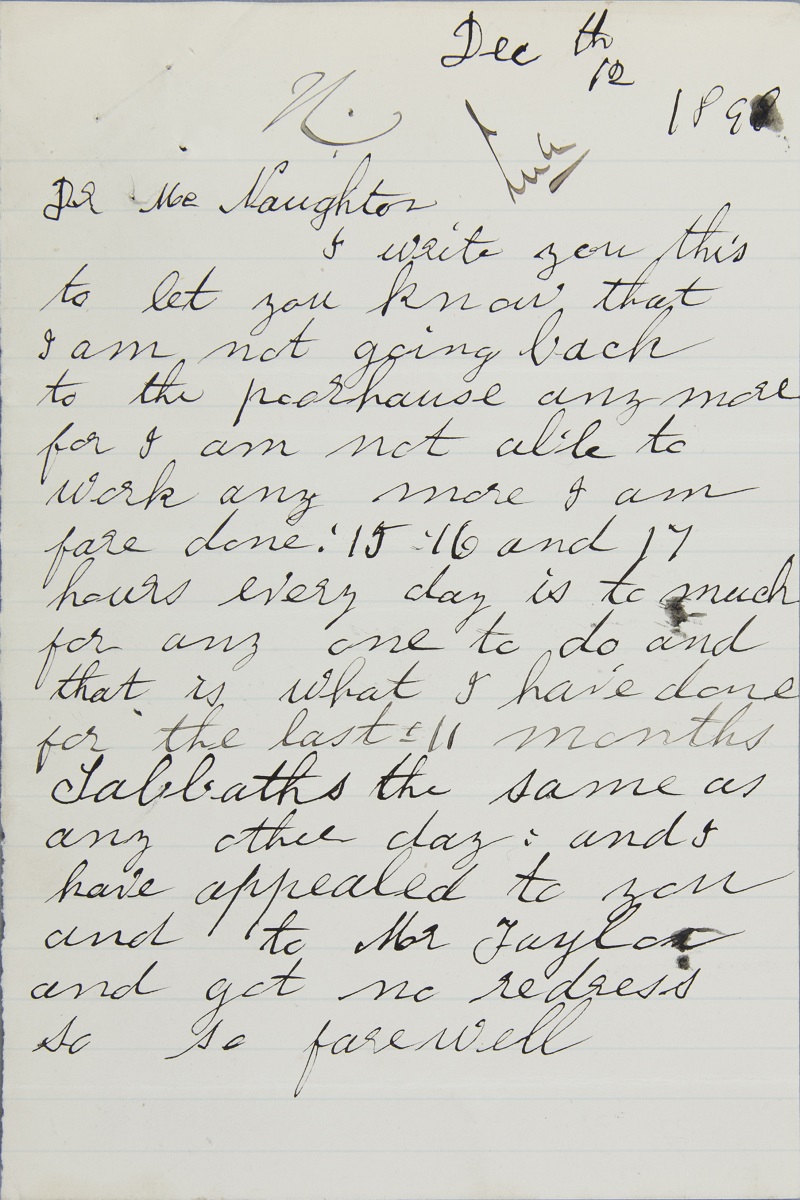

No longer insane, Eliza was removed to Dysart poorhouse in December 1897 because she was unable to support herself. Days later, she drowned herself in the River Leven.

Photograph of Eliza taken from the Criminal Lunatic Department Case Book

Credit: Crown copyright, NRS, HH21/48/1 page 393

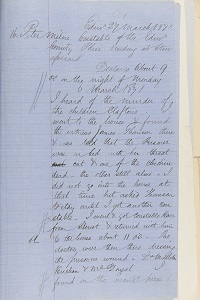

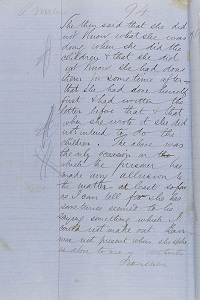

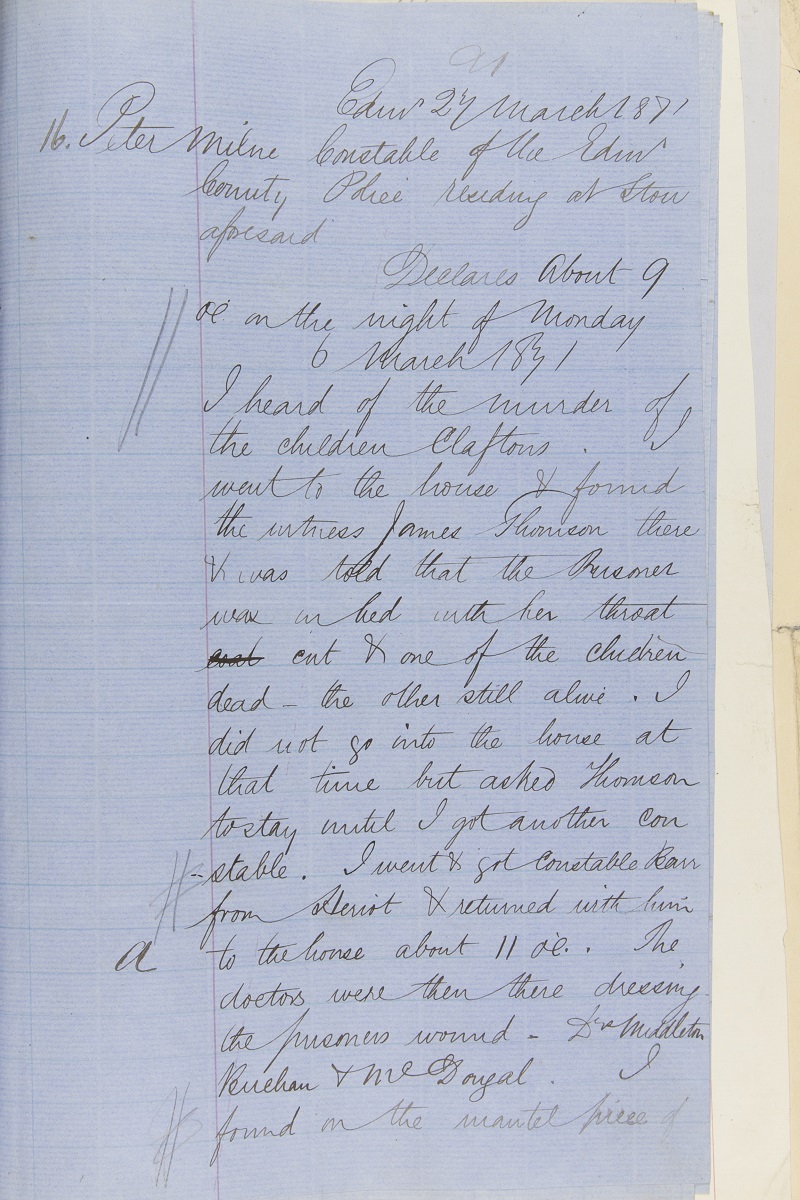

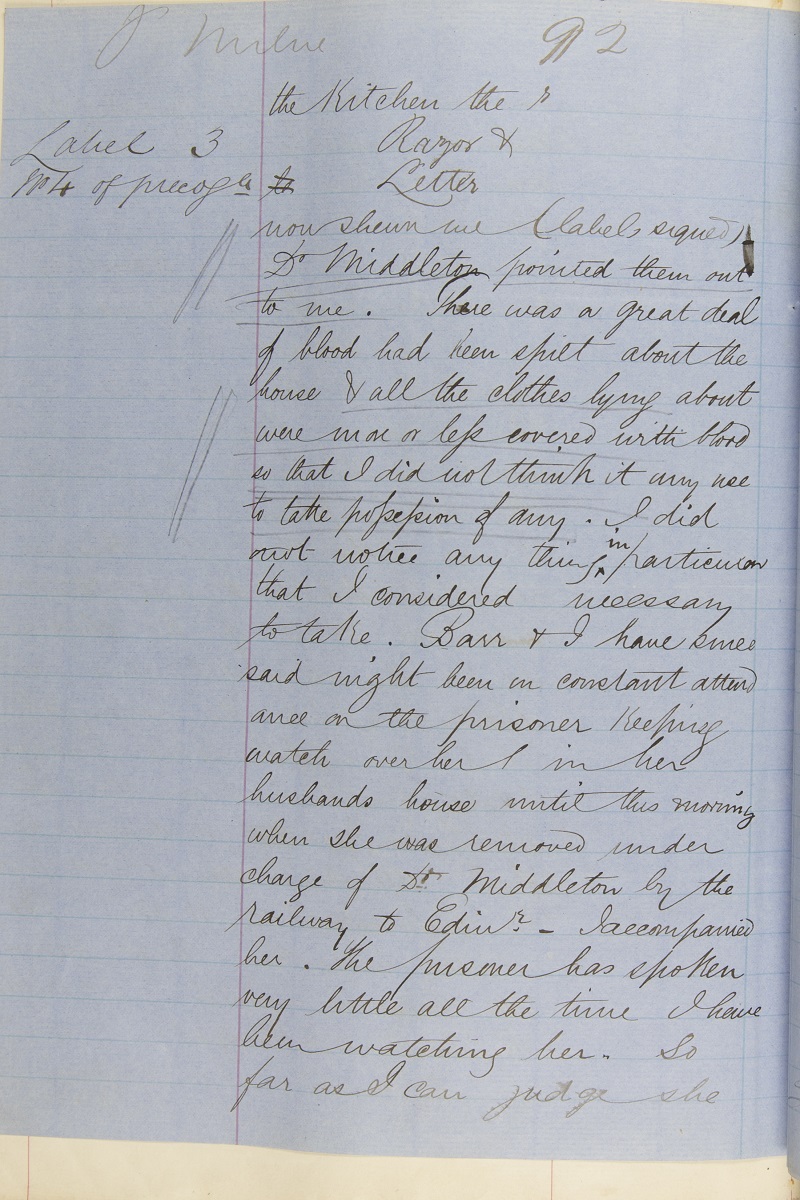

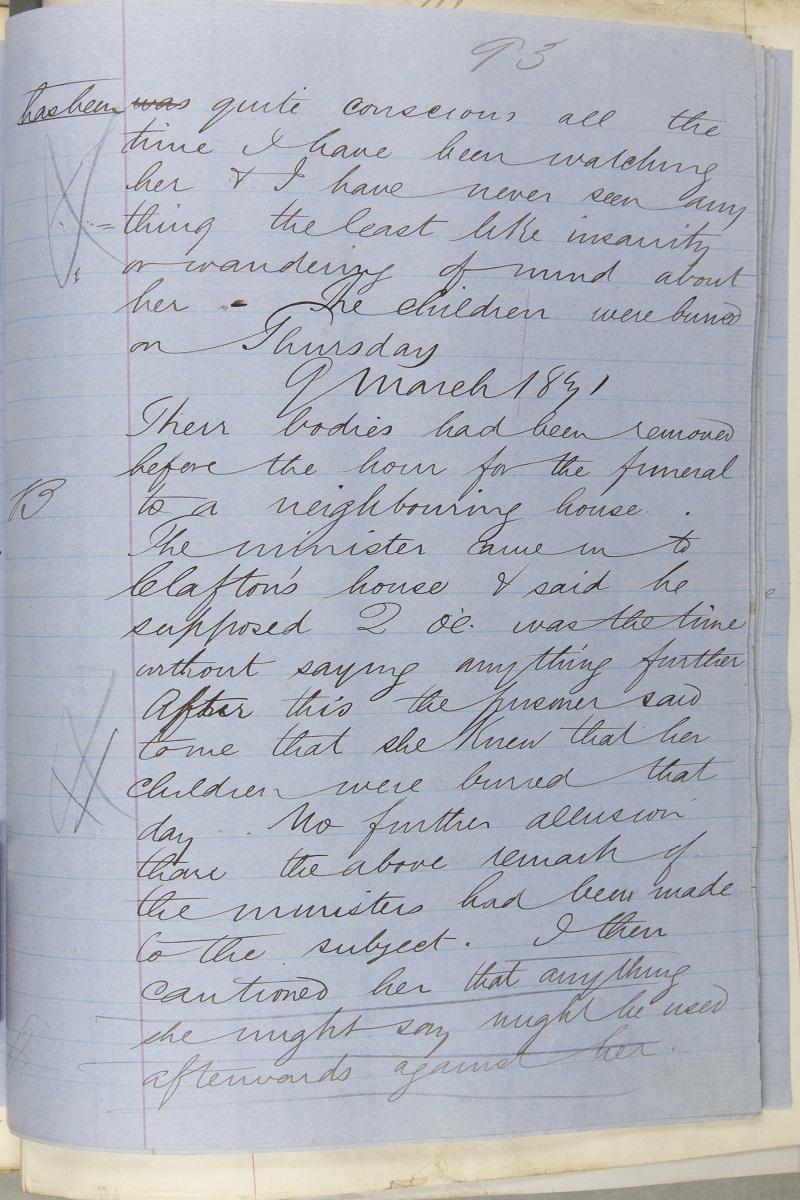

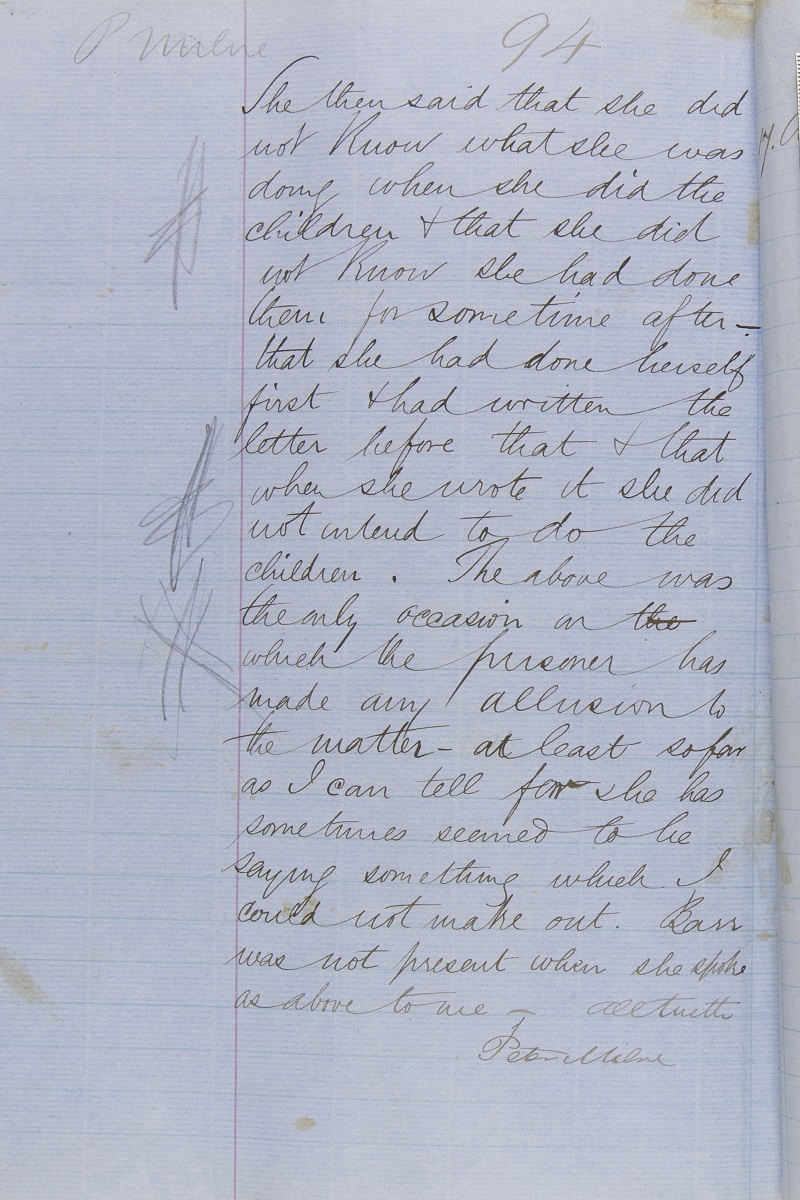

Evidence from Peter Milne, Constable of Edinburgh County Police, 27th March 1871. This record is from the precognition file for Eliza’s trial where facts were gathered into the murder of her two children, p1

Credit: Crown copyright, NRS, AD14/71/295

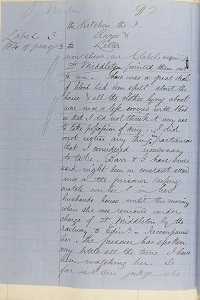

Evidence from Peter Milne, Constable of Edinburgh County Police, 27th March 1871 . This record is from the precognition file for Eliza’s trial where facts were gathered into the murder of her two children, p2

Credit: Crown copyright, NRS, AD14/71/295

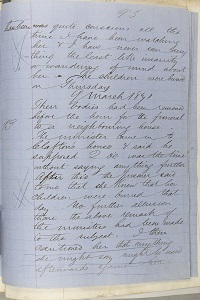

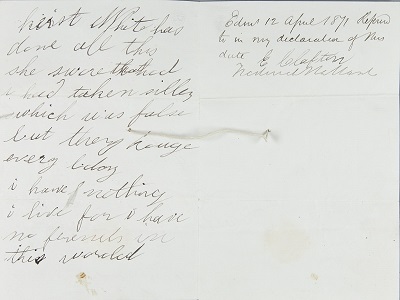

Evidence from Peter Milne, Constable of Edinburgh County Police, 27th March 1871 . This record is from the precognition file for Eliza’s trial where facts were gathered into the murder of her two children, p3

Credit: Crown copyright, NRS, AD14/71/295

Evidence from Peter Milne, Constable of Edinburgh County Police, 27th March 1871 . This record is from the precognition file for Eliza’s trial where facts were gathered into the murder of her two children, p4

Credit: Crown copyright, NRS, AD14/71/295

Eliza’s suicide note used in evidence in her trial, 1871, p1

Credit: NRS, JC26/1871/307

Eliza’s suicide note used in evidence in her trial, 1871, p2

Credit: NRS, JC26/1871/307

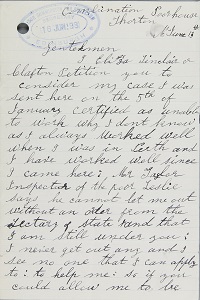

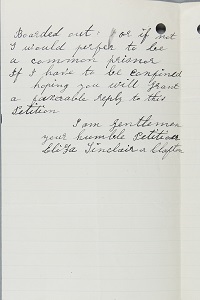

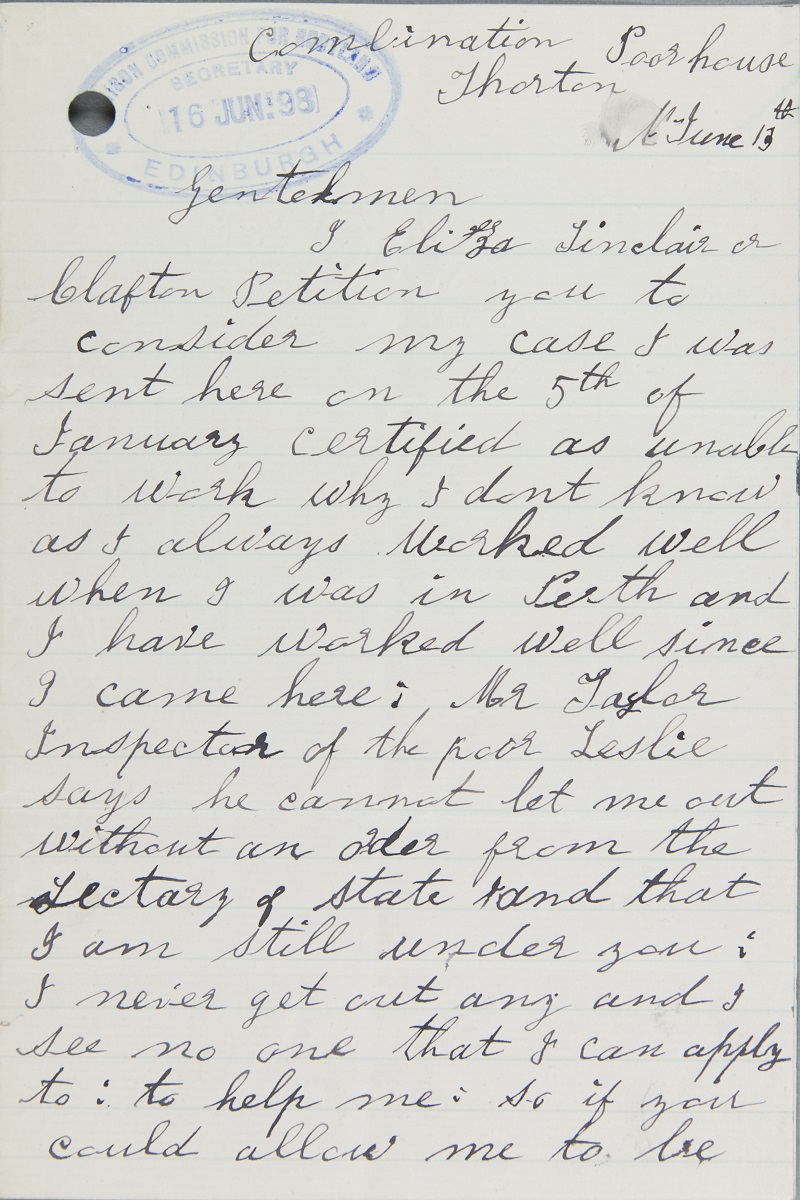

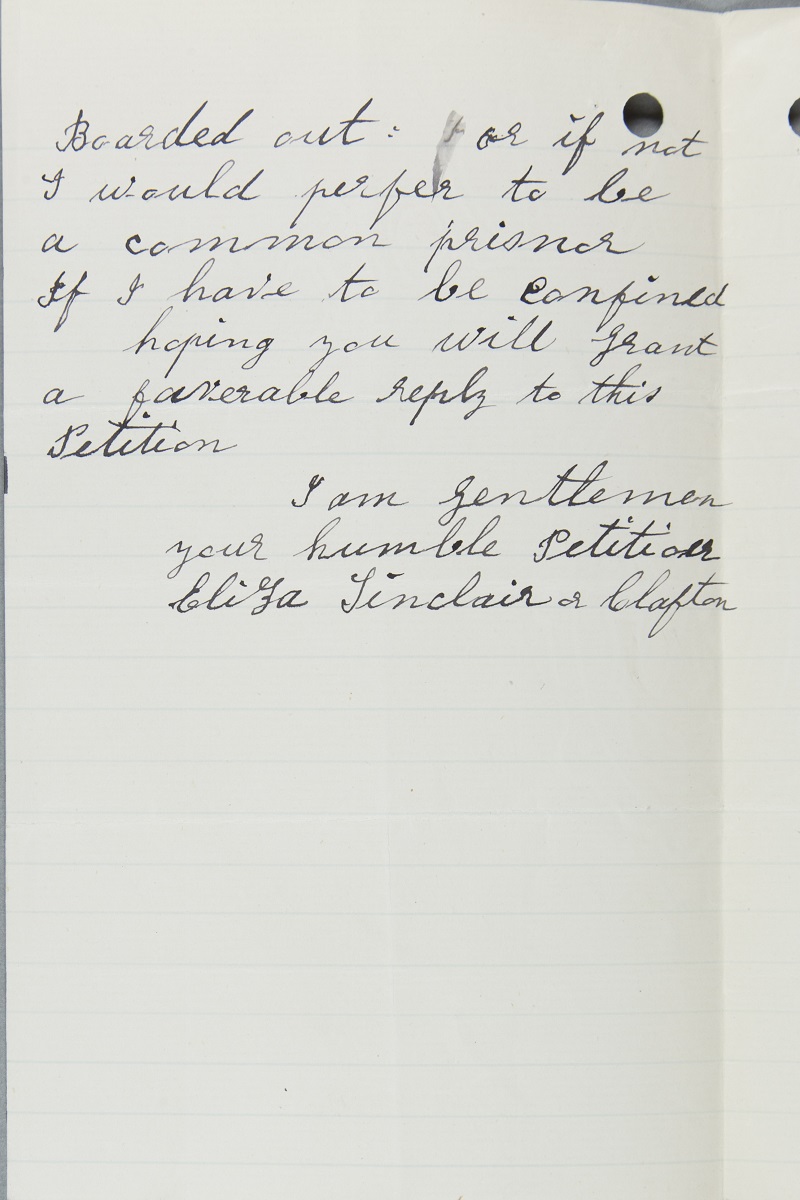

Eliza writes to the Prison Commissioners asking for a letter to say that they are responsible for her so she can be released from the poorhouse. She states that she would rather be ‘a common prisoner if I have to be confined’, 13 June 1898, p1

Credit: NRS, HH17/23

Eliza writes to the Prison Commissioners asking for a letter to say that they are responsible for her so she can be released from the poorhouse. She states that she would rather be ‘a common prisoner if I have to be confined’, 13 June 1898, p2

Credit: NRS, HH17/23

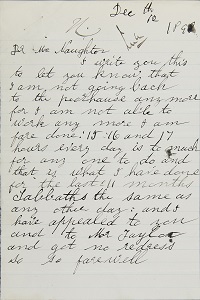

Letter from Eliza to Dr McNaughton telling him that she refuses to return to the poorhouse and work up to 17 hours a day – she is ‘fare done’, 12 December 1898

Credit: NRS, HH17/23

Eliza Sinclair or Clafton. Declaration, 12 April 1871 (NRS, AD14/71/295). Voices: Jade Anderson and Craig Smillie

Eliza Sinclair or Clafton. Petition to H.M. Prison Commissioners, 10 June 1887 (NRS, HH17/23). Voices: Jade Anderson and Craig Smillie

Eliza Sinclair or Clafton. Jane Crombie’s statement, 17 June 1871 (NRS, AD14/71/295). Voices: Mia Colquhoun and Craig Smillie

Eliza Sinclair or Clafton. Eliza’s husband, Samuel Clafton’s statement, 14 March 1871 (NRS, AD14/71/295). Voices: Jonathan Craig and Craig Smillie

Eliza Sinclair or Clafton. Suicide note, c. 1871 (NRS, JC26/1871/307). Voices: Jade Anderson