The Development of Scotland's Harbours

The Development of Scotland's Harbours

In 2020, the Scottish Government is celebrating the Year of Coasts and Waters. In this article we delve into our archives to learn more about the development of harbours in Scotland.

Beginnings

Prior to the industrial revolution, fishermen rarely had access to a harbour in the way we imagine today. Fishing boats were small, open, vessels; this style allowed them to be dragged up the beach, on returning with their catch, with the help of the fishermen’s wives and communities, to rest above the tide. Indeed, many fishing villages around the Scottish coast were originally built without any thought of harbours in mind – the main desirable aspect was to have a shingle beach (which provided a firmer base) for bringing up the boats.

As Eric J Graham states, prior to the advent of the railway network in the mid-19th century, 80% of the population of Scotland lived within a mile or two of salt water. During the late Georgian period, the acceleration of the industrial and agrarian ‘revolutions’, prompted local businessmen to increase their access to markets by supporting new harbour developments.

The construction of harbours in Scotland was not an entirely new idea to the industrial revolution. As James R Coull notes, there had been some harbour construction in Scotland from the medieval period which was used both by trading and fishing boats. In Arbroath, for example, the original harbour was built before the Reformation by the abbey in order to promote trade links. Collectors’ quarterly accounts, created by men employed in Customs and Excise and held in National Records of Scotland (NRS) also demonstrate this. One account notes that in the year 1794, the fishing fleet in Ayr was diminishing yet the harbour remained a centre for handling exports of fish caught in the Firth of Clyde and Loch Fyne. An export of 20 barrels of Campbeltown herring to Ireland was recorded.

Why did harbours not flourish around the coast of Scotland from this time? One major factor was the cost of construction as well as maintenance. There was no one single body responsible for building and looking after harbour areas and it often fell to local individuals to fund such projects, such as the Earl of Cromarty who built a harbour in Portmahomack in the late 17th century. In rare cases, fishing communities who desperately needed a harbour, had been known to raise money themselves to finance the construction. One example found in NRS records highlights the case of Newhaven harbour where, in 1860, improvements were overdue. Work was to cost £1600; 75% of this money was granted, with Leith Dock Commission contributing a small donation. The remaining funds were raised by the local community who gave up their whisky for 12 weeks in order to save up the money.

As a result of forthcoming funding, the majority of small fishing communities had to be content with storing their boats on the beach. This was achievable in pleasant weather, but a storm or turn of the tide could sometimes prevent both the launching and beaching of the boat. For men at sea, the sudden arrival of bad weather was a real threat. In many parts of Scotland there was frequently no shelter for miles along the coast. Indeed, Coull notes that ‘in one big storm in 1848, 100 fishermen were lost on the East Coast; in a seven-year period in the 1870s the one community of 300 at Cellardyke lost 30 men; and in the worst ever fishing disaster in the country, 191 men were lost in one day in October, 1881 in South-East Scotland, 129 of them from the one village of Eyemouth.’ NRS records demonstrate that a harbour did not automatically equate safety, however, when it had not been properly fitted with necessary security features, such as lighthouses, fog-horns or basic lighting, without which, the safe entry to a harbour was impossible in bad weather. A Mr Laurence wrote to the Board pleading for help after 11 wrecks had occurred around the harbour of Eday in Orkney, due to a lack of these measures.

A safe place to land

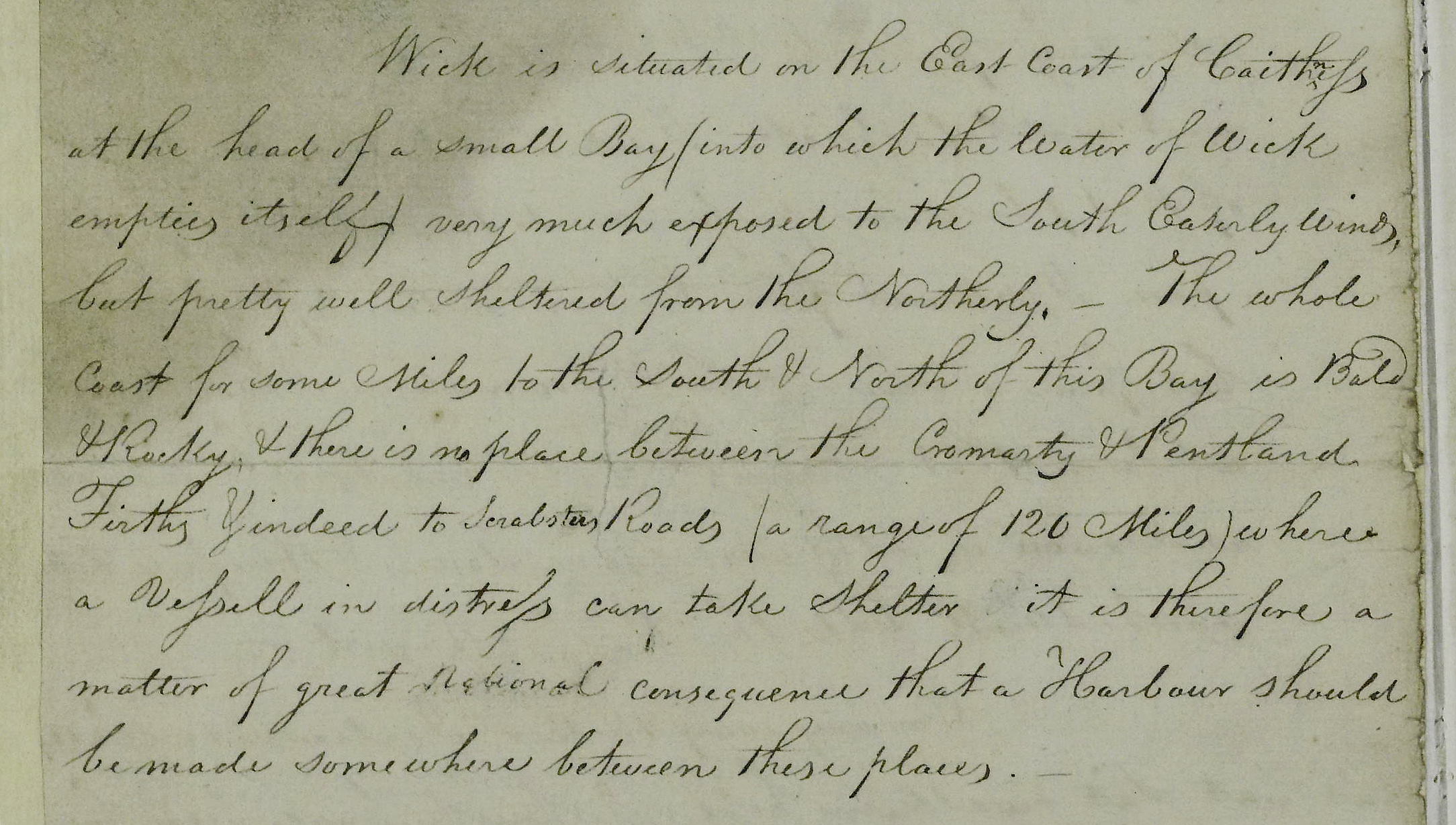

An early example of the 19th century expansion of harbours can be seen in Wick where construction took place from 1803 to 1811. A ‘Report and Estimates for a Harbour at Wick’ had been undertaken by the British Fisheries Society in 1793. It was recorded that 'the whole coast for some miles…of this Bay is Bald and Rocky and there is no place between the Cromarty & Pentland Firth & indeed to Scrabsters Roads (a range of 126 miles) where a vessell in distress can take shelter it is therefore a matter of great national consequence that a Harbour should be made somewhere between these places... I saw no other place where so good a Harbour could be made as at Wick.'

NRS, Records of the British Fisheries Society, GD9/259

Within a few short years of building, however, the harbour became badly overcrowded by boats with the result that in 1824 an extension was authorised. This was an achievement in itself, as even the smallest harbour improvements required an Act of Parliament to proceed. Its success enabled 600 boats to find shelter. Wick was a hive of activity at this time; 11,710 people were involved in fishery there in 1846. Of this number 26% (2,639) were female gutters and 62% (7,269) fishermen and seamen, and even these totals, taken from official records, may understate the true figures.

Pride in these new harbours was felt by the local community and one record in NRS’ archives demonstrates that it was often a source of positivity and cause for celebration. In Newhaven, on 15 April 1876, the foundation stone was laid for the new harbour. A procession took place with local dignitaries in attendance. A stone was laid by Mr Donald R McGregor, MP for the Leith burghs constituency, who also buried a bottle containing that day’s newspaper and a selection of coins in current circulation. His wife had been presented by the women of Newhaven with a doll dressed in a fishwife’s dress with a creel and basket on her back filled with fish.

It was not just the amount of boats requiring access to harbours that encouraged their construction. Throughout the century the style of boats changed. Larger boats, being modified from sail to steam, could no longer be pulled up the beach by the local population and required a safe space for fish to be unloaded and boats to be stored. With the increased size, many vessels required the mouths of harbours to be widened and basins deepened. The Harbours and Passing Tolls Act 1861, allowed loans of public money at low rates of interest with repayments made from harbour dues. These loans were used in facilitating upgrades to the biggest harbours such as Aberdeen, Peterhead and Fraserburgh. The British Fisheries Society was responsible for building villages, harbours and roads to improve the fishing industry. The Fishery Board also took advantage of new technology to create all-tide harbours where ships could enter at any time of day to take shelter from storms.

Plans of proposed improvements to harbours can be seen in NRS’ archives. Many of these have been digitised and can be accessed through the Virtual Volumes system in the Historical Search Room at General Register House, Edinburgh. These range in date and location, for example a plan of Fraserburgh Harbour with proposed improvements, 1838 (RHP45436/1) and proposed works at Eyemouth Harbour in 1960 (RHP40767/1).

Detail from a plan of Fraserburgh Harbour with proposed improvements

NRS, RHP45436/1

In the 18th century the government established the Board of Trustees for Manufacturers and Fisheries. Its duty was to improve the Scottish economy by allocating £6,000 per annum to the development of linen, wool and the fisheries. By the 19th century, the funds provided by the Board could not cover the number of improvements required and were spread so thinly that they benefited no one. Buckie, for example, had the greatest number of fishing boats of any locality in Scotland by the middle of the 19th century. In 1855 it had a total of 849 boats in use and 3,111 fishermen. The Board had wished to transform it to an all-tide harbour but lacked the funds. Work was reduced to purely increasing the depth of the basin of the harbour and could only go ahead when Mr Gordon of Lettfourie contributed £4,000 to the necessary £14,000 total. As time progressed, such was the need for an all-tide harbour that it fell to a local landlord, Mr Gordon of Cluny to build it on a new site at a cost of £50,000. This new harbour could accommodate 400 boats.

The building of the harbour at Dunbar, on the south shore of the Forth in 1840, involved the building of a wharf and sea wall nearly 1,000 feet long and the excavation of over 43,000 cubic yards of material, to enclose a basin four acres in extent. It cost £15,762 of which £4,500 was paid by the burgh of Dunbar, the remainder by the Board.

Aside from providing boats a safe haven during bad weather, harbours were also necessary to enable fish to be landed safely and in fresh condition. The catch could then be transported quickly across the country on the developing railway networks. This also allowed for increased trade and facilitated the expanding maritime trade towards the end of the 19th century. As Kathryn L. Moore demonstrates, Aberdeen ‘was the most important port in the north east and the volume of imports and exports, as well as the number of vessels using the town’s harbour, far exceeded those found at the region’s other ports.’

We’re going to need a bigger boat

In 1909 a change to government policy improved levels of funding. This came at a time when the steam drifter was quickly replacing the sailboat as the main herring fishing vessel. They required deep all-tide harbours alongside various facilities such as bunkering and engine-room stores. Large trawlers were the means for catching cod and haddock and dominated Aberdeen harbour which was the largest fishing port in Scotland and the third largest in Britain. Indeed, the fishing trade at this time was booming with agriculture and fishing accounting for nearly half of male employment in the Highlands.

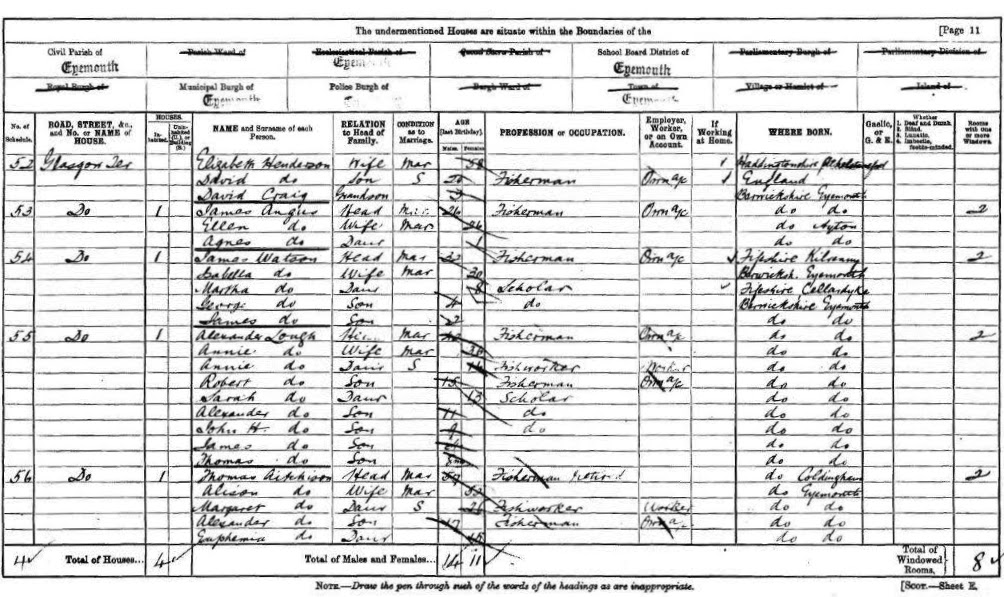

A page from the 1901 census in Eyemouth. The majority of occupations listed relate to the fish trade.

Crown copyright, NRS, 1901 Census, 739/2/10 page 11.

The outbreak of World War One seriously disrupted progress of improvements across Scotland and when peace returned harbour development ‘proceeded in a somewhat stuttering manner.’ Attention became focussed on helping and rejuvenating harbours in places such as Lossiemouth and Eyemouth which had been awarded limited financial support in years prior to the conflict.

In the years following World War Two, the administration of fisheries passed to government agencies. Fisheries entered a new prosperous era with bigger boats and port development. Smaller harbours, such as Alloa, could no longer compete with larger harbours such as Eyemouth and their usage declined.

The Common Fisheries Policy (CFP) of 1970 required that fishermen from within the European Community would be given equal access to all fishing grounds aside from a three mile coastal zone for local fishermen. Sir Con O’Neill, a Foreign Office official, who was heavily involved in the negotiations, later said ‘the question of fisheries was economic peanuts, but political dynamite.’ These policies led to over fishing in British waters and was a disaster for both fish stocks and fishing communities. In harbours where one could once cross the water stepping from ship to ship, they were now used by just a few vessels. A handful of harbours still remain active today in Scotland, such as Peterhead, one of Scotland’s most versatile harbours which welcomes different vessels carrying a variety of produce including fish.

Would you like to find out more about harbours in Scotland? NRS has a wealth of resources for you to investigate. Use our online catalogue to start your search today.

Resources used:

Scottish Local History. Issue 60, Spring 2004

J R Coull, The Sea Fisheries of Scotland, 1996

National Records of Scotland (NRS), Exchequer Records: Customs Records: Collectors' Quarterly Accounts, E504/4/10

NRS, Papers of the Society of Free Fishermen of Newhaven, GD265/4/4 and GD265/7/3/14

NRS, Fishery Board for Scotland papers, AF38/117/1

NRS, Records of the British Fisheries Society, GD9/259

T M Devine, Clanship to Crofters' War: The Social Transformation of the Scottish Highlands, 1994

Iain Sutherland, Wick Harbour and the Herring Fishing, 1983

T M Devine, C H Lee and G C Peden (ed), The Transformation of Scotland. The economy since 1700. Journal of Scottish Historical Studies, May 2005

Kathryn L. Moore, The Northeast of Scotland’s Trading Links Towards the End of the Nineteenth Century. Evidence from the daybook of three ports: Aberdeen, Peterhead and Gardenstown. Journal of Social and Economic History, Vol. 21, Issue 2