Mills in Scotland

Mills in Scotland

In 2020, the Scottish Government is celebrating the Year of Coasts and Waters. In this article we delve into our archives to learn more about mills in Scotland.

Think of the word ‘windmill’ and it may conjure up images of the Netherlands and buildings with large sails turning in the wind near the water, or sitting by a field of grain. Since the mid-15th century, however, they have also been part of the Scottish landscape. Introduced from the Netherlands and England, the earliest reference to a windmill in Scotland was in Largo, Fife, in the mid-15th century.

The watermill had also become established in Scotland by this time, influenced by England where, by the 11th century, 6,000 had been built and by the 16th century were the largest source of motive power. Watermills were usually powered by water diverted from rivers and were used in a number of industrial activities from milling grain or producing cloth to grinding of ingredients for gunpowder and powering bellows for furnaces.

By the early 17th century, these structures were considered an important element in the community as both a source of livelihood and food production. In 1600, for example, King James VI by a Royal Charter conferred the rights of building within the burgh of Perth for wind ‘as well [as] water mills for the common and public utility and profit of the burgh.’ A windmill was an expensive, specialist construction, however, and by the late 1700s, cost up to three times the amount of a watermill to build.

Nevertheless, demand across the whole of Britain grew, and by the late 18th century there were as many as 50 windmills in operation across Scotland. Improvements in technology, met with an increase in cereal production, encouraged this growth which continued throughout the 19th century.

This was also the case with the watermill. Two types of corn mill (for making oat and barley meal) were built in Scotland. One was a simple design, made without gearing but which had a horizontal water wheel, and another, more complicated design, with a vertical wheel.Wealthier landowners were able to own and build the more complex mill and ensured that their tenants used it in the production of various commodities to generate income for the estate.

For both wind and water, more efficient mills were developed and built from around 1750. This was driven by changes in both farming and trade. New designs of water wheels were introduced alongside sturdier construction and more effective areas to dry grain in windmills. One modern watermill could do the work of six of the old styles.

As Ian L. Donnachie and Norma K. Stewart note, geography was an important factor when deciding where to construct these buildings.

Almost 75% of all recorded windmills, for example, were in areas with less than 30 inches of rain per year. This is evidenced in the drier east coast such as Moray, Buchan and East Lothian where high numbers were built. The west coast was also a popular location with exposed areas where high, lively winds powered the windmills in Ayrshire, Lanarkshire and the Machars. High, exposed sites, such as Eyemouth and Duncow were also taken advantage of for this purpose. Other mills were built for specific purposes such as grain milling and threshing which influenced their location and construction.

An example of a plan depicting a windmill. Shown here is a detail of the village and parish of Gorbals by Thomas Richardson, 1803.

National Records of Scotland, Crown copyright, RHP44858

Scotland was a prime location for watermills, being a country with steep rivers and, in many areas, high rainfall. This allowed water to be delivered to the top, or part of the way up the mill wheel and meant that Scotland’s mills required smaller mill dams, if they were needed at all, to ensure they had a constant supply of water. These mills were usually placed close enough to the river to minimise the length of the channel to bring water to the mill-dam, but far enough from the river to avoid being flooded in times of heavy rain. Conversely, as may be expected, flat, low-laying land with slow moving burns or rivers were home to far fewer watermills as these required the assistance of dams, ponds or wells to help with waterflow.

Detail from plan of Millhill, Aberdeenshire, depicting a ‘miln’ (watermill)

National Records of Scotland, Crown copyright, RHP2249

The oldest remaining watermill in Scotland, Preston Mill, is found in East Lothian. A mill has sat on the site since the 16th century, although the present mill dates from the 18th century. It was used for a commercial purpose until 1959, and today is now managed by the National Trust for Scotland who welcome visitors on tours.

Windmills and watermills began to wane in popularity towards the end of the 19th century as steam power replaced their work, pushing ahead to meet the ever increasing demands of the industrial revolution. Other factors, such as the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846, led to a new demand on imported wheat, and milling became more reliant on steam mills. Wheels from watermills were also often removed to install more efficient turbines. Many fell into a state of disrepair and machinery and sails were stripped from the buildings and sold. For some opportunists, the valuable parts were a temptation waiting to be stolen and sold on the black market.

The windmill in Inverness-shire, shown in the plan below, was targeted by Alexander Fraser in the Police Court at Inverness in July 1861. The Inverness Courier reported that he had ‘stolen a quantity of lead, weight 61 ½lbs from the roof of the granary, Windmill of Kessock… he was sentenced to be imprisoned for 60 days.’

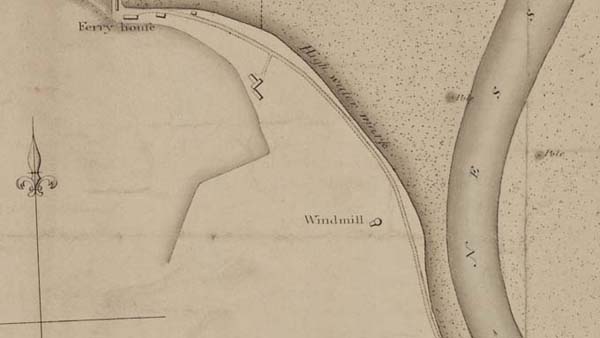

Plan of the Kessock Ferry showing the confluence of the Rivers Ness and Beauly, Inverness-shire March 1832.

National Records of Scotland, Crown copyright, RHP117/2

By the late 19th and early 20th century, the surviving windmills were mainly based in smaller, rural communities. There was an interest, however, in trying to utilise the power of these structures for uses other than pumping water on farms, for irrigation or grinding corn. The Montrose Standard, in September 1892, for example, told the story of Professor Blyth of Glasgow University who had been successful in lighting his house by the power of electricity by using a windmill. This was done by attaching 13 accumulators to an old English type windmill with four arms, 14 feet in length, and canvas sails. He noted that windmills had the potential of powering lighthouses, stating that they ‘are always in exposed situations where wind is plentiful’, and that lighting private country mansions and for factories ‘so situated that a suitable mill could be placed on the roof.’ Despite wind being free and accessible, he added that ‘it is of very intermittent nature…[and] storage cells or accumulators…are now highly efficient, though a little too expensive.’

Nearly 30 years later, The Sunday Post, in November 1919, also questioned why more use was not being made of windmills and stated that ‘it is surely possible to find some new and practical uses for the old windmill…in the face of the present shortage of coal, we cannot afford to ignore any potential source of power.’ The article continued by quoting a builder of windmills who said ‘I have seen a steel windmill which is reckoned the strongest, safest, and most reliable on the market…A mill of this type could be utilised economically as a means of propulsion in small electric power stations in country districts. If a series of windwills were erected they would eliminate the cost of fuel, and should be very valuable for generating power for light in village and small towns.”

Despite these ideas, the enthusiasm and commitment to re-developing windmills was only felt in small groups and wasn’t enough to compete with large scale factories and production lines.

Rural watermills became less economical to run as the demand for stoneground flour fell and modern technology competed with quicker and cheaper methods. Today, Blair Atholl watermill is one of the last three operational watermills in Scotland. A mill has existed on the site since the 1590s and has stoneground wheat, oats, rye and spelt in the traditional manner apart from a period between 1929 when it was forced to cease production due to modern competition until 1977 when it was restored. It can be visited today.

Resources in the National Records of Scotland (NRS) relating to water and wind mills

Maps and Plans

NRS holds a series of records known as the Register House Plans (RHP). It is an artificial collection of around 170,000 topographical plans, marine charts, architectural and engineering drawings.

A selection of these can be found and viewed for free on the ScotlandsPeople website under the maps and plans search. Otherwise, please visit our online catalogue. Digitised maps and plans can be viewed on the Virtual Volumes system in the Historical Search Room, General Register House, Edinburgh.

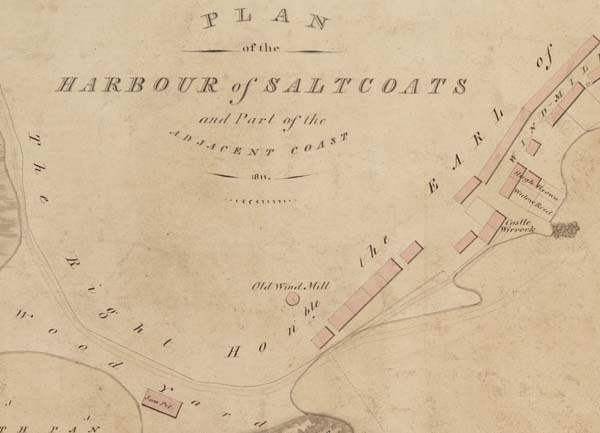

An example of the types of plans you can discover through the cataglogue. This image shows a detail from a plan of the harbour of Saltcoats and part of the adjacent coast, Ayrshire, 1811. It is available to view on https://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk/maps-and-plans. National Records of Scotland, Crown copyright, RHP55

Wills and Testaments

If someone lived at, worked in, or owned a windmill upon their death, their will may record this information. Wills can also be helpful in tracing ownership of a windmill. For example, when John Clark of ‘windmill of Annan’ died in 1830 he recorded ‘in favour of Robert Clark in Burnfoot of Springdike my second son and his heirs… all and whole that part of the lands of Anan Acre and Addisons Close or Johnstone Field, with the Windmill Kiln and whole stances built thereon…’ (ref. SC15/41/5 page 54). This windmill sat 1/4 mile east of the River Annan and was a freestanding round tower with added wings to the east, west and south. It was eventually demolished and replaced by Provost Mill.

Valuation Rolls

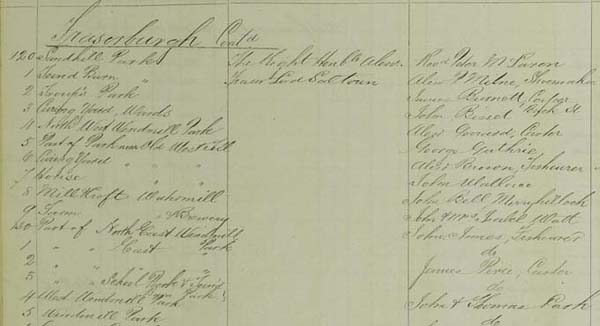

Valuation rolls, records of property ownership compiled for collecting local taxation, can be helpful in discovering where a windmill or watermill was based, the owner, tenant and occupant of the property. The 1875 valuation roll for Fraserburgh, for example, records Lord Saltoun as the owner of a mill and croft, watermill, and other lands known as ‘Windmill Park’ ‘West Windmill Park’ and ‘Part of East Windmill Park.’

National Records of Scotland, Crown copyright, Valuation Roll, 1875, Fraserburgh, VR87/62 page 6

The valuation rolls also show the influence of windmills in town planning. A search of the 1855 valuation rolls for the word ‘windmill’ return locations and street names such as: Windmill Hill, Windmill Lane, Windmill Street, Windmill Farm, Windmill Brae, Windmill Street.

For further information about the records we hold, please visit our research guides page.

Resources Used

- National Records of Scotland (NRS), Inventory; disposition and settlement, Dumfries Sheriff Court, SC15/41/5 (John Clark, 16 March 1830)

- Bishop, Paul, and Munoz-Salinas, Esperanza (2013), Tectonics, geomorphology and water mill location in Scotland, and the potential impacts of mill dam failure (accessed 18/08/2020)

- Ian L. Donnachie and Norma K. Stewart, Scottish Windmills – An outline and inventory

- Jesmond Dene Old Mill, History and Technology of Watermills, The History of Watermills (accessed 21/08/20)

- Thomas McLaren, 'Charter of Confirmation of the whole Rights and Privileges of the Burgh of Perth, granted by King James VI, 15th Nov. 1600 found in Old Windmills in Scotland, with Special Reference to the Windmill Tower at Dunbarney, Perthshire'. Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scot. Vol. LXXIX. 1945. P.10

- Canmore, Annan (accessed 13/07/2020)

- Canmore, Monkton Windmill, Whiteside, South Ayrshire (accessed 01/07/2020)

- www.scran.ac.uk, Manufacture Water-Powered Grain Mills

- www.geograph.org.uk, Watermills