250th Anniversary: 'A proper repository', General Register House 1774-2024

250th Anniversary: 'A proper repository', General Register House 1774-2024

An exhibition featuring the story of General Register House is now on show in the building's Adam Dome. Visit the free display to see many of the documents included in this article, and more!

Dates: 28 September – 29 November 2024, 9.00am-4.00pm

Venue: The Adam Dome, HM General Register House, 2 Princes Street, Edinburgh, EH1 3YY

This year marks the 250th anniversary of General Register House. An ever-present landmark in Edinburgh’s New Town on Princes Street. Despite the building’s prominence, many know nothing of the services it provides. Preserving and giving access to the records of the nation, General Register House is the first purpose-built repository in Britain and Ireland. It has a good claim to being one of the oldest purpose-built repositories still in use for its original function in the world. It holds and provides access to one of the most varied archive collections in Britain. However, before it existed, the records of Scotland had no permanent home.

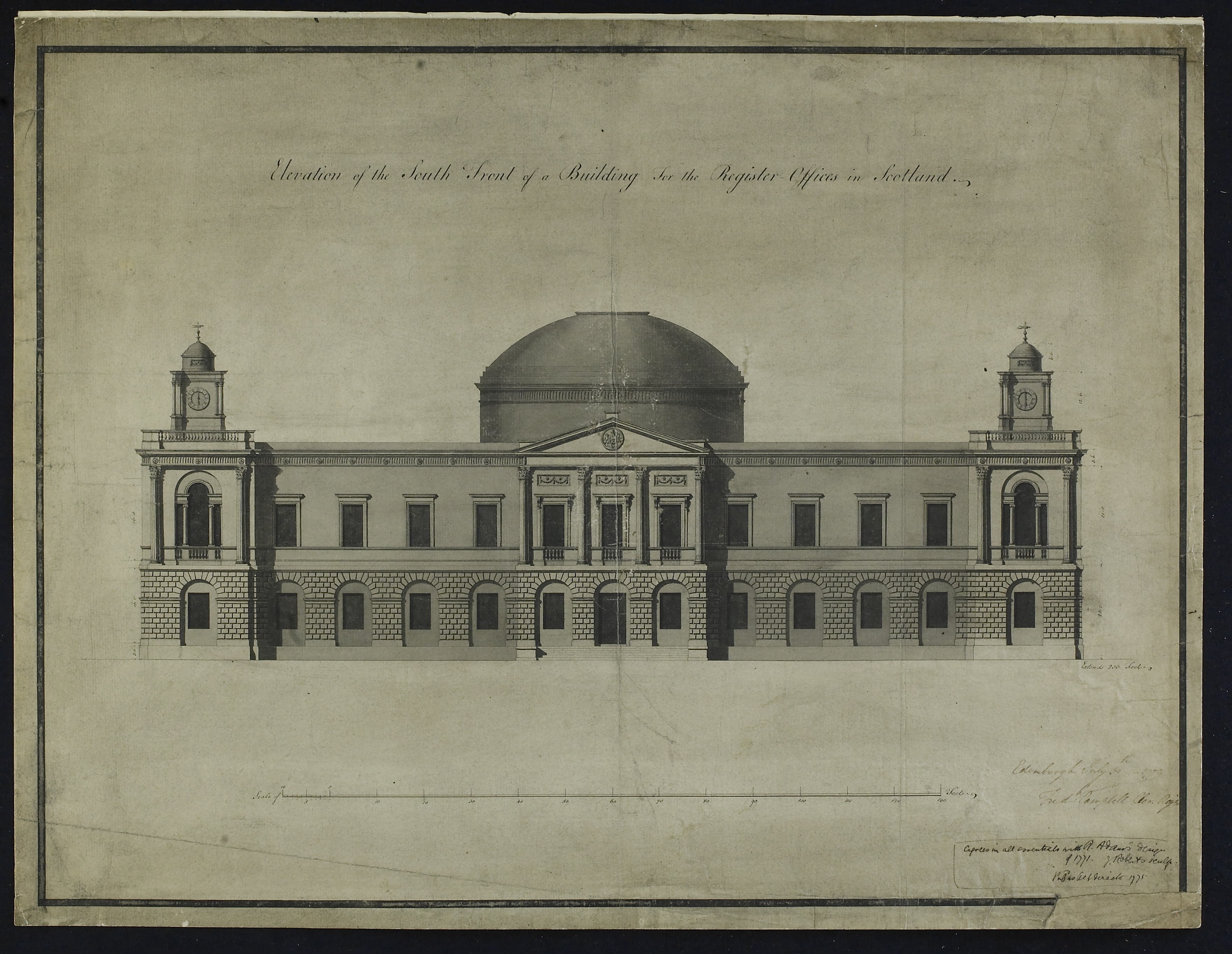

Contract drawing of General Register House, South front, 30 July 1772. The architects Robert and James Adam were appointed in 1772. The Adam brothers believed that a society could be judged by the quality and grandeur of its public buildings.

While the General Register House's design went through several stages, the principle façade, rotunda and four ranges of offices remained the same. Crown copyright, NRS, RHP6082/7.

Before General Register House

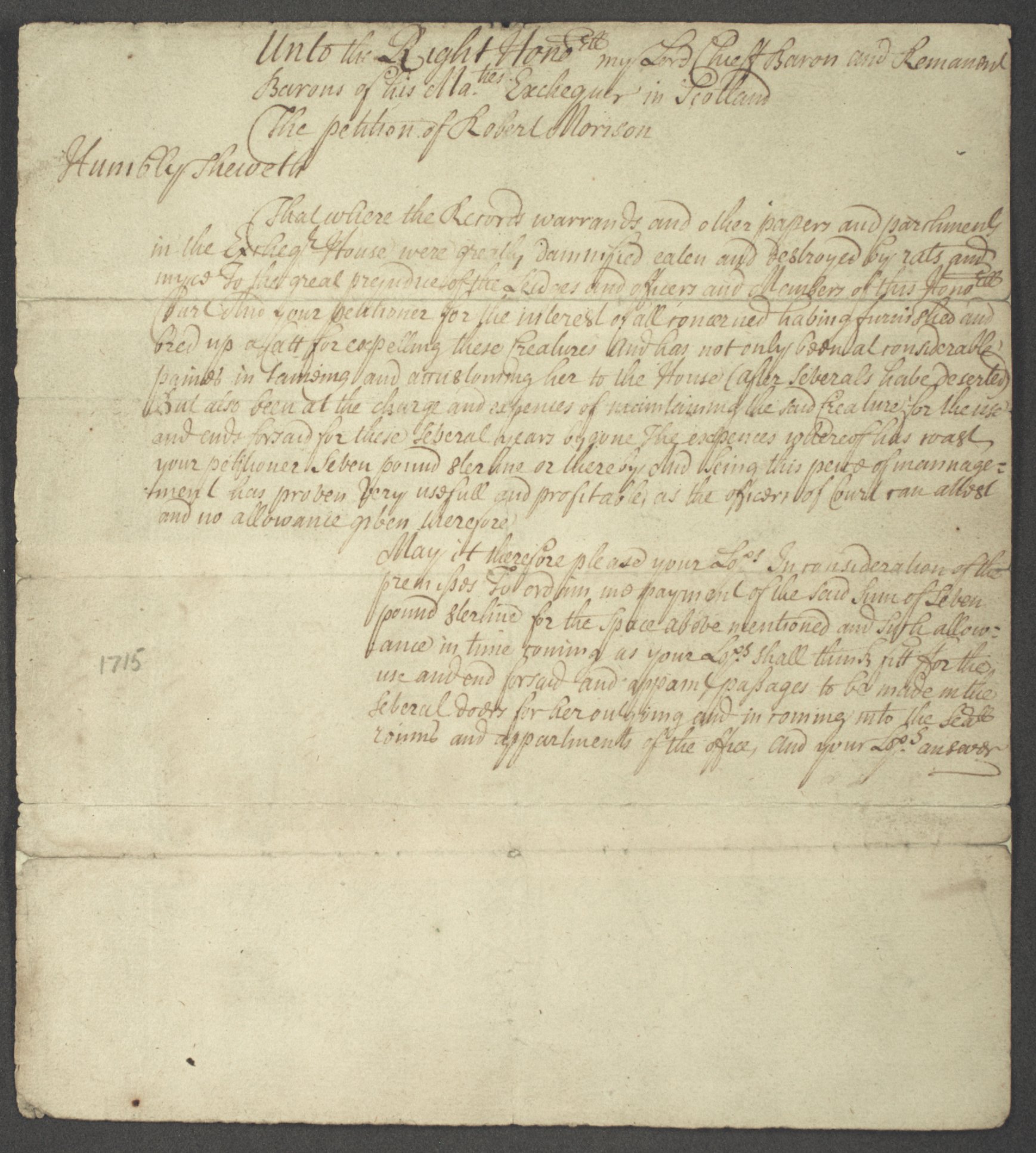

Despite two dispersals of the records, at the hands of Edward I of England in 1296 and Oliver Cromwell in 1650, the surviving records and a large quantity of government and legal documents had accumulated by the early 18th century. They were housed in various locations across Edinburgh. In the 1540s they were documented in a ‘register house’ at Edinburgh Castle, where the records remained until the 17th century. For a time, the records were moved to the Laigh Hall at Parliament House. There the walls ran with damp and the record officials had to pile up the latest documents on the floor. Evidence of the poor condition of the records is present in requests from the clerks working on them, including one from Robert Morison, who asked for money from the barons of the exchequer to ‘[breed] up a cat’ to control the vermin. It was agreed that a purpose-designed repository was desperately needed.

“… the records warrands and other papers and parchments in the Exchequer House were greatly damnified eaten and destroyed by rats and myce, to the great prejudice of the leidges…”

In order to stop the destruction of the records, Morison had ‘bred up a catt for expelling these creatures’ and was looking for recompense to cover the expenses of maintaining the said cat, in this case ‘seven pound sterline’. Papers of the Clerk family of Penicuik, Midlothian, NRS, GD18/2704. Courtesy of Sir Robert Clerk of Penicuik

Lord Frederick Campbell (1729-1816) by Henry Raeburn, c.1810. Crown copyright, NRS

The main credit for achieving a proper repository for the national archives of Scotland belongs to two men who held the office of the Clerk Register, James Douglas (1702-1768), 14th Earl of Morton, and Lord Frederick Campbell (1729-1816). In 1765, Morton obtained a royal warrant appropriating £12,000 from the forfeited Jacobite estates. This money was to be spent on purchasing ground and building a repository, and appointing trustees to administer the fund. Morton also conceived a design for a repository, which was engraved in 1767.

Warrant for £12,000. Crown copyright, NRS, E226/4/34

The front elevation for the Register Offices in Scotland, design by James Douglas, 14th Earl of Morton, and engraved by Robert Baldwin (1737-c.1810), printer in London, 1767. Crown copyright, NRS, RHP6082/38

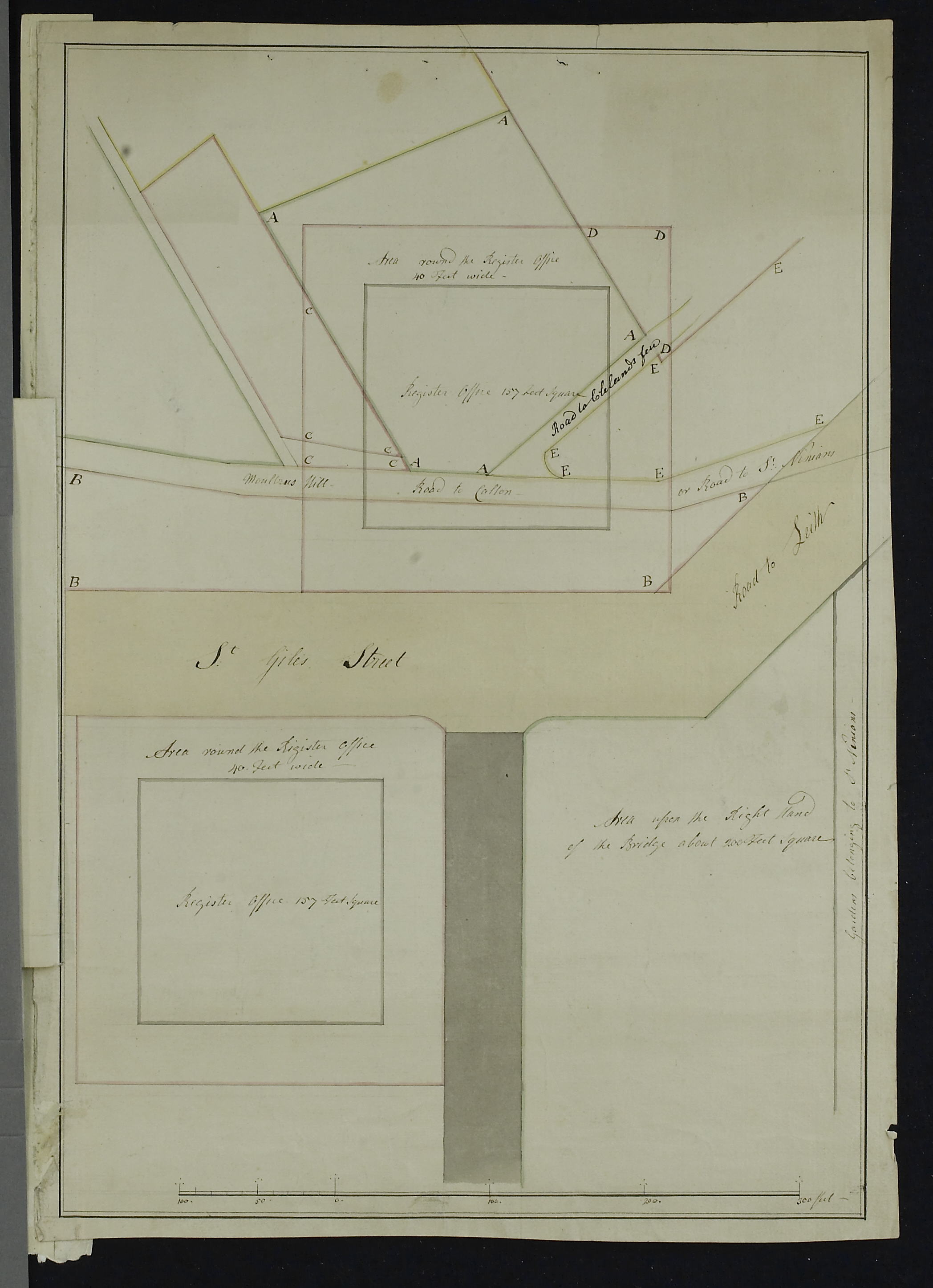

After an unsuccessful attempt to find a suitable spot in the Old Town, in 1769 the Trustees chose a site at the end of the North Bridge, then under construction. One part of the ground was owned by the Town Council, who agreed to provide their land gratis. Other property owners were consulted, and the land purchased by the Trustees.

The 1769 site plan shows the existing buildings and the division of land between different private owners. The ground marked A was given gratis by Edinburgh Town Council in August 1769 to the Building Trustees. On 21 September 1769, the Register Office Building Trustees accepted the land. Crown copyright, NRS, RHP6080/3

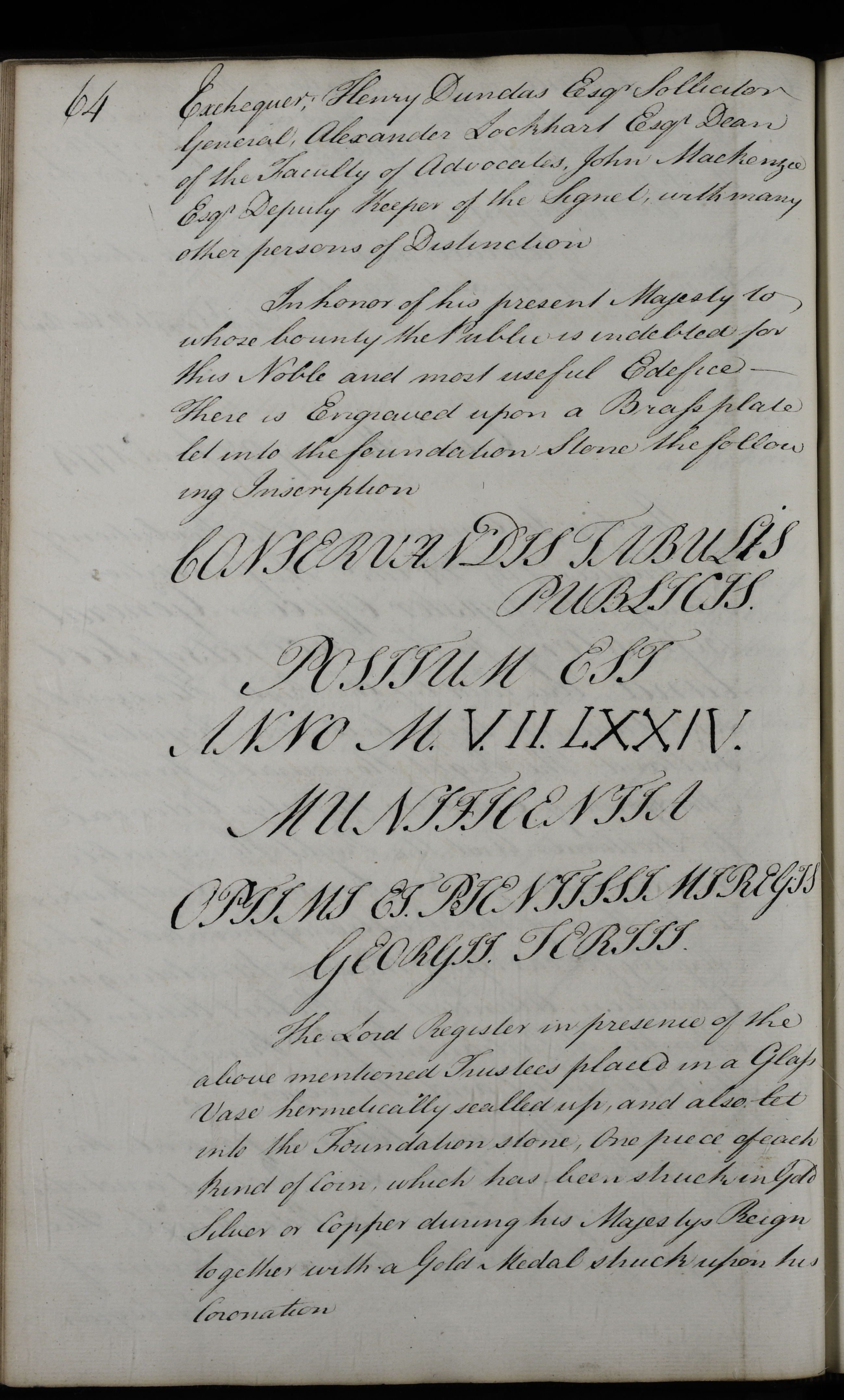

After the Earl of Morton’s death, a new plan for the building was drawn up by Robert and James Adam and accepted by the Register House Trustees in 1772. The foundation stone of General Register House was laid on Monday 27 June 1774 by Lord Frederick Campbell, Lord Clerk Register, Sir James Montgomery, His Majesty’s Advocate for Scotland, and Sir Thomas Miller, Lord Justice Clerk. Three of the building’s Trustees, in the presence of the architect, Robert Adam, who was MP for Kinross-shire at the time. The minutes record that the stone was set with an engraved brass plate with the following inscription:

CONSERVANDIS TABULIS PUBLICIS For keeping the public records

POSITUM EST Was placed

ANNO M.V.II LXXIV in the year 1774

MUNIFICENTIA By the munificence

OPTIMI ET PIENTISSIMI REGIS Of the best and most pious king

GEORGII TERTII George the Third

And that a sealed glass phial containing one with one of each kind of coin struck during George III’s reign, together with a gold medal commemorating his coronation was also inserted into the stone. Construction of the building proceeded under Robert Adam's direction.

The minutes record the foundation stone and its inscription. Crown copyright, NRS, SRO4/1 p64

'Most expensive pigeon-house in Europe'

The main feature of General Register House is the central dome or rotunda, now commonly referred to as the Adam Dome. Inspired by the Pantheon in Rome, it is Adam’s highest and largest surviving room and is designed to give access to the different parts of the building from one central space.

Robert Adam departed for Italy in 1754 to undertake a form of ‘grand tour’, reaching Rome in 1755. In this letter home, Adam writes on his studies with Clerisseau and the architecture of Rome, highlighting the Pantheon: “What pleased me most of all was the pantheon, of which the greatness, and simplicity of parts, fills the mind with extensive thoughts, stamps upon you the solemn, the grave & magistick, and seems to prevent all those ideas of gaity, or frolick which our modern buildings admitt of & inspire”. Papers of Clerk family of Penicuik , Midlothian, NRS, GD18/4765. Courtesy of Sir Robert Clerk of Penicuik

The plasterwork in the Dome was completed by a local Edinburgh-based plaster called Thomas Clayton. The antique-style shallow reliefs were purchased ‘off-the-peg’ in London and shipped to Edinburgh. The use of Scottish thistles, depicted in gold leaf, form the first band of ceiling decoration.

The Adam Dome ceiling. Crown copyright, NRS

For a time, this dome, and the building were roofless when, in 1778, funds ran out. For six years the building remained an empty shell and became a focal point of local criticism, leading the bookseller William Creech to describe it in 1783 as ‘the most expensive pigeon-house in Europe’. While some sneered at the roofless dome of General Register House others saw an opportunity. In 1784, James Tytler obtained permission to inflate his hot air balloon inside the roofless Dome. He went on to claim the statue of Britain’s first aeronaut (you can find out more about the life of James Tytler from the blog series: “The Sky’s the limit: James Tytler and balloon-mania in the archives”).

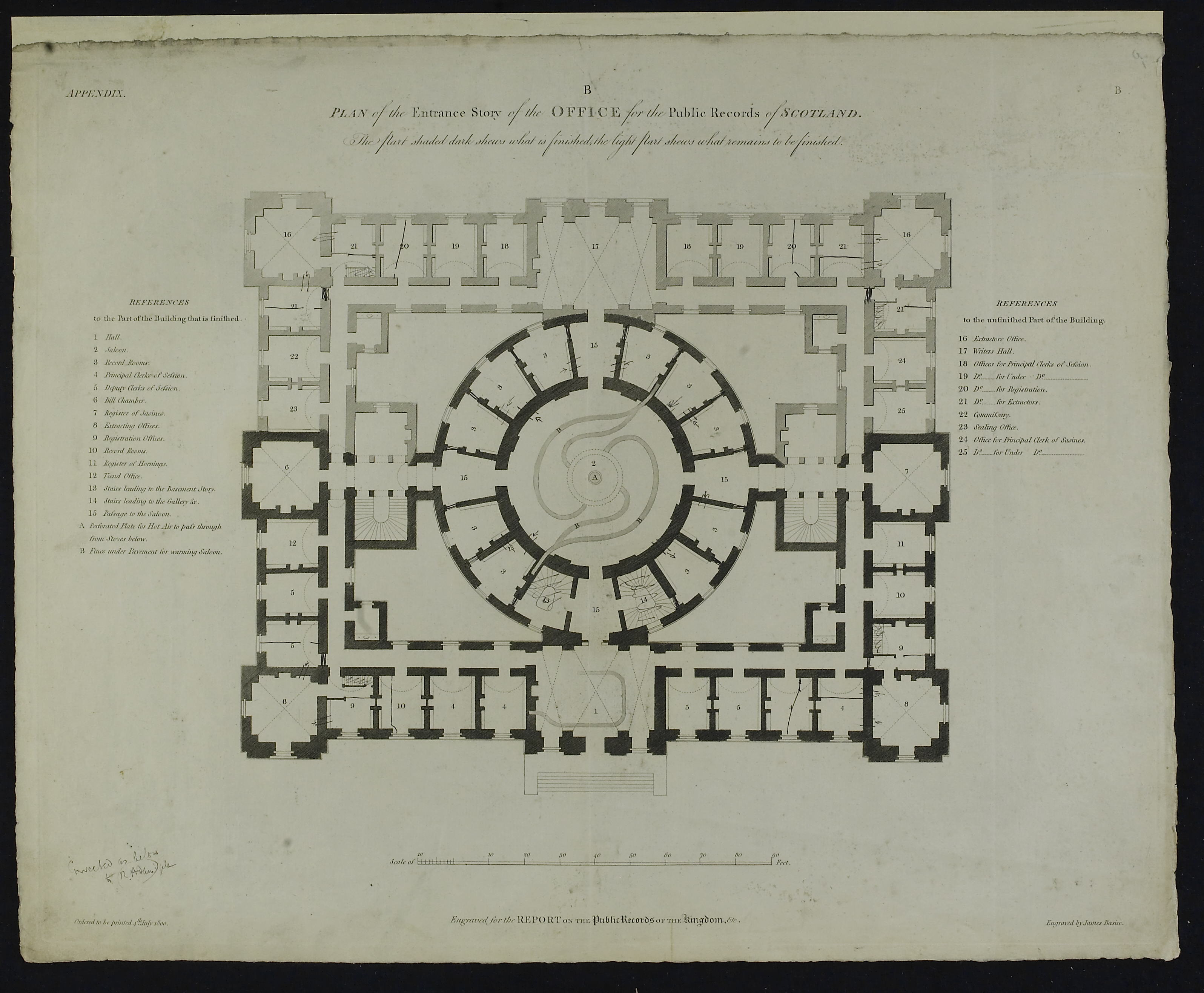

This plan shows the ground level of General Register house and the layout of the rooms in the 1800s. The dark shaded part of the plan shows the completed section of the building at that time. The light part reveals the areas of the plan not yet executed. The swirl marks in the centre, indicate the passage of hot air through flues or vents in the basement, into the central dome. While individual offices had fireplaces, heating the rotunda posed a challenge. Robert Adam solved this by constructing two flues in the floor which carried hot air from four furnaces in the basement which were kept constantly burning to protect the records from damp. Crown copyright, NRS, RHP6082/4

With a final grant of £15,000, work resumed in 1785. By 1789, most of the records and officials could be moved into their new home. When the contract for building General Register House was agreed in 1772 the building plan was reduced in scale, likely due to financial constraints, to only the front (south) façade, rotunda and the front half of the east and west ranges. Between 1822 and 1827 the whole building was completed to Adam's design externally but with internal modifications to plans by Robert Reid, HM Architect and Surveyor in Scotland. He also designed St George's Church in Charlotte Square (now the West Register House). The Matheson Dome, erected in 1871 on the north side of General Register House, was designed by Robert Matheson, Surveyor of HM Works. He also designed the General Post Office and the New Register House.

General Register House was built primarily as a record repository, but it was also designed to accommodate public offices concerned with the creation of records. Decades later, these offices moved out to other accommodation in order to create further space for records storage. The building is now occupied almost entirely by the National Records of Scotland. As regards the safe preservation of the records and their accessibility - the two prime considerations of archivists - General Register House remains a model of functional architecture. The construction of solid stone throughout, including stairs, floors and ceilings, guarantees high security against fire and the building is so planned as to allow any documents to be speedily fetched from any part to the search rooms.