Battle of Jutland 1916

Battle of Jutland 1916

During the First World War Britain’s Grand Fleet dominated the North Sea from its bases at Scapa Flow in Orkney, Invergordon on the Cromarty Firth and Rosyth on the Forth, while smaller forces operated from east coast ports in England. At the Battle of Jutland on 31 May – 1 June 1916 Admiral Jellicoe’s Battle Fleet joined forces with the Battlecruiser Fleet commanded by Vice-Admiral Beatty.

At Jellicoe’s disposal at Scapa and Invergordon were 24 battleships, three battlecruisers, eight heavy cruisers, eleven light cruisers, and three flotillas of destroyers. Beatty’s Battlecruiser Fleet at Rosyth was built around three squadrons of battlecruisers, fast and heavily-armed but less well protected than battleships. In place of the 3rd Battlecruiser Squadron which had been detached to Scapa for gunnery practice, in May 1916 Beatty had the 5th Battle Squadron of four fast battleships to complement his six serviceable battlecruisers. The remainder of the Rosyth force consisted of twelve light cruisers in three squadrons, and three destroyer flotillas.

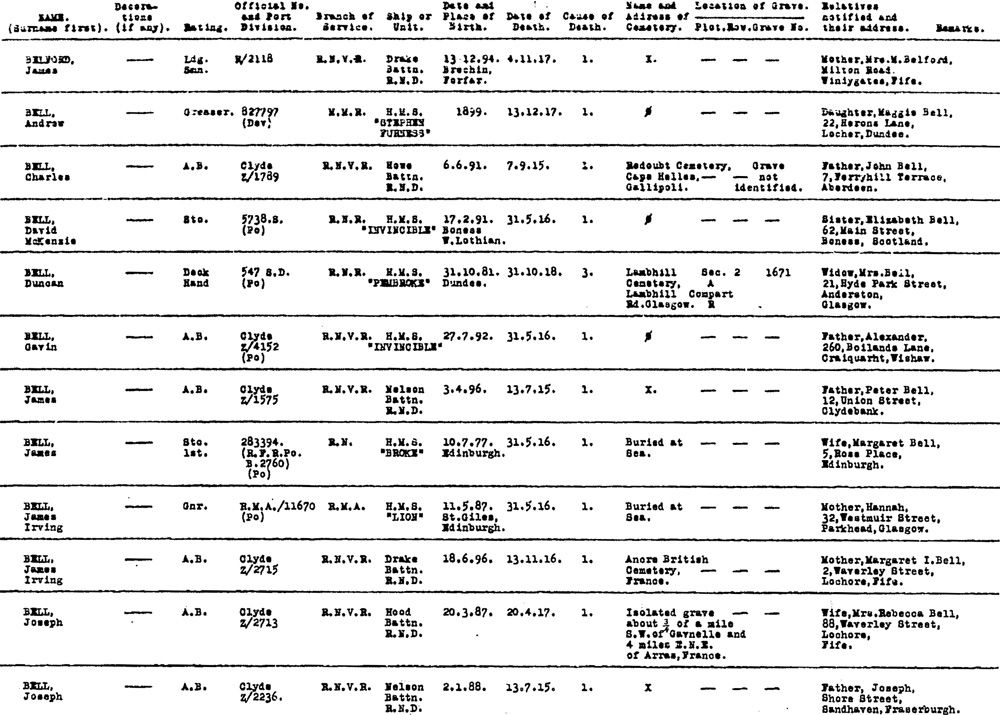

HMS ‘Barham’ and the destroyers ‘Mons’ (left) and ‘Medusa’,

being fitted out at Clydebank, July 1915

Upper Clyde Shipbuilders Collection, Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland, UCS1/116/16/38

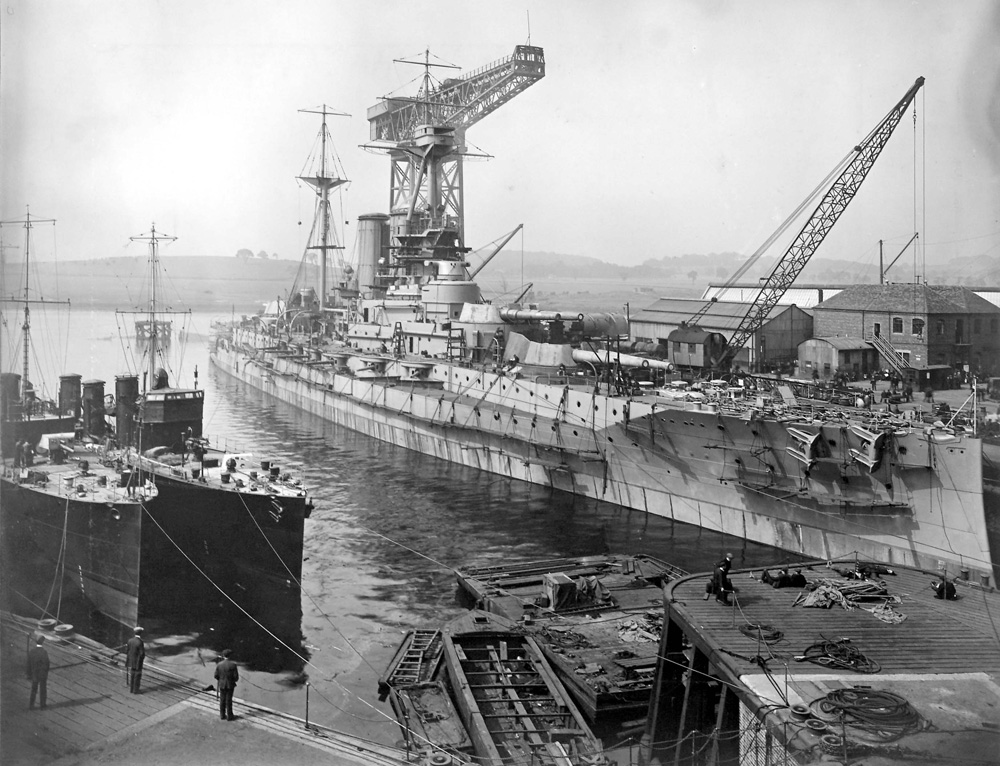

Not only was the majority of Britain’s naval capacity in home waters based in Scotland, but of 150 ships that fought at Jutland, no fewer than 63 (over 40%) had been constructed in shipyards on the River Clyde. However, only one-fifth of 28 dreadnought battleships were Clyde-built. ‘Colossus’ with 12 inch guns was begun at Scott’s yard in 1909 and completed in 1911. ‘Conqueror’, ‘Ajax’ and ‘Benbow’, all armed with 13.5 inch guns, were completed between 1912 and 1914. These four served in Jellicoe’s battle squadrons. The latest dreadnoughts were ‘Barham’ (John Brown & Co, 1915) and ‘Valiant’ (Fairfield’s, 1916). Mounted with 15 inch guns, they served in the 5th Battle Squadron.

HMS ‘Valiant’, the Fairfield-built Queen Elizabeth class battleship

of the 5th Battle Squadron, passing Clydebank, February 1916.

Upper Clyde Shipbuilders Collection, Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland, UCS1/118/Old Red/326/5

Of the nine British battlecruisers at Jutland, four were Clyde-built. Battlecruiser production began with the laying down of ‘Inflexible’ and ‘Indomitable’ in early 1906, and continued with ‘New Zealand’ and ‘Australia’ (which was absent from Jutland). The latest to be completed was ‘Tiger’ in October 1914.

Clyde yards also built nine cruisers, including the Cambrian class light cruiser ‘Canterbury’, which was one of the most recent ships to join the fleet, having been completed at Clydebank earlier in May 1916. At Jutland ‘Canterbury’ fought alongside ‘Chester’ as a scout for Jellicoe’s fleet, but avoided the catastrophic damage suffered by the latter.

HMS ‘Canterbury’ with splinter mats fitted around her bridge, and a 4-inch gun.

Upper Clyde Shipbuilders Collection, Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland, UCS1/118/435/11

Among the pre-war destroyers built at Clydebank was ‘Acasta’. At the height of the Battle of Jutland as part of the 4th Destroyer Flotilla she courageously pressed home a torpedo attack on the German battlecruiser ‘Seydlitz’. Of the twelve destroyers completed at John Brown’s between the outbreak of war and Jutland, ‘Mons’ and three others fought at Jutland. No fewer than 43 of the Navy’s destroyers in the battle had been constructed at Fairfield’s, John Brown & Co, Denny’s, Yarrow’s, Beardmore’s, Harland and Wolff and Alexander Stephen’s.

Launch of HMS ‘Acasta’ at John Brown & Co’s yard, 1912

Upper Clyde Shipbuilders Collection, National Records of Scotland, UCS1/118/412/1

The Battle of Jutland began with an encounter off the Danish coast between the battlecruiser forces of Vice-Admiral Hipper and Vice-Admiral Beatty, during which the Germans rapidly gained the upper hand. The battlecruiser HMS ‘Lion’, Beatty’s flagship, was quickly hit and lost two of her eight 13.5 inch guns when a turret was put out of action. Only quick-thinking action prevented an explosion in her magazine. During the battle she lost 99 dead and 51 wounded. Her wireless transmitter was also damaged, which hindered Beatty’s command and communications with his fleet during the battle.

Vice-Admiral David Beatty (hands in pockets) on the forecastle of HMS ‘Lion’,

with her Captain, A E Chatfield (fourth from right), and other officers, 1916.

National Records of Scotland, MW12/33

Inadequate flash protection of the magazines and the way that ammunition was handled in order to maximise the rate of fire, contributed to the loss of three battlecruisers at Jutland, as did their weaker armour. The German battlecruisers delivered more accurate fire from generally smaller calibre guns, and the power of their armour-piercing shells against the relatively light armour of the British battlecruisers was demonstrated again when HMS ‘Indefatigable’ of the 2nd Battlecruiser Squadron was hit by two salvoes from ‘Von der Tann’. The second salvo penetrated her armour, causing her to blow up, with the loss of all but two of her 1,107 crew, witnessed helplessly by ‘New Zealand’, her sister ship in the squadron. ‘New Zealand’ survived Jutland, but owing to poor gunnery she contributed less than the potential of her eight 12 inch guns. The third sister ship ‘Australia’ was perhaps fortunate to be in dock for repairs after a collision.

HMS ‘New Zealand’ passing Clydebank after completion at Fairfield’s Govan yard in 1912

Upper Clyde Shipbuilders Collection, National Records of Scotland, UCS1/118/Old Red/25/1

As the two fleets steamed rapidly on parallel courses to the south east, accurate salvoes from Hipper’s battlecruisers continued to damage Beatty’s. The British predicament was eased by the belated arrival of the battleships of 5th Battle Squadron. HMS ‘Barham’ led ‘Valiant, ‘Warspite’ and ‘Malaya’ in pouring fire from their 15 inch guns onto the rear German battlecruisers, forcing them into avoiding action.

An after turret on the battleship ‘Barham’ being fitted with 15-inch guns at

John Brown & Co’s yard in May 1915, before her completion in August.

Upper Clyde Shipbuilders Collection, Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland, UCS1/118/424/231

Despite the damage being inflicted on several of the German ships, the battlecruisers ‘Derfflinger’ and ‘Seydlitz’ were able to concentrate their fire on ‘Queen Mary’ of the 1st Battlecruiser Squadron. A few salvoes were enough to cause her to explode, capsize and rapidly sink, taking with her 1,226 officers and men.

HMS ‘Tiger’, which fought with ‘Queen Mary’ in the

1st Battlecruiser Squadron, during her trials, October 1914.

Upper Clyde Shipbuilders Collection, Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland, UCS1/118/418/160

During this phase of the battle Beatty deployed his destroyers, which clashed with German torpedo boats. Soon he sighted Admiral Scheer’s larger fleet to the south which was making all speed to support Hipper and trap Beatty. The British fleet now changed course northwards to lure Scheer and Hipper towards Jellicoe’s fleet which was now approaching rapidly. Beatty's battleships were late in turning away and lucky to escape with non-critical damage, but they continued to strike the chasing German battleships as they raced north. Scheer’s advancing ships sank two of Beatty’s destroyers, and ‘Defence’, a cruiser in the outer screen of Jellicoe’s fleet, which went down with over 900 men.

The light cruiser HMS ‘Castor’, flagship of 11th Destroyer Flotilla,

which was to lose twelve men at Jutland, passing Clydebank, February 1916

Upper Clyde Shipbuilders Collection, Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland, UCS1/118/Gen 372/2

By now the 3rd Battlecruiser Squadron in advance of Jellicoe’s fleet was displaying superior gunnery as it engaged with ‘Lützow’ and ‘Derfflinger’. All the British battlecruisers were now scoring hits on Hipper’s squadron of five. But a shell from ‘Derfflinger’ penetrated a turret on HMS ‘Invincible’, which was instantaneously destroyed when her two midships magazines blew up. She lost 1,026 officers and men. ‘Invincible’ had fought alongside ‘Inflexible’ at the Battle of the Falkland Islands in 1914.

Despite this disaster and the poor visibility, Jellicoe handled his overwhelming force of battleships brilliantly. His capital ships were now pounding Scheer’s fleet, which turned away and was lost to view in the mist before Scheer commanded his ships to turn again for the so-called ‘death ride’, a desperate attack aimed at breaking the better-positioned British fleet. The German dreadnoughts came off worse, and turned away again to the west. However, Jellicoe also took avoiding action against the German torpedo attack now launched against him, and in turning away lost contact with Scheer’s heavy ships. As night fell, Jellicoe tried to cut Scheer off from his home ports, but intermittent skirmishes and sightings through the night did not lead to the hoped-for final contact. The German fleet, including several crippled battlecruisers, escaped Jellicoe’s trap.

Jellicoe’s and Beatty’s fleets returned to their bases. Damaged vessels mostly went to Rosyth, where repairs soon restored much of the British fleet’s strength. The heavily-damaged ‘Warspite’ and the less damaged ‘Tiger’ were still receiving attention when King George V visited Rosyth on 15 June 1916 to inspect the fleet. He thanked the crews, “mourning with them the loss of the brave men who had fallen.” (‘Dundee Evening Telegraph’, 19 June 1916)

King George V addressing the company of HMS ‘Warspite’ at Rosyth, 15 June 1916

National Records of Scotland, MW12/29

Detail of photograph of King George V addressing

the company of HMS ‘Warspite’ at Rosyth, 15 June 1916

National Records of Scotland, MW12/29

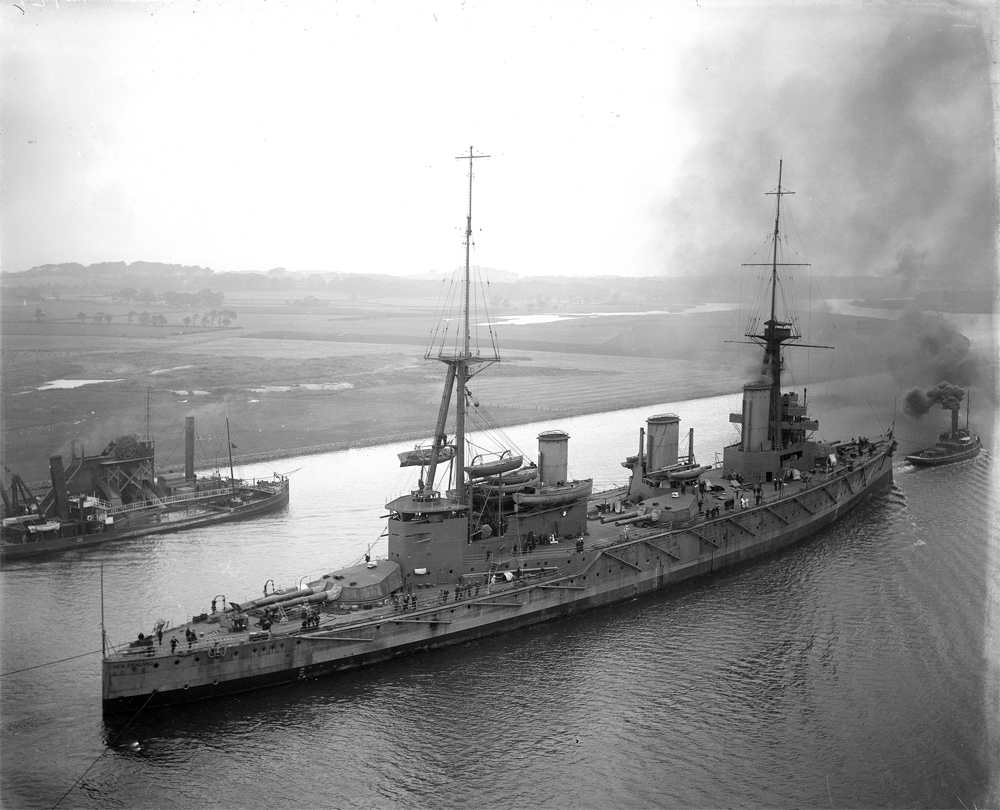

Seamen’s lives were lost on a staggering scale at Jutland. The German dead amounted to 2,551, but British losses were 6,097, of whom more than half died on the three battlecruisers that were sunk. The battle affected some communities as badly as the worst land battles of the war. When the news of the sinking of the battlecruisers reached the small burgh of Wick in Caithness, the blinds of many houses were drawn in Pulteneytown, the fishermen’s quarter. No fewer than eleven local men were lost on ‘Invincible’ and four on ‘Queen Mary’. In peacetime most were fishermen and all were seamen in the Royal Naval Reserve who were called up in 1914 to man the warships. All but two were married, and they left 13 widows and 33 fatherless children. The loss of 15 sailors on a single day compares with the 38 others from the town who were lost at sea at other times during the war. The 6,000 British deaths at Jutland can be compared to overall British losses of 44,000 during the war at sea.

Fifteen names of the 53 naval men on Wick’s war memorial are of men lost

at Jutland on ‘Invincible’ and ‘Queen Mary’

National Records of Scotland

After their return to base crews were granted leave, while the many wounded were taken to the naval hospitals at South Queensferry, and also to the Royal Infirmary in Edinburgh where on 16 June the King spoke to all the hundred or so wounded men reported to be receiving treatment. HMS ‘Tiger’ had lost 20 dead at Jutland, to which was added another name a month later. Having survived the battle, on 1 July Leading Stoker James Quinn was involved in a motor bus accident, contracted gangrene and died four days later in hospital at South Queensferry. The twenty six year-old from Dundee was buried at Dalmeny nearby.

Deaths of four Scottish sailors at Jutland among others in the Royal Navy returns of deaths

National Records of Scotland, Minor Records, vol. 145, p.19

As well as restoring damaged warships to battle readiness, the Navy replaced lost battlecruisers and other ships and maintained its overall superiority over Germany’s fleet. For example, on the Clyde the battlecruisers ‘Repulse’ and ‘Renown’ were nearing completion as Jutland was fought. These sister ships, each armed with six 15 inch guns went into active service in August and September respectively. The lesson from Jutland of the vulnerable deck armour of the British battlecruisers led to the fitting of additional armour plate to ‘Repulse’ during winter 1916-17. It also influenced the heavier turret armour of HMS ‘Hood’ and other Admiral class battlecruisers that were begun in 1916.

The conning tower and forward turrets with 15 inch guns of

HMS ‘Repulse’ at John Brown & Co’s Clydebank yard, August 1916

Upper Clyde Shipbuilders Collection, Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland, UCS1/118/443/295

At Jutland several factors, including poor signalling and communications in Beatty’s fleet and the misty sea conditions, meant that the British Grand Fleet missed the chance to inflict heavier losses on the German High Seas Fleet. The Royal Navy suffered the humiliating loss of fourteen ships, including three of its vaunted battlecruisers, to effective German gunnery. British shells were less effective because they mostly exploded on impact rather than penetrating armour plate. Nevertheless the damage done to the German High Seas Fleet was very considerable. In addition to the loss of eleven ships, including the battlecruiser ‘Lützow’, several capital ships spent months under repair, while the British fleet was ready for action immediately.

After Jutland Germany made the most of its lighter losses of men and ships, while in Britain the Navy was criticised by many for its apparent failures. It was reported that a ‘Daily Mail’ journalist in search of news was interviewed at the Admiralty by Captain Reginald Hall, Director of Intelligence Division (DID), who told him he was making a fool of himself, as the Navy had done very well. ‘ “How do you make that out?” said the reporter. “‘Well”’ said the DID, “if I kick you out of this room, which I shall do presently, and you can’t get back again, isn’t that a victory for me even if I get a black eye in the process.” ’ (National Records of Scotland, GD433/2/357, pp.8-9).

The strategic value of the Battle of Jutland became apparent: the Royal Navy achieved its aim of containing the German naval threat, and deterred German warships from all but minor actions in the North Sea. A New York newspaper assessed Jutland succinctly: ‘The German Fleet has assaulted its jailer, but it is still in jail.’ After the battle the Royal Navy’s continuing blockade of German ports led to severe shortages of imported foods and war materials. The Navy also overcame the new threat from German submarines against Atlantic supply lines. Both these achievements contributed hugely to the Allied victory in 1918.

Further sources:

More images of Clydebank warships can be found in our Image Gallery and a feature on German naval espionage before the First World War.

Ian Johnston, ‘A Shipyard at War’ (Barnsley, 2014) and ‘Clydebank Battlecruisers : Forgotten Photographs from John Brown’s Shipyard’ (Barnsley, 2011); Michele Cosentino and Ruggero Stanglini, ‘British and German Battlecruisers: Their Development and Operation (Barnsley, 2016); Geoffrey Bennett, ‘Naval Battles of the First World War’ (London, 1968); Ally Budge, ‘Voices in the Wind: Caithness and the First World War’ (Wick, 1996).