Treatment or Punishment? The Introduction of Force-Feeding in Scotland

Treatment or Punishment? The Introduction of Force-Feeding in Scotland

Force-feeding, or ‘artificial-feeding’ of suffragettes, as the Government authorities euphemistically called it at the time, is a widely recognised part of the fight for women’s suffrage in the early 1900s. However, many may not be aware that the start of this practice was not a unified process across Great Britain. In this article we will look at why suffragettes went on hunger strike, and the introduction of force-feeding into Scottish and English prisons.

Firstly, why did suffragettes hunger-strike? The strike was not against their imprisonment or as a form of protest against the lack of female enfranchisement; it was a protest against the degradation of being treated as ordinary criminals of the second and third division. Different rules applied to prisoners depending on what division they were placed in. The first suffragette to hunger-strike was Marion Dunlop in 1909 who was arrested and imprisoned in Holloway Prison on 5 July 1909. Upon entering the prison, Dunlop used her own initiative to demand the right to be recognised as a political prisoner, and as such to have first-division status and treatment (see 'Treatment of Prisoners' for a comparison of the different divisions).

“I claim the right recognized by all civilized nations that a person imprisoned for a political offence should have first-division treatment; and as a matter of principle, not only for my own sake but for the sake of others who may come after me, I am now refusing all food until this matter is settled to my satisfaction” (Hunger Strikes, Spartacus Educational).

Afraid that Dunlop might die and become a martyr for the cause, she was released from prison after refusing food for three and a half days. Subsequently, imprisoned suffragettes frequently went immediately on hunger-strike with the aim of being recognised as political prisoners, and, as their actions gained considerable press attention, this was arguably also used to increase publicity and sympathy for their cause.

The death of any of these women in prison would have been of grave concern to the Government as, if it were to happen, it would likely add more strength to the suffragette cause. So why did the Government refuse to recognise them as political prisoners? Simply, because to do so would have added legitimacy to their claim. Indeed, in order to try and appease the suffragettes, the then acting Home Secretary Winston Churchill introduced rule 243a in 1910, which allowed suffragettes comforts equivalent to those under first division, but denied them the status of political prisoners (‘English Society and the Prison: Time, Culture and Politics in the Development of the Modern Prison’). However, hunger-strikes continued and the Government responded by introducing ‘forcible-feeding’.

Force-Feeding

See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Force-feeding is a painful and often dangerous process of forcing a person to take in a nutritional substance against their will, most commonly via a plastic feeding tube. In the National Records of Scotland (NRS) there is correspondence, news cuttings and written documentation within the Scottish Home and Health Department records which detail the painful and frightening experience of force-feeding, and the disastrous effect it had on an individual’s health.

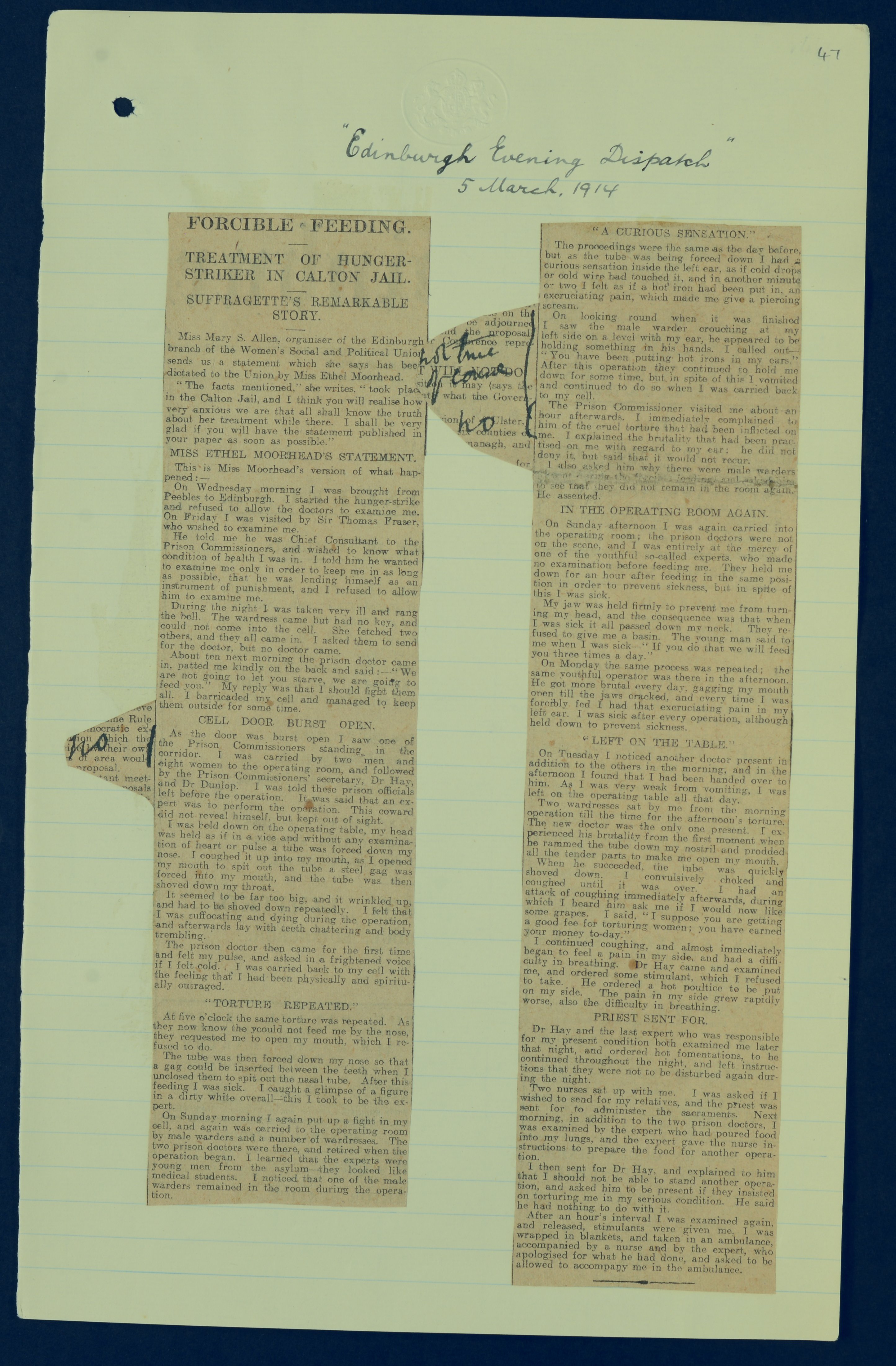

Criminal Case File for Ethel Moorhead. News cutting, ‘Edinburgh Evening Dispatch 5 March 1914’ (National Records of Scotland, HH16/40)

At the time, force-feeding was advocated by the Government as a way of preserving life while ensuring the prisoners served their full sentence. The records suggest, however, that it was also employed as a warning to those participating in militant suffrage. As the practice continued, many doctors spoke out against medical professionals who participated, pointing out that force-feeding a healthy and struggling patient was tantamount to a form of torture. The practice also consistently failed to achieve the Government’s claimed purposes, frequently damaging the health of the prisoners and failing to keep them in prison for the duration of their sentence.

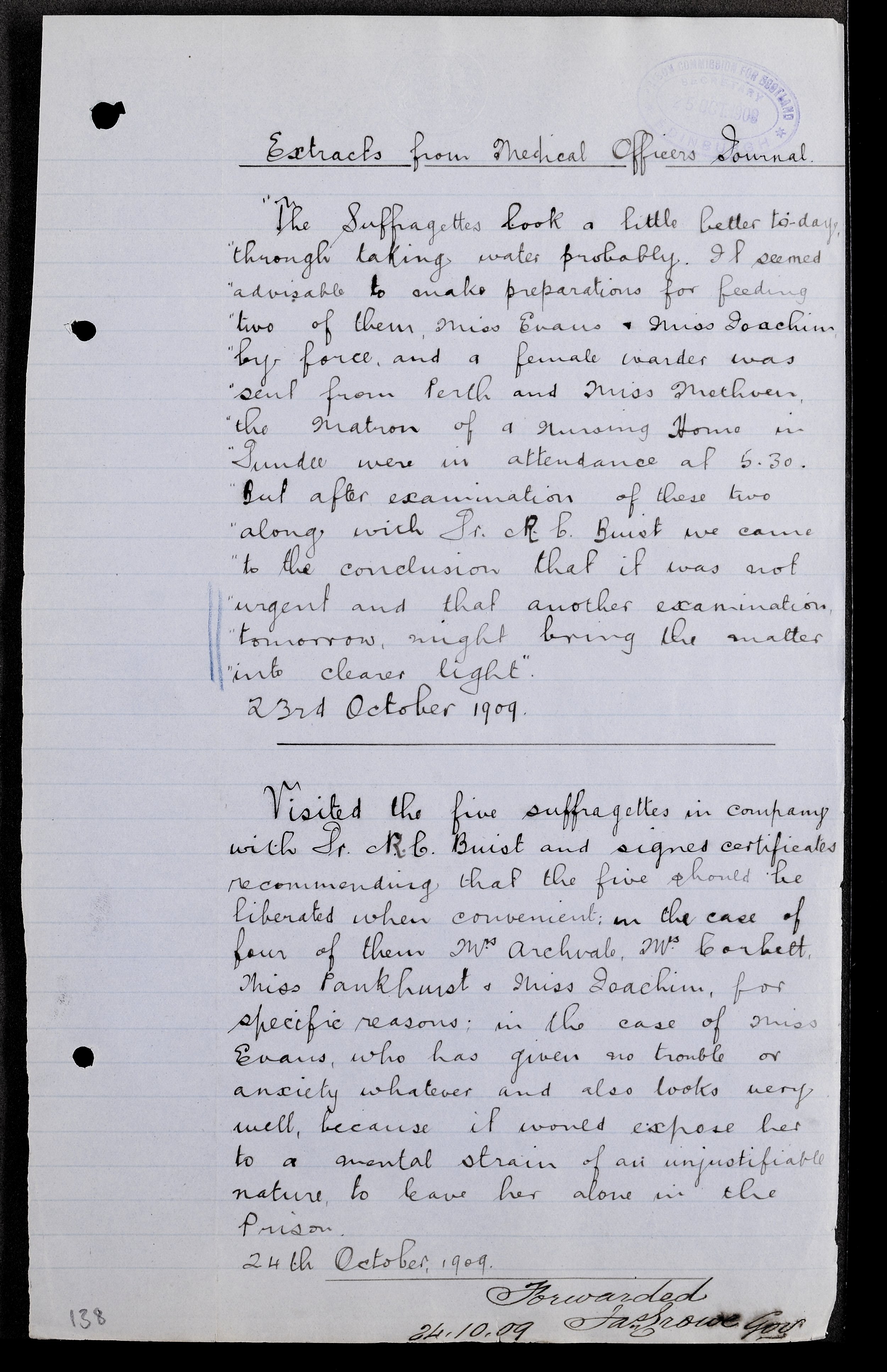

In the NRS Home and Health records we hold the prisoner case files for many of the suffragettes who were imprisoned in Scotland, including Fanny Parker, Frances Gordon, Ethel Moorhead and more (to see the full files online, visit ‘Malicious Mischief? Women’s Suffrage in Scotland’). These records show that Scotland took considerably longer to resort to force-feeding than her English counterparts, despite the fact that there was discussion of how it could be administered as early as 1909. Records relating to suffragette activities in Abernethy and Dundee reveal that on the 23 October 1909, preparations were made in Dundee prison to force-feed two suffragette prisoners, Miss Joachim and Miss Evans. However, upon further examination it was decided that the women should be liberated instead.

Police service files detailing the suffragette’s activities in Abernethy and Dundee (Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland HH55/323)

“It seemed advisable to make preparations for feeding two of them, Miss Evans & Miss Joachim by force, and a female warder was sent from Perth and Miss Methoen the matron of a nursing home in Dundee were in attendance at 5.30…. Dr R. C. Buist… signed certificates recommending that the five should be liberated when convenient…”

It was not until 21 February 1914, that the first incident of force-feeding in Scotland took place. Ethel Moorhead – alias Edith Johnston, Mary Humphreys or Margaret Morrison – was repeatedly arrested for outrageous militant acts. On 15 October 1913, both Moorhead and Dorothea Chalmers Smith or Lynas were convicted of house-breaking and attempted fire-raising and were released under the controversial Prisoners (Temporary Discharge for Ill Health) Act - commonly called the ‘Cat and Mouse’ - Act after five days of fasting. Once recovered, Moorhead disappeared but was re-arrested and imprisoned in Calton Gaol, Edinburgh, with force-feeding commencing shortly afterwards. Moorhead became the first suffragette force-fed in Scotland.

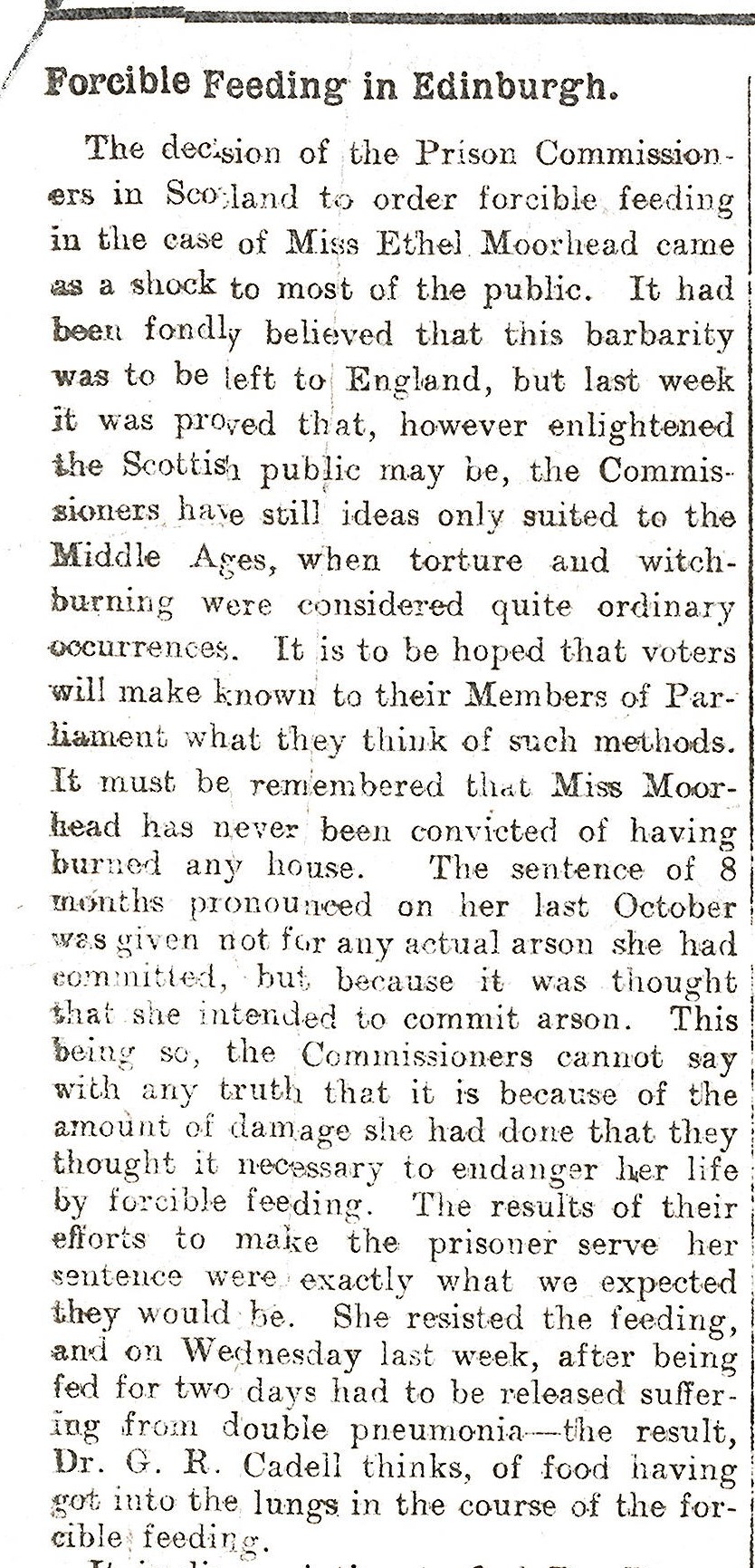

NRS records suggest that the actions of the Scottish authorities deeply shocked the public, as many had believed that Scotland would not lower itself to such barbarous acts.

Criminal Case File for Ethel Moorhead, news cutting from issue of ‘Forward’ 7 March 1914 (Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland, HH16/40/7)

In comparison, the first instance of force feeding in England occurred in Winson Green Prison, Birmingham, in 1909, two weeks after the first hunger-strike by Marion Dunlop. So why the disparity between Scotland and England? This could be for a number of reasons. Unlike their English sisters, Scottish suffragettes took considerably longer to adopt aggressive militant methods of protest at home, although it should be noted that Scotswomen did frequently travel south of the border to take part in militant campaigns. It is possible that the thought of participating in window smashing and arson in their hometown where they would be recognised was too distressing, thus they travelled to where they could conduct themselves in relative anonymity. At the beginning of 1913, the favoured militant acts in Scotland were attacks on post boxes; corrosive acid was poured inside, destroying the contents. However, as the fight for suffrage continued, the scale of the attacks on property escalated, with pavilions, halls, mansions and public buildings becoming targets. It is possible that the more peaceful tactics employed, at least for a time in Scotland, meant that the Government was even more cautious in attempting forcible-feedings for fear of a more outspoken public backlash.

It may also be that the doctors were more concerned about risking the health of their patients. Although it is clear from our records that forcible-feeding was discussed, the extracts from the medical officer’s journal reveal a reluctance to rush to force-feeding if it was deemed unnecessary. While it would be pleasant to assume that the doctors in charge were looking to maintain their professional mission of treating sick patients, and resisting an attempt to employ their services as a form of penal punishment, it is really not possible to say.

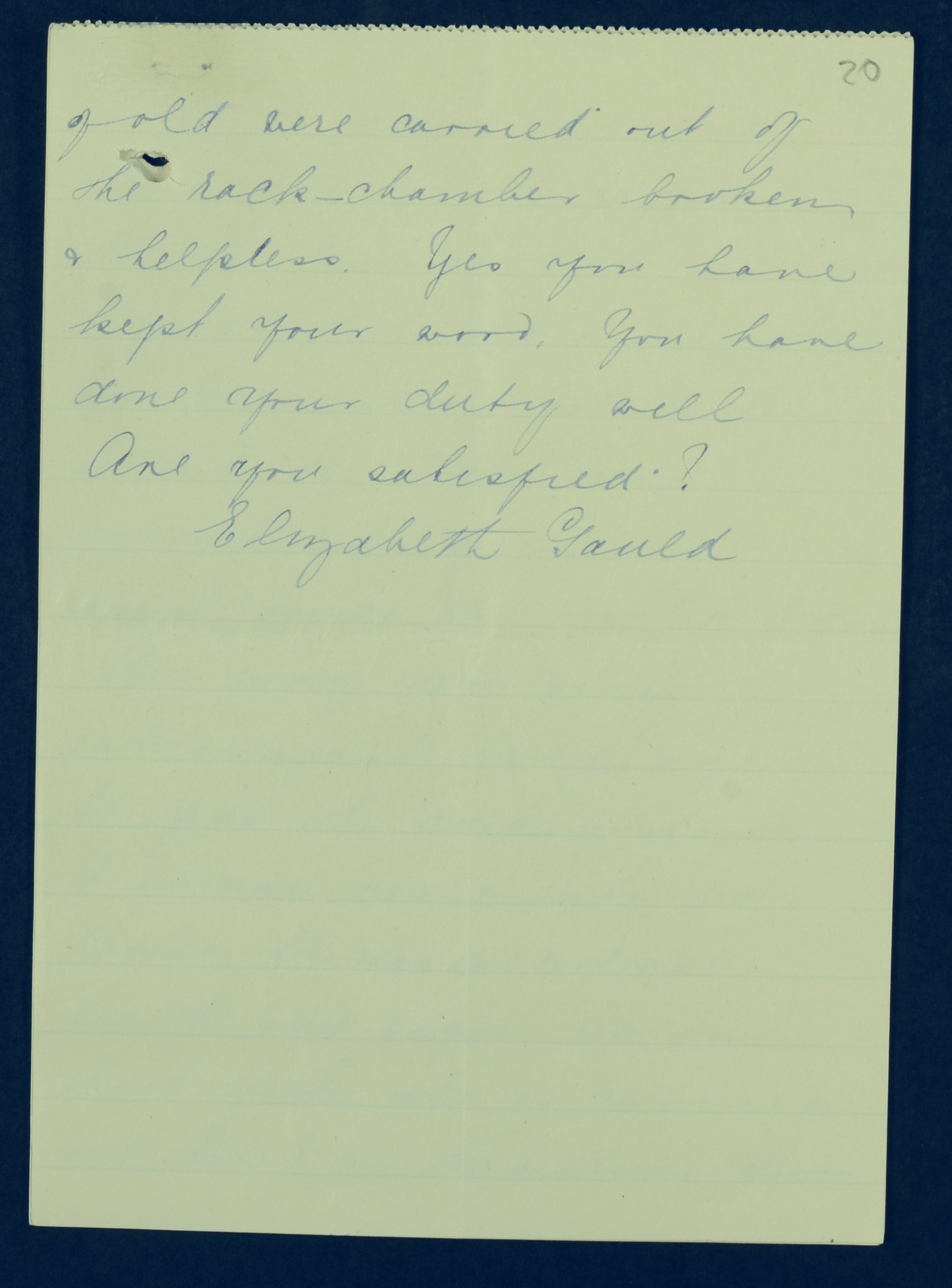

Public Response

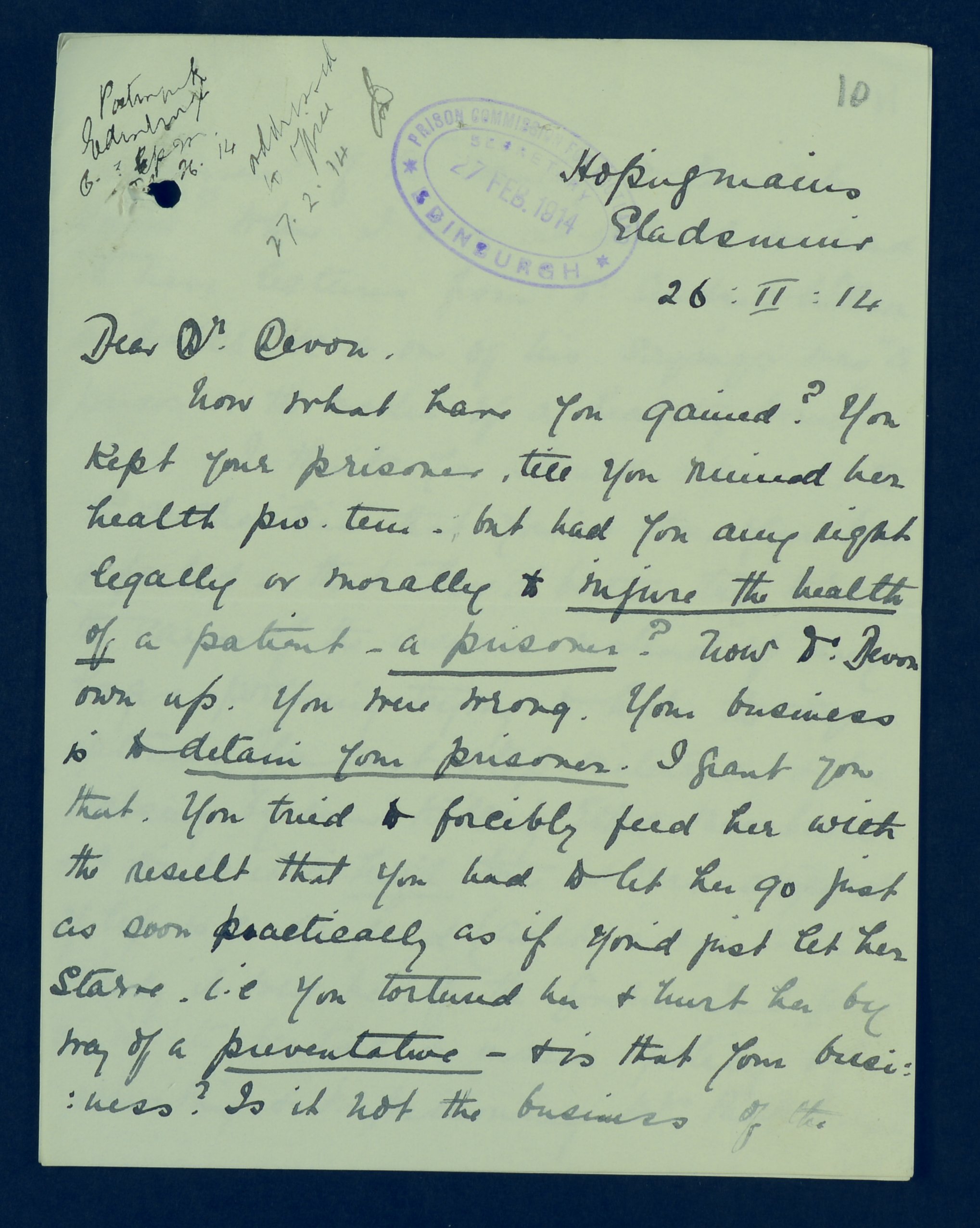

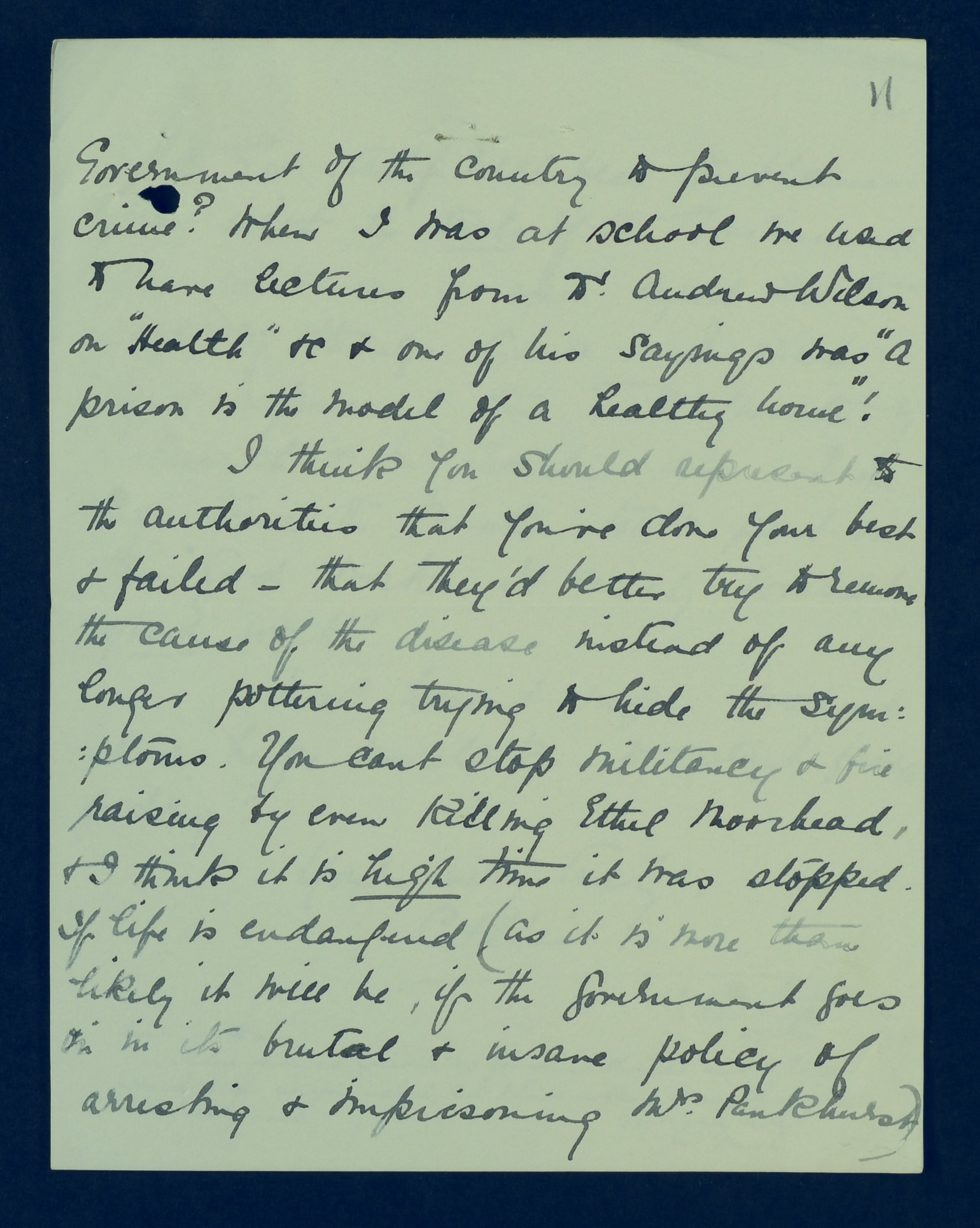

Force-feeding as a form of ‘treatment’ was unpopular with the public, with even the first incident in Birmingham, repeatedly raised in Parliament (MP Keir Hardie questioned the Government on this matter for the first time in 1909). NRS records show the shock and anger at force-feeding in Scotland from the moment it began, with the blame for its introduction laid at the feet of Dr James Devon. As the letters below demonstrate, there were strong reactions to this course of action.

Criminal Case File for Ethel Moorhead, letter from C. Blair to James Devon, 26 February 1914 (National Records of Scotland, HH16/40). Transcription of the letter.

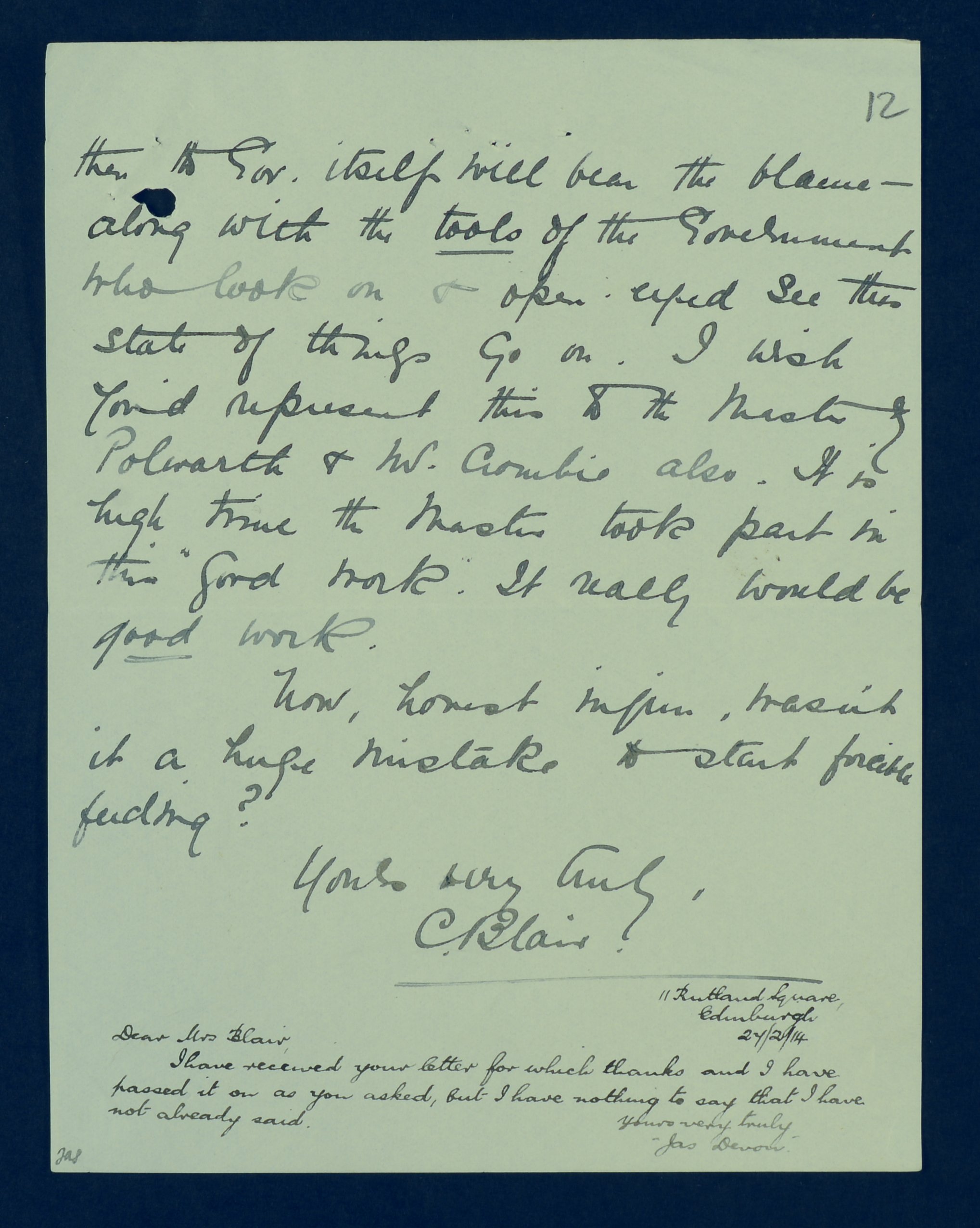

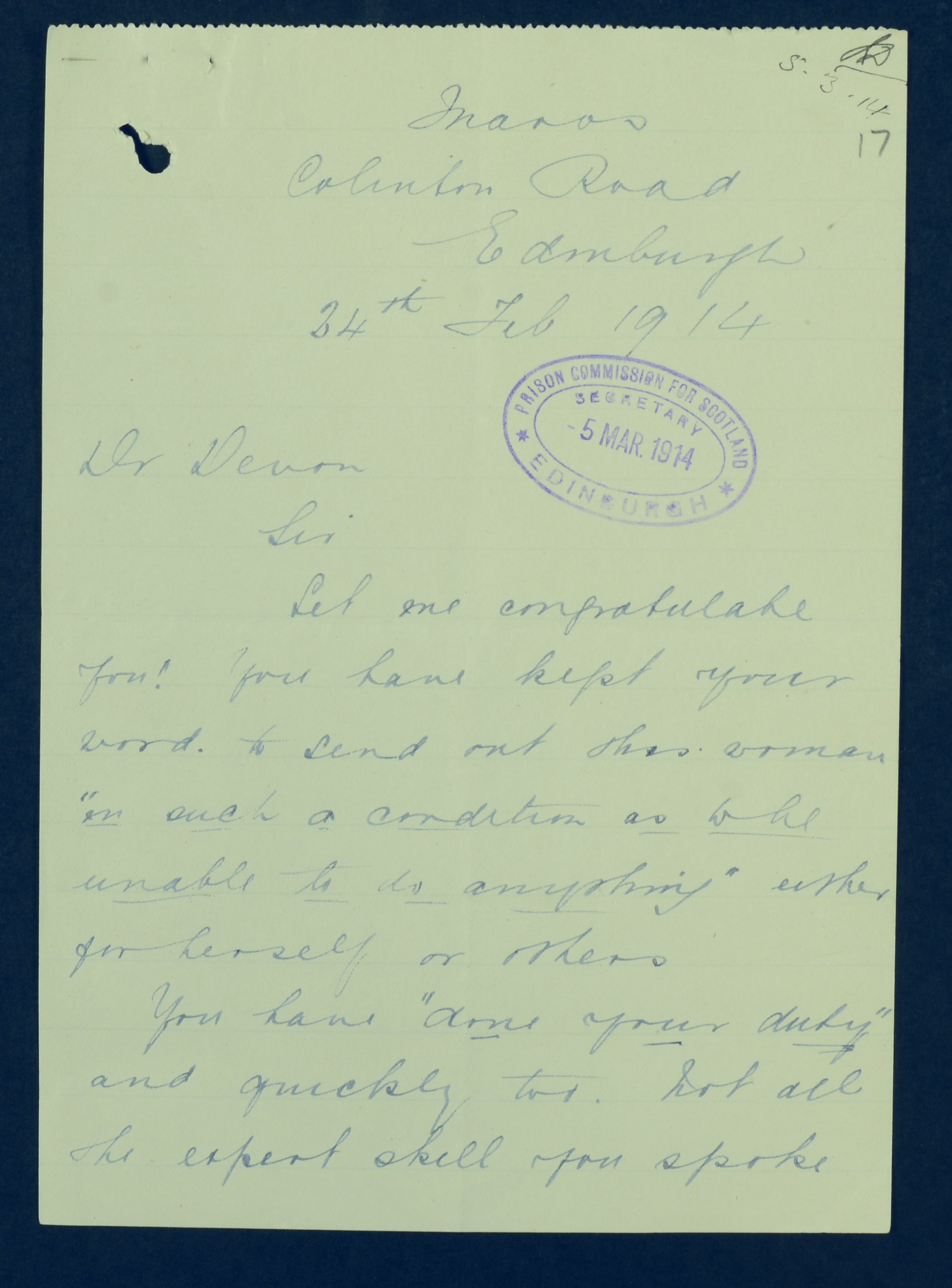

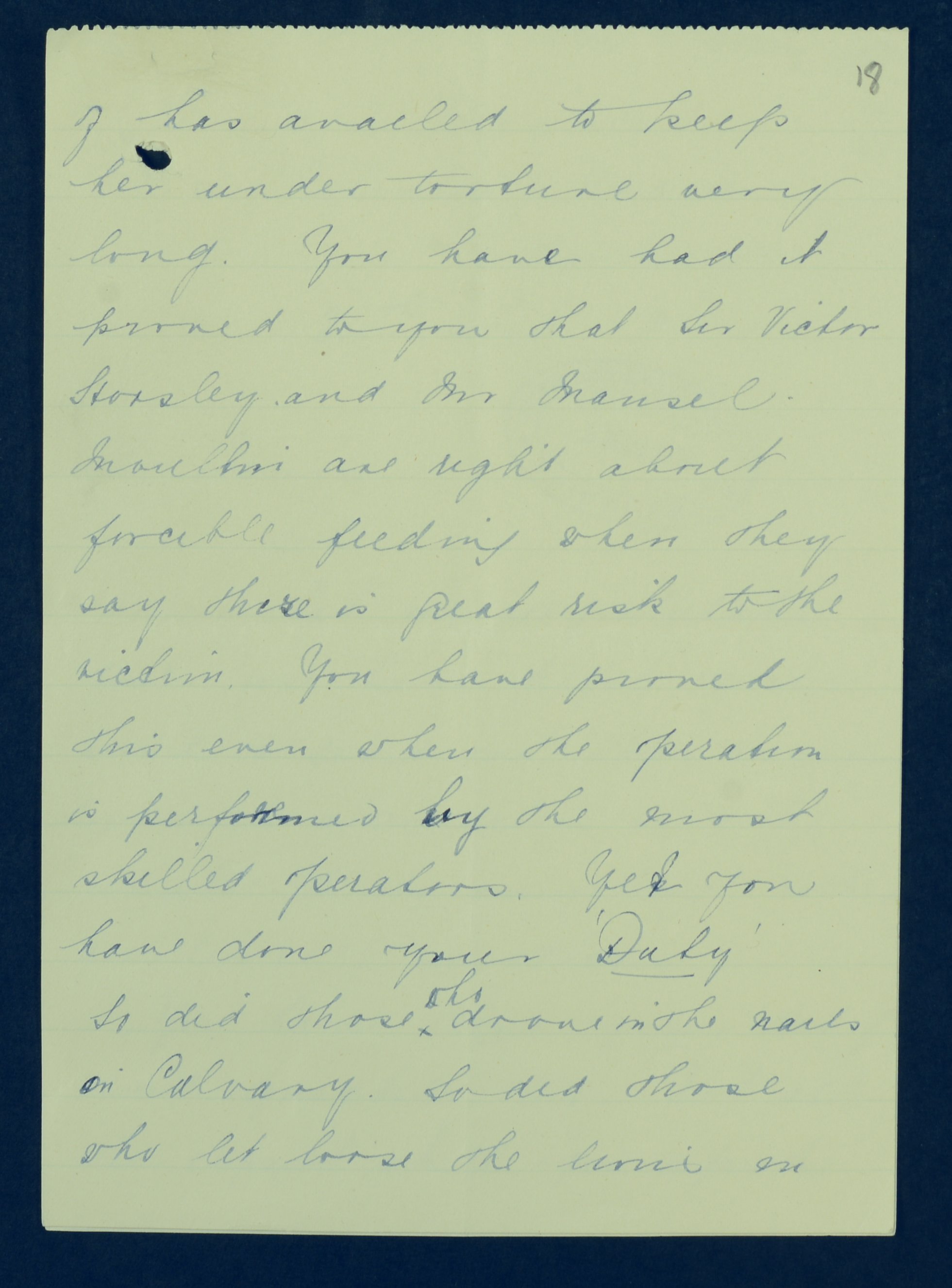

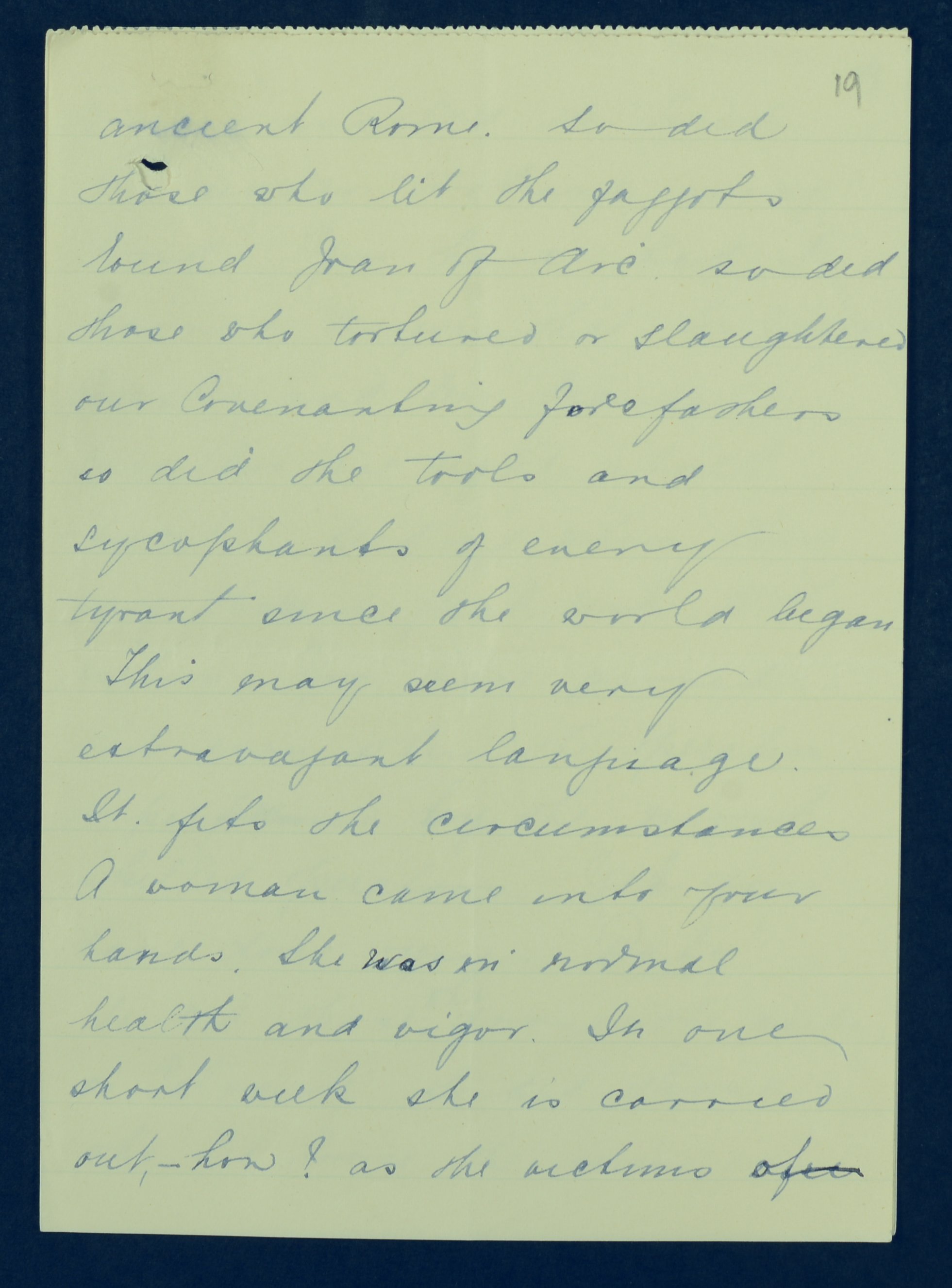

Criminal Case File for Ethel Moorhead, letter from Elizabeth Gauld to James Devon, 24 February 1914 (National Records of Scotland, HH16/40). Transcription of the letter.

Of course, it was not only women outraged by this behaviour, but also men who – regardless of their views on suffrage – felt it was a crime to inflict bodily harm on a women for their involvement in militant suffrage. As the published excerpt from the article ‘Militant Suffragists in Newcastle’ by H. N. Brailsford below demonstrates:

Cropped excerpt from the article 'Militant Suffragists in Newcastle', 11 October 1909 by H. N. Brailsford (National Records of Scotland, HH16/37)

James Devon’s response to these accusations and his view on force-feedings are recorded in an interview with the WSPU in newspapers of the time:

Cropped excerpt from an Edinburgh Evening News news cutting, 'The Militants and the Prison Commission. Forcing Feeding in Calton', 25 February 1914 (National Records of Scotland, HH16/40/5/15)

It is surprising that Dr James Devon appears to openly admit that force-feeding was not being conducted to ensure the health of the prisoners, as had previously been claimed, but rather as a way to disable them from taking further militant action on release. This admission, along with the prioritisation of property over human life from a doctor, was rightly recognised as a blight against the medical profession and the authorities.

Force-feeding per rectum

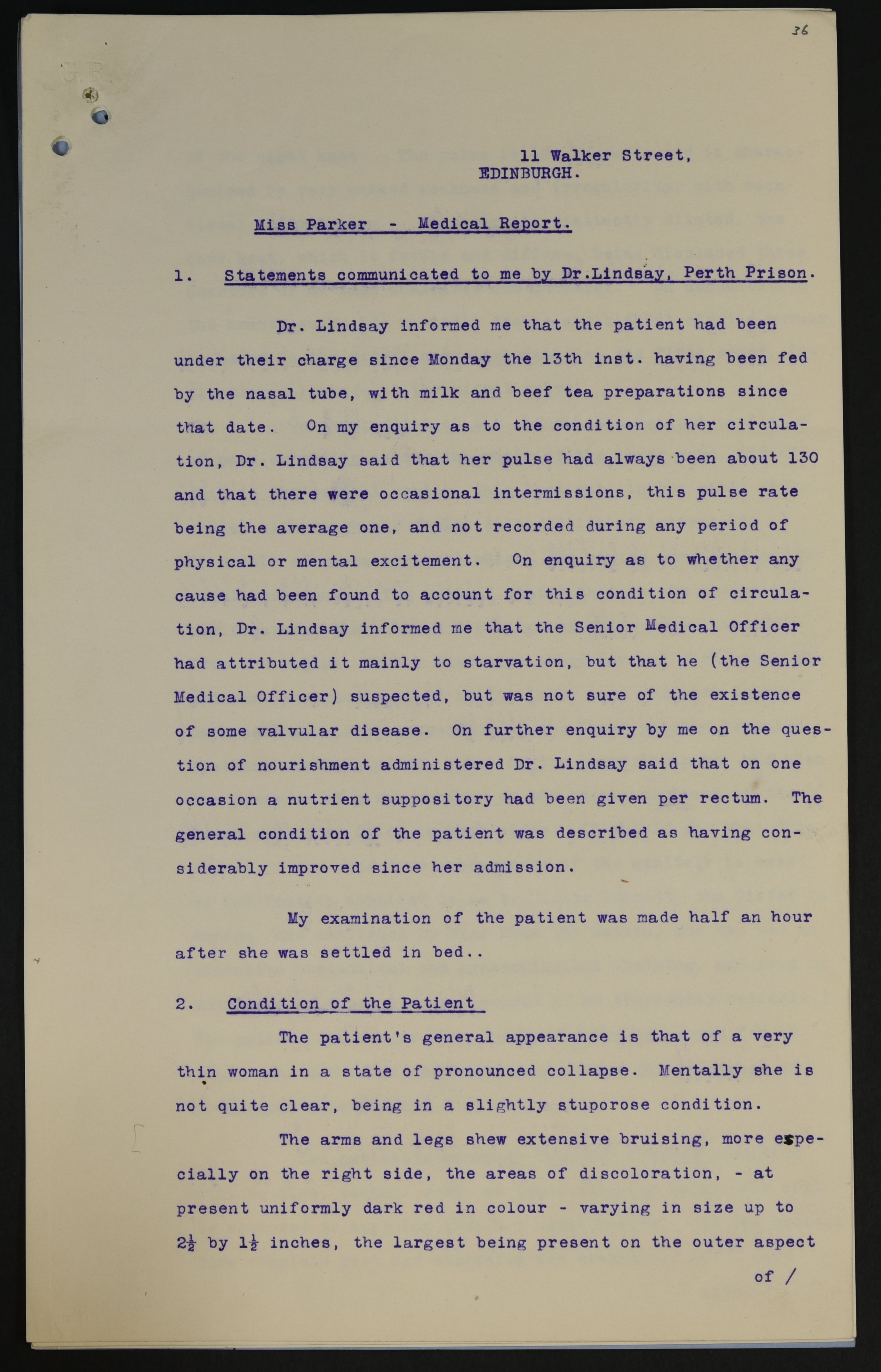

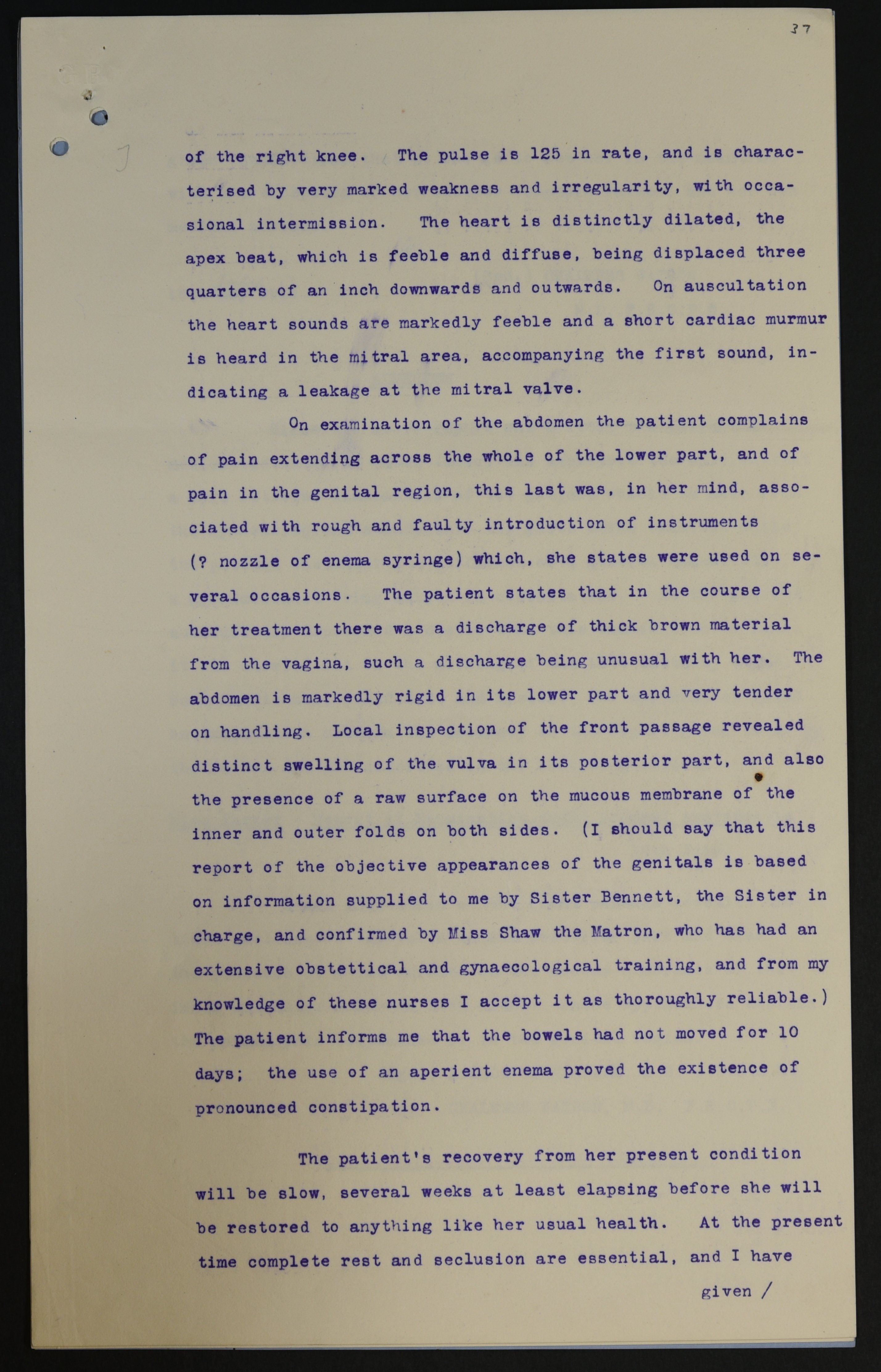

Perhaps one of the more surprising aspects noted in these records is the reference to force-feeding by the rectum. At least three suffragettes are recorded as being subjected to this treatment; Maude Edwards, Fanny Parker and Frances Gordon. The most detailed account relates to the feeding of Janet Arthur, a.k.a Fanny Parker, with records preserved on her feeding, physical condition and the refusal of the authorities to directly answer questions regarding her health to her relatives.

News clipping from an unidentified newspaper reporting on the force-feeding of Janet Arthur, alias Fanny Parker, undated (National Records of Scotland, HH16/43/9)

Fanny Parker’s account of feeding by the rectum undoubtedly caused shock, particularly as this was once again conducted by force and appeared to cause injury to the front of Parker’s genitals, causing pain and soreness that lasted for several days.

The large volume of records relating to Janet Arthur/Fanny Parker were likely created because news of her condition reached her influential family, who made enquiries as to the standard of her health.

Army recruitment poster featuring Lord Kitchener (Eybl, Plakatmuseum Wien/Wikimedia Commons)

Fanny Parker was the niece of Lord Kitchener - of ‘Your Country Needs You’ fame - and there are many notes in the criminal case file (NRS, HH16/43) documenting her brother, Captain Parker’s enquiries about her condition. These documents paint a revealing picture, with Government authorities reluctant to allow an independent doctor in to examine Fanny Parker, but also reluctant to out-right lie about the state of her health. For example, the telegram below between the Prison Commissioners and the Governor of Perth Prison reveals that at no point is the medical officer willing to confirm that Fanny Parker is in good health, despite the fact that this is the advertised purpose of force-feeding suffragettes:

Criminal Case file for Janet Arthur, alias Fanny Parker (Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland, HH16/43)

The final reply that the authorities supply reads: “Prison Janet Arthur’s condition is as good as can be expected in view of her conduct”. Other than having the worrying impression of a group of people attempting to get their story straight, there are also uncomfortable tones of victim blaming rather than any acknowledgment of the commandeering of the medical profession to deliberately damage a patient’s health. These records document Parker’s ’treatment’ including notes on attempted feedings and the number of ‘enules’ (suppositories) administered. They also report that throughout this process, Fanny Parker had not yet been convicted.

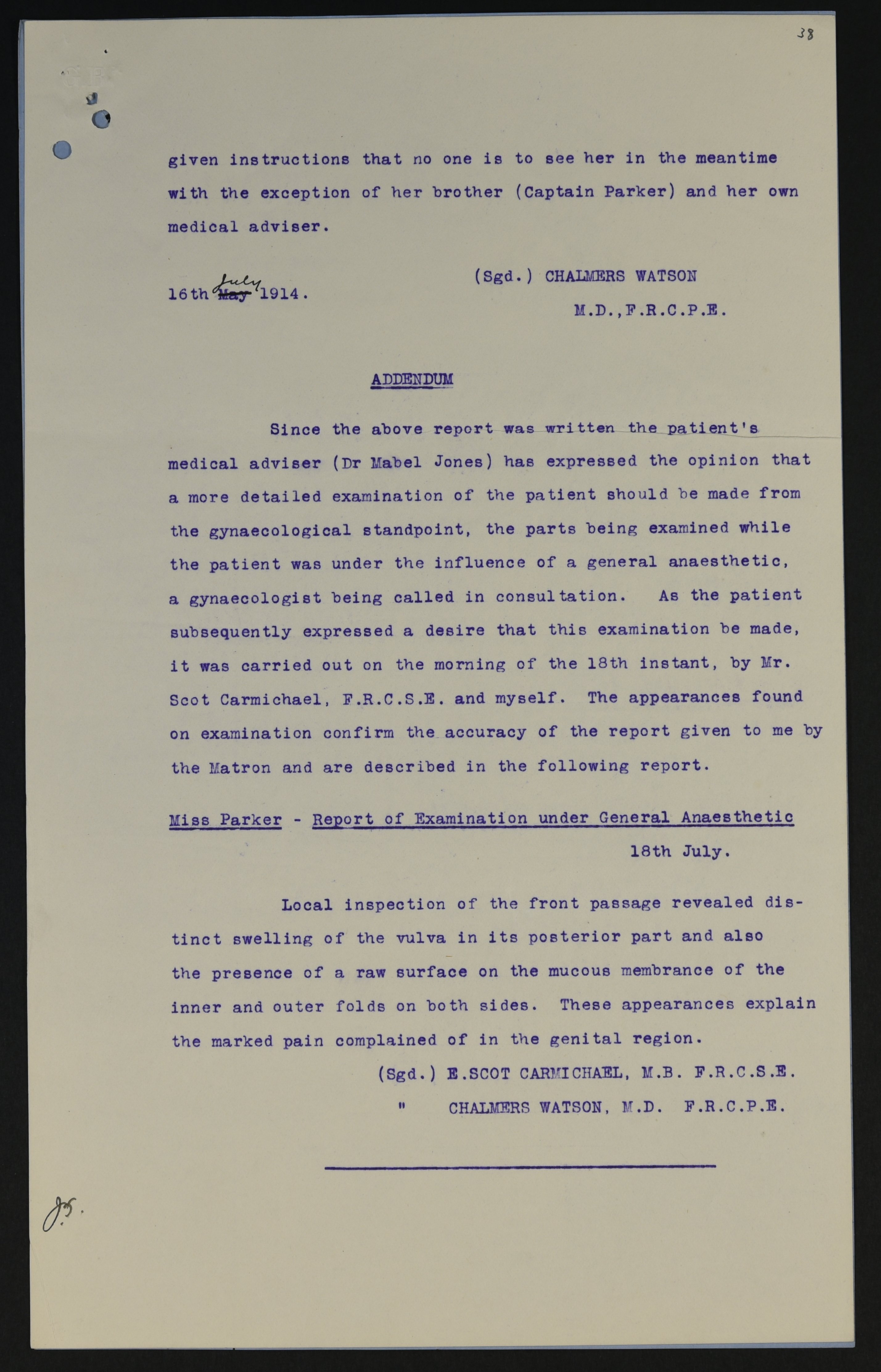

Eventually, Fanny Parker is examined by an external doctor with the full report appearing to confirm her version of events. This examination was conducted by Dr Chalmers Watson who supplied a copy of the report both to Captain Parker, and to Senior Medical Officer Dr Lindsay at the prison, prefaced with the comment:

“I sincerely hope that I will have no more medical experience of forcibly fed women”.

Criminal case file for Janet Arthur, alias Fanny Parker (Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland, HH16/43)

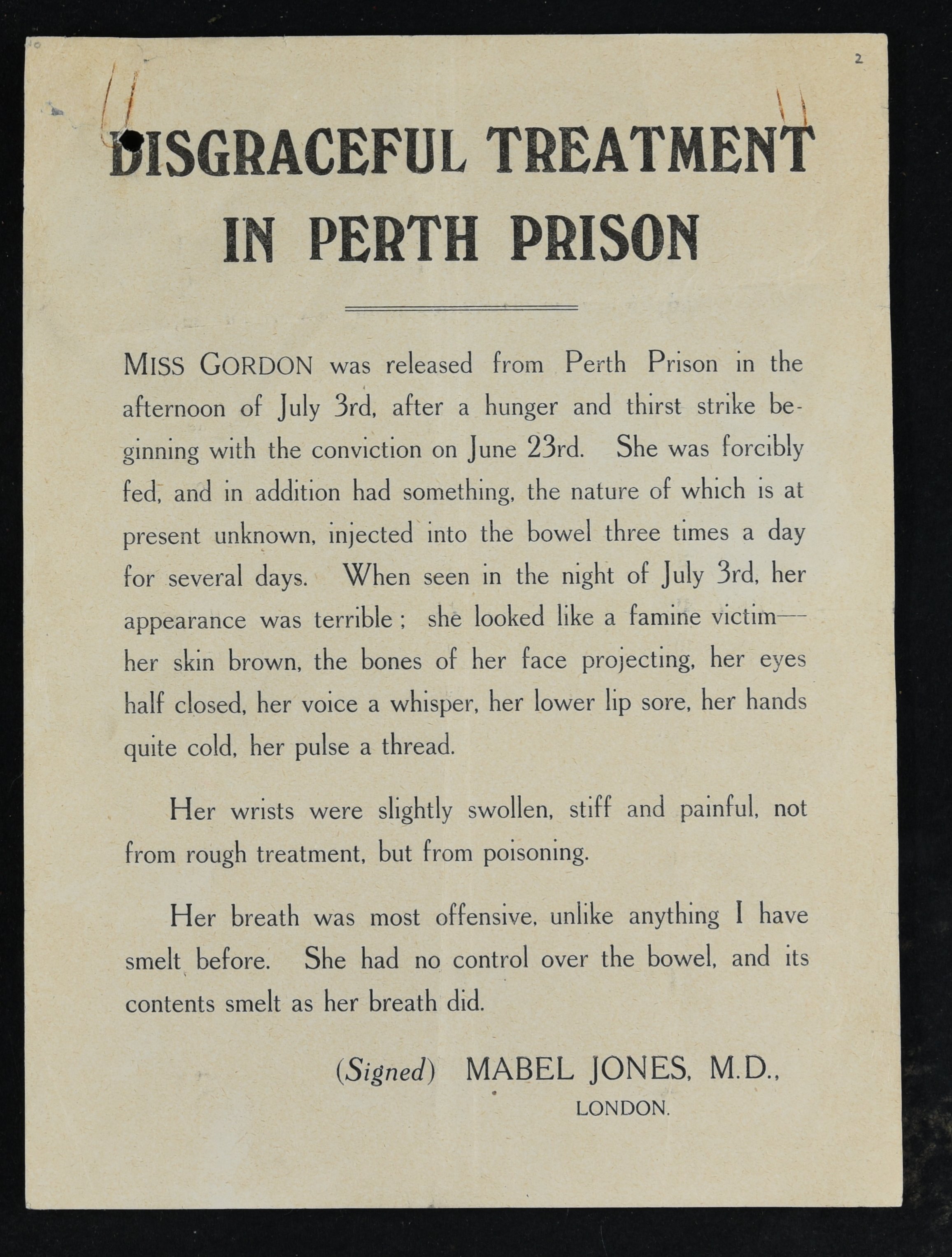

Frances Gordon (HH16/46)

In the criminal case file about Frances Gordon, there are not only details of the administration of ‘nutrient enemata’ but also speculation of self-drugging. A report on Frances Gordon’s release by Dr Mabel Jones details the sickness caused by force feeding:

Leaflet from the criminal case file for Frances Gordon (National Records of Scotland, HH16/46)

However, the prison medical officer’s notes suggest that Frances Gordon was very unwell before she entered the prison, and as such there is speculation that this was a plot by the suffragettes to gain early release, as well as fuel for their propaganda against the authorities. These speculations extend to a theory from Scotland Yard that the suffragettes had secured access to a supply of emetine which they intended to smuggle into the prison in the form of buttons! These could then be taken at will to induce sickness. There may be some merit to this suspicion as suffragette Mary Richardson, upon admission to Holloway prison, was searched and found to be carrying emetine tablets. However, there is no evidence as yet to suggest that they succeeded in fashioning these tablets into buttons.

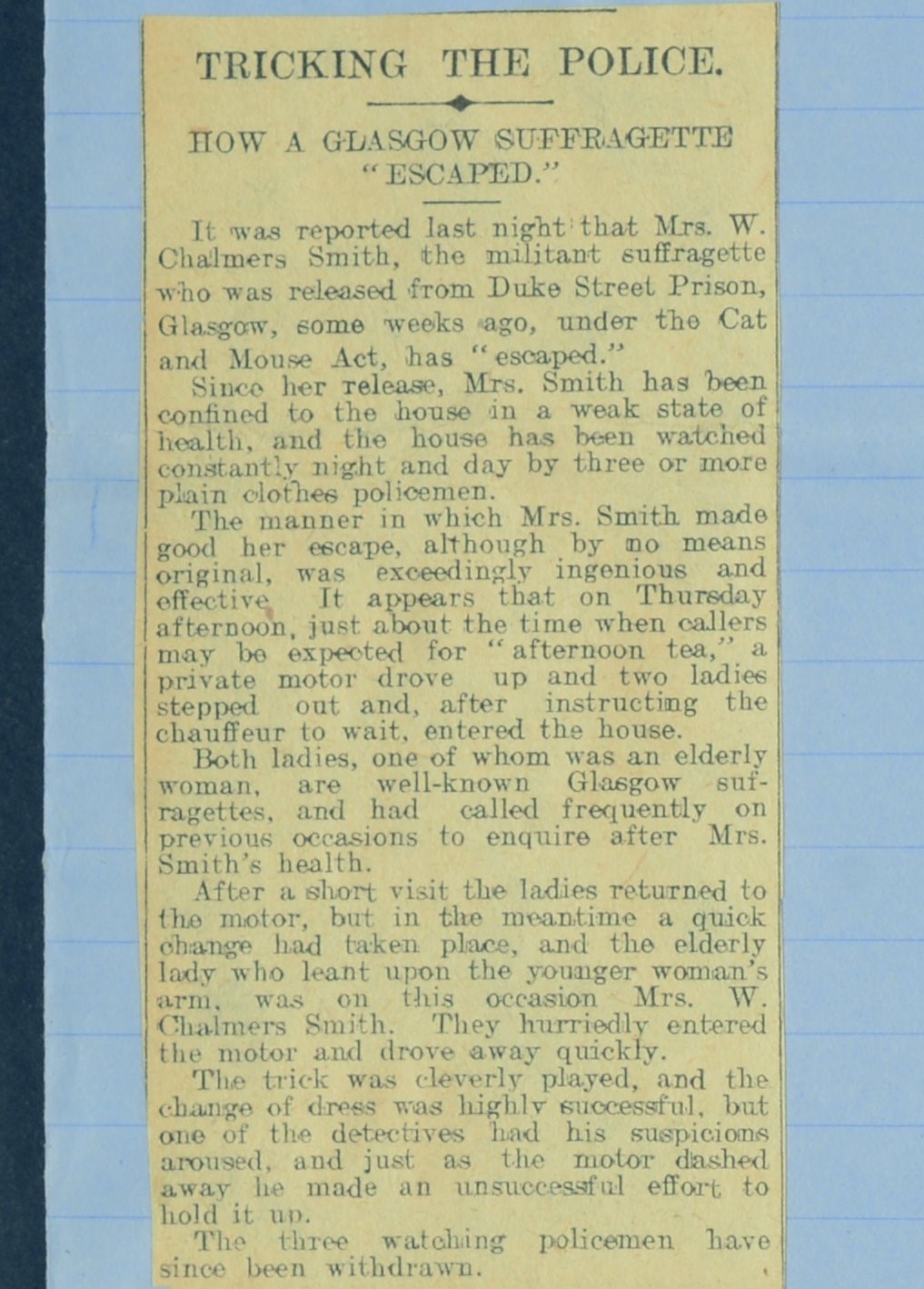

As the unpleasant and painful process of force-feeding was widely publicised by the WSPU publicity machine and by concerned medical professionals, the Government eventually introduced the Temporary Discharge for Ill-Health Bill in April 1913, which became commonly known as the ‘Cat and Mouse Act’. This gave the authorities the power to set hunger-strikers free for a short period of time under license, that they might recover from their fast and be rearrested to serve the remainder of their sentences. While a clear attempt to save face, Government authorities were equally thwarted in their attempts to re-arrest ‘mice’ suffragettes who often escaped in disguise!

Daily Record and Mail news clipping, 2 November 1913 (National Records of Scotland, HH16/40)

Despite these futile efforts, neither side appeared willing to drop their methods, with the suffragettes continuing to conduct militant acts and hunger-strikes; and the Government continuing to inflict harsh sentences for their actions, to conduct force-feeding and give temporary release. Despite the futility of the Government’s actions, it was only the outbreak of the First World War which provided a means of escaping this stalemate, with the WSPU immediately turning its energies to patriotic work and the Home Office releasing the last remaining women under amnesty.

Resources Used

- www.parliament, '1913 Cat and Mouse Act'

- Reviews in History, 'English Society and the Prison: Time Culture and Politics in the Development of the Modern Prison, 1850-1920'

- Spartacus Educational, 'Hunger Strikes'

- BBC News, 'Hunger Strikes: What can they achieve?'

- Women's History Review, “Culpable Complicity: the medical profession and the forcible feeding of suffragettes, 1909-1914”

- 'The Scottish Suffragettes', by Leah Leneman

- 'A Guid Cause: The Women's Suffrage Movement in Scotland' by Leah Leneman