Quintinshill Disaster 22 May 1915

Quintinshill Disaster 22 May 1915

The accident

At 6.45 on the morning of 22 May 1915, a troop train carrying soldiers of the 1/7th Battalion Royal Scots crashed into a stationary local passenger train near Quintinshill Junction on the Glasgow to Carlisle railway line, near Gretna in Dumfriesshire. The initial collision was caused by mistakes made by the railway signalmen. The northbound local train had been stopped in the path of the southbound troop train, which was carrying the battalion from Larbert to Liverpool. The Royal Scots were due to embark for Gallipoli. Minutes after the collision a northbound express train ploughed into the wreckage.

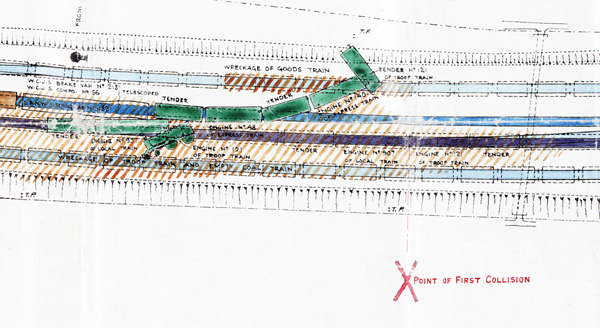

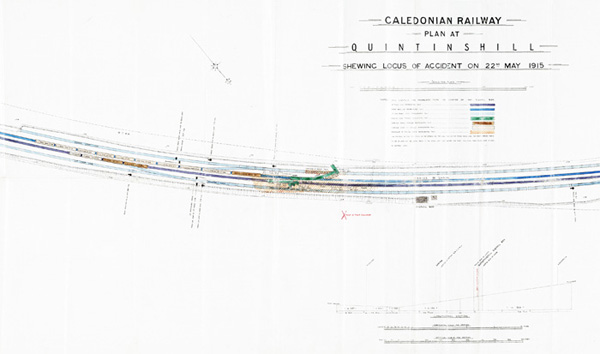

Detail of plan of accident site and position of trains at Quintinshill,

National Records of Scotland, RHP81457

Detail of plan of accident site and position of trains at Quintinshill,

National Records of Scotland, RHP81457

The lightly-constructed carriages of the troop train were badly damaged by the double impact, which caused many deaths and injuries. When the gas canisters on the troop train carriages caught fire many men were trapped and burned to death in the resulting conflagration. The deaths of 230 people make Quintinshill the biggest railway disaster to have occurred in Britain.

Soldier victims

Of the Royal Scots battalion three officers and 207 other ranks were killed or died from their injuries, and five officers and 219 other ranks were injured.

Testaments of officers and men who died in the crash can be found in the sheriff court records on ScotlandsPeople. In addition wills can be found in the series of Soldiers' Wills in ScotlandsPeople for the following men: Drummer 1625 John Inglis (D Company), Private 1731 John McDonald or Macdonald (A Company), Private 1688 Daniel Macnamara, Private 1641 Andrew Murray (A Company), Corporal 834 Alexander George Somerville, and Private 1956 John S Stewart (D Company). Two examples are given here.

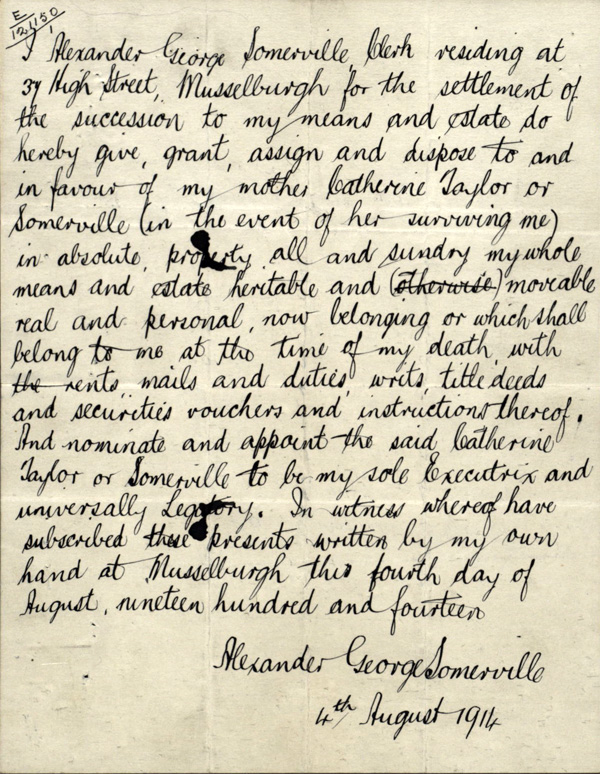

Corporal 834 Alexander George Somerville

Alexander George Somerville was born in 1891, the son of Robert, a Musselburgh cab driver, and his wife Catherine. Alexander had been working as a brewer's clerk since at least 1911, and had lived at 37 High Street with his parents. During peacetime he joined the 1/7th Battalion Scots, like many other young men in and around the town. By the time of the crash Somerville was a corporal.

General mobilisation on 30 July 1914 was followed by a declaration of war on 4 August, to which Somerville reacted by immediately writing his will, in which he left everything to his mother. He left the document at home, and after his death on 22 May 1915 it was officially recorded at Edinburgh Commissary Office. His estate amounted to a life insurance policy for £106 and a friendly society sum of £10.

Will of Alexander George Somerville,

National Records of Scotland, SC70/8/135/7

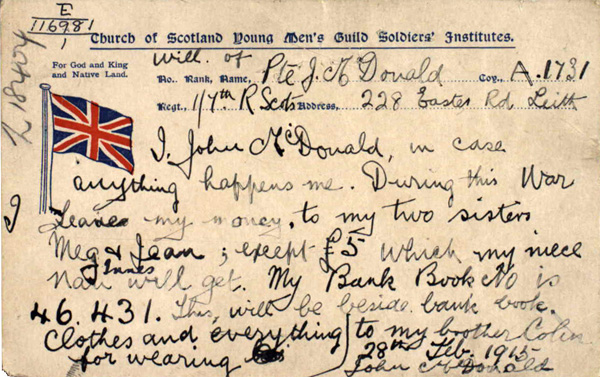

Private 1731 John McDonald

John McDonald or Macdonald of A Company, 1/7th Royal Scots, was a journeyman upholsterer, who lived with his family at 228 Easter Road, Edinburgh. His parents were dead and he was single, so in his will he provided for his older sisters Meg and Jean, his niece Nan (Agnes) Innes, and his brother Colin. He wrote his will on a card provided at one of the 'soldiers' institutes', premises provided by the Church of Scotland, where off-duty soldiers could relax.

Will of John McDonald, National Records of Scotland, SC70/8/177/34

Other victims

The driver and fireman of the troop train, and a sleeping car attendant on the express train died. Also killed were Rachael Nimmo and her infant son Dickson travelling from Newcastle on the local train, and on the express train Herbert Ford, a Scottish engineer, and five other passengers, of whom four were not identified. Other passengers on the express train who were killed included three army and two naval officers.

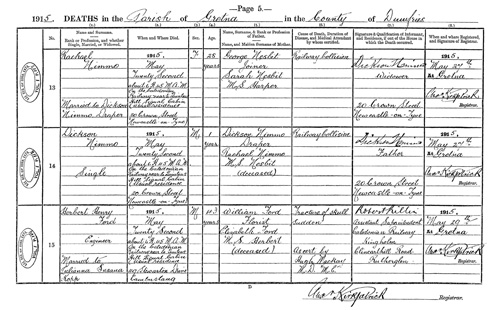

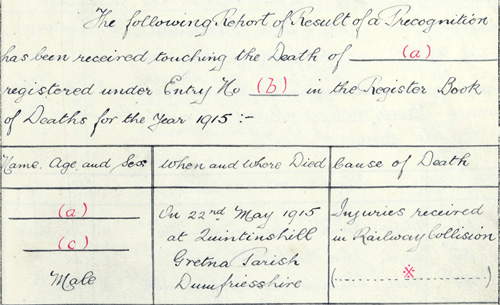

Deaths of Rachel and Dickson Nimmo, and Herbert Ford,

National Records of Scotland, Register of Deaths, 1915, 827, nos 13-15

Registration of deaths

The deaths of all those who died at the scene of the accident were recorded in the register of deaths for Gretna, starting with the civilian victims on 23 and 29 May. From 29 May until 29 November 1915 the registrar registered the deaths of the Royal Scots. The informant signing each entry was Captain James Noel Bertram, whose home address was given, perhaps to avoid disclosing the battalion's headquarters. The three army officers and two naval personnel who were travelling on the express train were also registered.

After the Fatal Accident Inquiry at Dumfries on 4 November 1915, the Procurator Fiscal submitted his findings into the deaths (the result of his precognitions and the jury's verdict) during November and December 1915. The finding that the deaths resulted from 'Injuries received in Railway Collision' was recorded by the local registrar in individual entries in the Register of Corrected Entries (RCE) for each of the civilian deaths. In effect this amended the simple cause 'Railway Collision' that had been entered in almost all entries in the Register of Deaths. The same amendment was applied to all the Royal Scots and other servicemen, but unusually they were listed in a group entry in the RCE on 5 February 1916. This group entry underlines both the scale of the tragedy and the terrible circumstances in which the many soldiers died: those whose bodies were unidentifiable are marked with a red dotted cross. This list of Royal Scots soldiers does not include those who died of their injuries in England, having been taken to Carlisle for treatment.

Detail of Register of Corrected Entries,

National Records of Scotland, Gretna, 827, vol 1 pp.124-129

Register of Corrected Entries for soldiers' deaths in the Quintinshill Disaster (pdf)

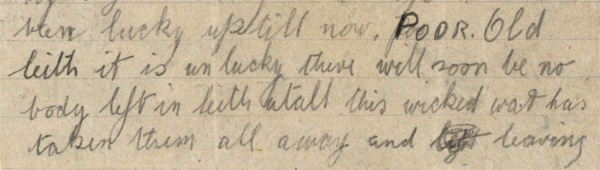

Reactions to the tragedy

Newspapers reported the tragedy in Britain, and soon soldiers overseas learned of the terrible events. Private James Tracey, serving with the 13th Hussars on the Western Front, was deeply saddened by the deaths of so many of his Leith school friends. Just one week after the crash he wrote home to his mother Bridget in Leith: 'you have no idea how sorry I feel for those poor helpless young fellows who died, pinned beneath the wreckage... Giving my deepest sympathy to all the survivors at home.' Tracey was killed in action six weeks later on 12 July 1915.

Detail of letter from Private James Tracey to his mother, 29 May 1915,

National Records of Scotland, SC70/8/136/15

Transcription of James Tracey's letter, SC70/8/136/15 (pdf)

Investigations and High Court trial

The Board of Trade carried out an investigation immediately, and an inquest into the deaths began at Carlisle on 25 May. It concluded that the signalmen James Tinsley and George Meakin were responsible for the manslaughter of those who died in the collisions.

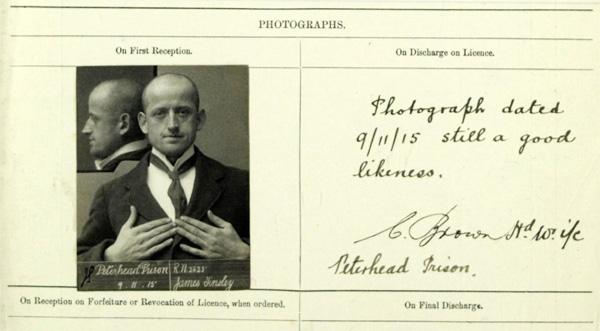

At the High Court trial in Edinburgh on 14 September 1915 Tinsley and Meakin were held responsible for their failure to follow railway company rules and regulations. They were convicted of culpable homicide arising from gross neglect of duties. Meakin was sentenced to eighteen months imprisonment, while Tinsley, who bore the greater share of blame, was committed to Peterhead prison for three years' imprisonment with hard labour.

The conviction of the two men focussed attention on their individual failings. On 4 November a Fatal Accident Inquiry at Dumfries Sheriff Court examined the circumstances of the deaths of the three railwaymen who were killed (SC15/27/1915/9). It exposed weaknesses in the Caledonian Railway Company's practices in supervising and carrying out signalling, but concluded that the signalmen were to blame for the crash. Other contributory factors, such as the pressures on the railway network from the high priority accorded to military trains, and technical deficiencies in the rolling stock, received little or no scrutiny in the official investigations.

Detail of prisoner's record of James Tinsley ,

National Records of Scotland, HH15/10

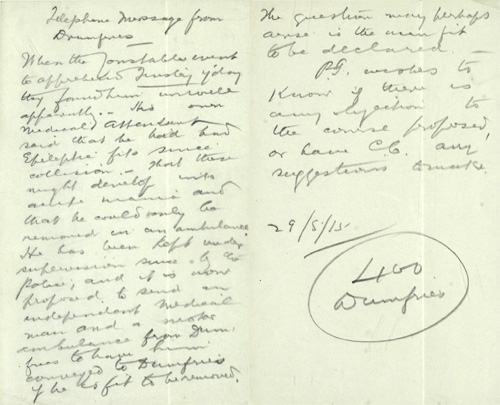

Evidence in the Crown Office precognition reveals that when the Dumfries police arrested Tinsley on 28 May, a doctor pointed out that he suffered from epilepsy. His condition may have contributed to his forgetfulness at the time of the accident.

Note about James Tinsley's epilepsy,

National Records of Scotland, AD15/15/29/1/1/2-3

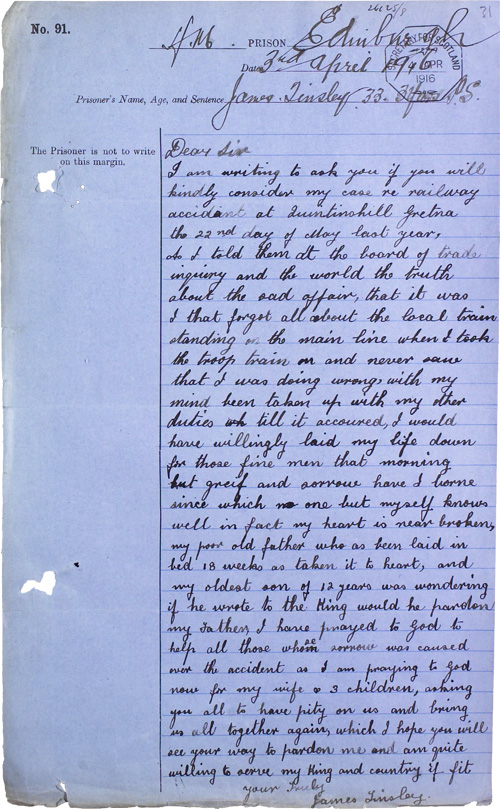

After the trial successive Secretaries of State for Scotland came under pressure from J H Thomas of the National Union of Railwaymen, and sections of public opinion, to have Tinsley's and Meakin's sentences reduced, or even for them to receive a royal pardon. Tinsley himself petitioned the Secretary of State on 3 April 1916. He was eventually released one year early, on 15 December 1916, on the same day that Meakin was released on completing his sentence.

Image of Tinsley's petition to the Secretary of State for Scotland, 3 April 1916,

National Records of Scotland, HH60/316/8/31

Records in the National Records of Scotland

National Records of Scotland makes available a wealth of official sources that throw light on the Quintinshill railway disaster. Statutory records of births, marriages and deaths, censuses, and wills and testaments can be searched online at ScotlandsPeople. Other records can be searched on our online catalogue and guides to classes of records and subjects include railway records, maps and plans, High Court and Crown Office records, Fatal Accident Inquiries and Scottish Office records.