The sinking of H M Yacht Iolaire, 1 January 1919

The sinking of H M Yacht Iolaire, 1 January 1919

In the early hours of New Year’s Day 1919 HMY ‘Iolaire’ struck rocks off Holm Point as the vessel approached Stornoway harbour on the Isle of Lewis. Records in NRS provide evidence of the lives of many of the official total of 205 men who lost their lives in the wreck of the Iolaire on 1 January 1919, and the impact the tragedy had on the community of the Island of Lewis. Few families there did not experience the loss of relatives or friends among the 184 Lewis men who died, most of whom had served in the Royal Naval Reserve (RNR). The bereaved also included some of the 3,100 Lewis men who had served in the wartime RNR. Most of them survived to enjoy the peace, but some lost fathers, uncles, brothers or cousins on the Iolaire.

Biastan Holm (the Beast of Holm) rocks in the approach to Stornoway harbour, 1897. National Records of Scotland, IRS126/651

In December 1918 Iolaire was a lightly-armed steam-powered yacht in the Royal Navy’s Auxiliary Patrol force, based at Stornoway. It had been hired in 1915 by the Admiralty (pennant no. 065) to augment the thousands of small vessels that served in home and foreign waters. It was built as a private yacht in 1881 at Ramage and Ferguson’s shipyard in Leith. In November 1918 it was renamed Iolaire, having previously carried the name Amalthaea, and before that, Iolanthe and Mione.

The Admiralty yacht HMY Iolaire under the name 'Amalthaea'

Image credit: Ness Historical Society, via Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain)

Among the scattered records in NRS that relate to the Iolaire disaster, the testaments and other sheriff court records provide precious evidence of individual circumstances, and highlight some of the social conditions on Lewis that shaped the lives of some of those who perished in the wreck. A little-known series of records shows how islanders appealed against conscription during the First World War.

Some islanders' stories

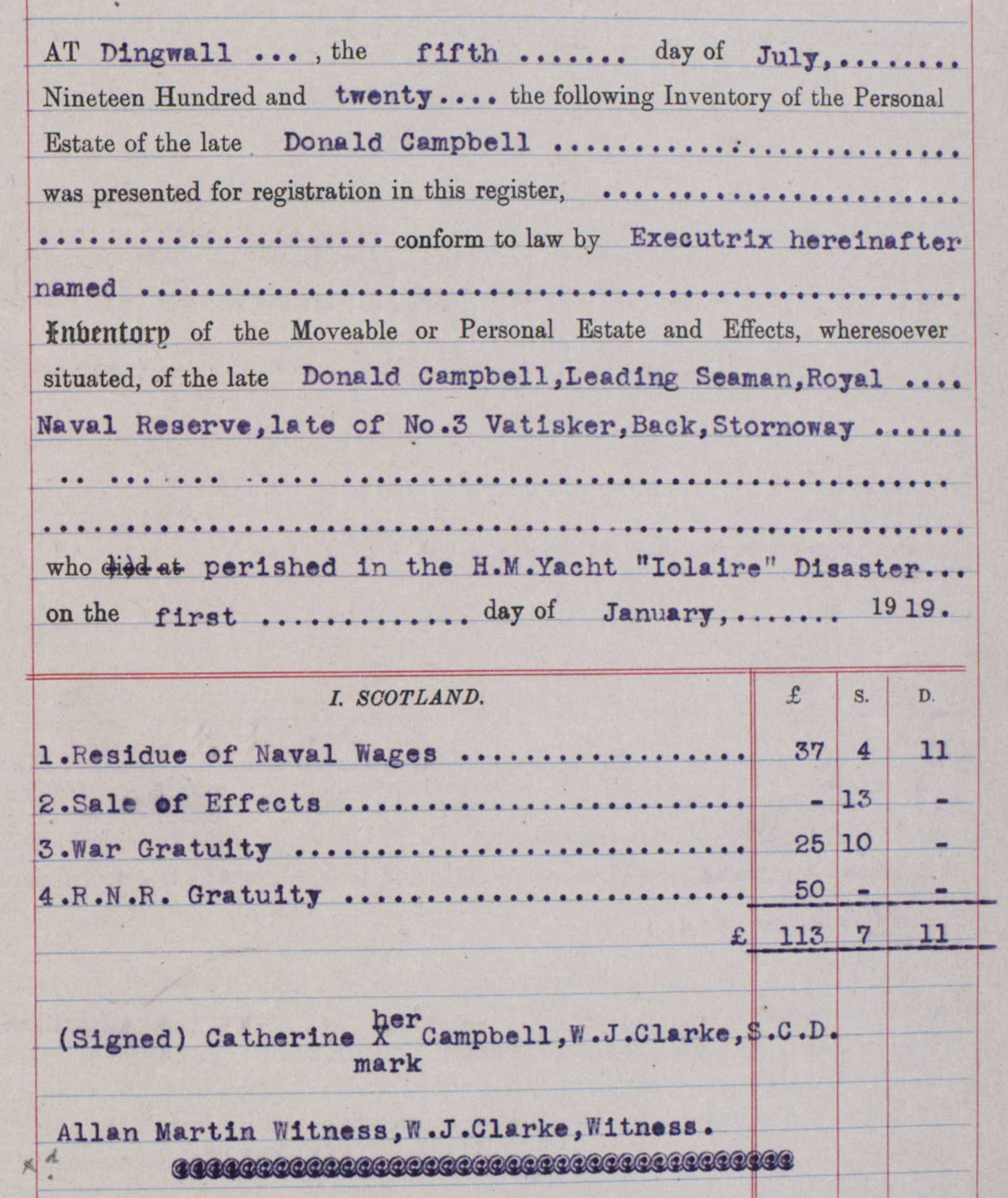

Details of inventory of estate of Donald Campbell, RNR, who died on the Iolaire. National Records of Scotland, SC25/44/31, p.685

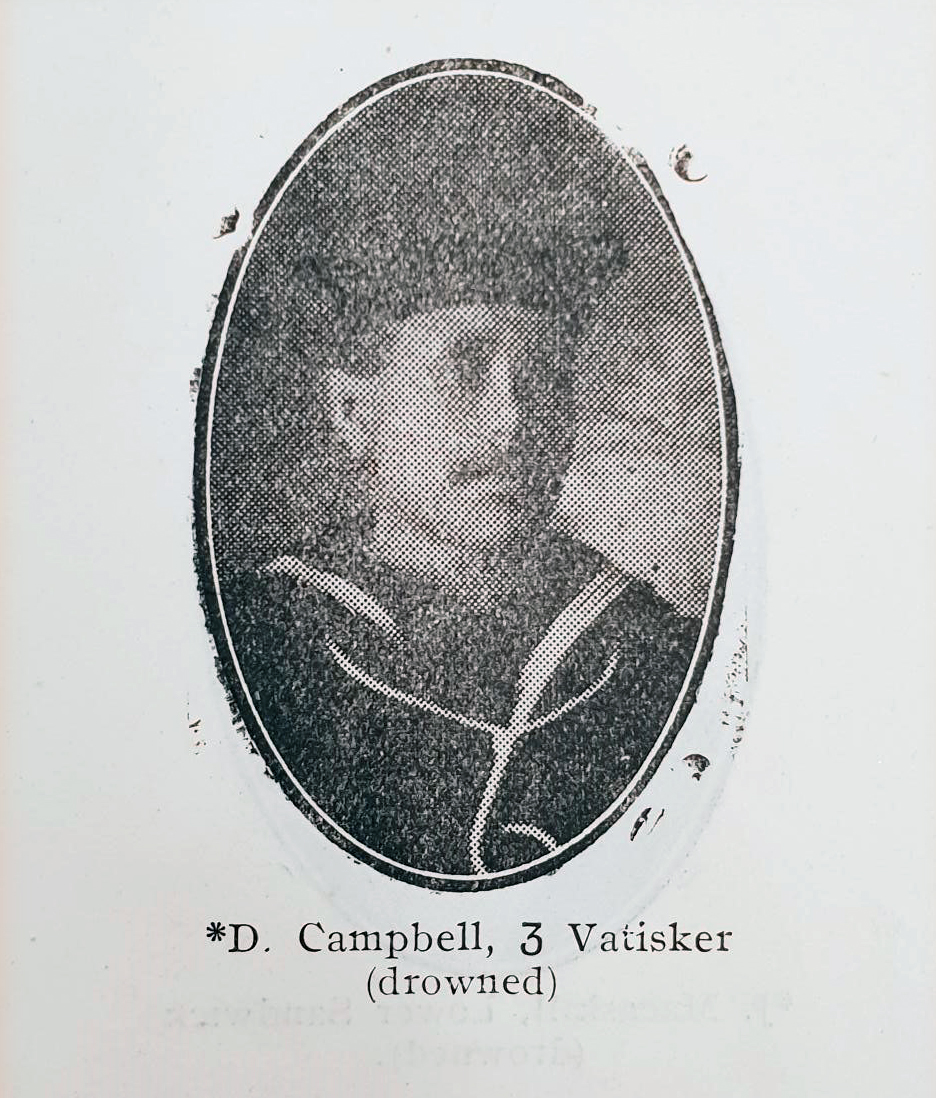

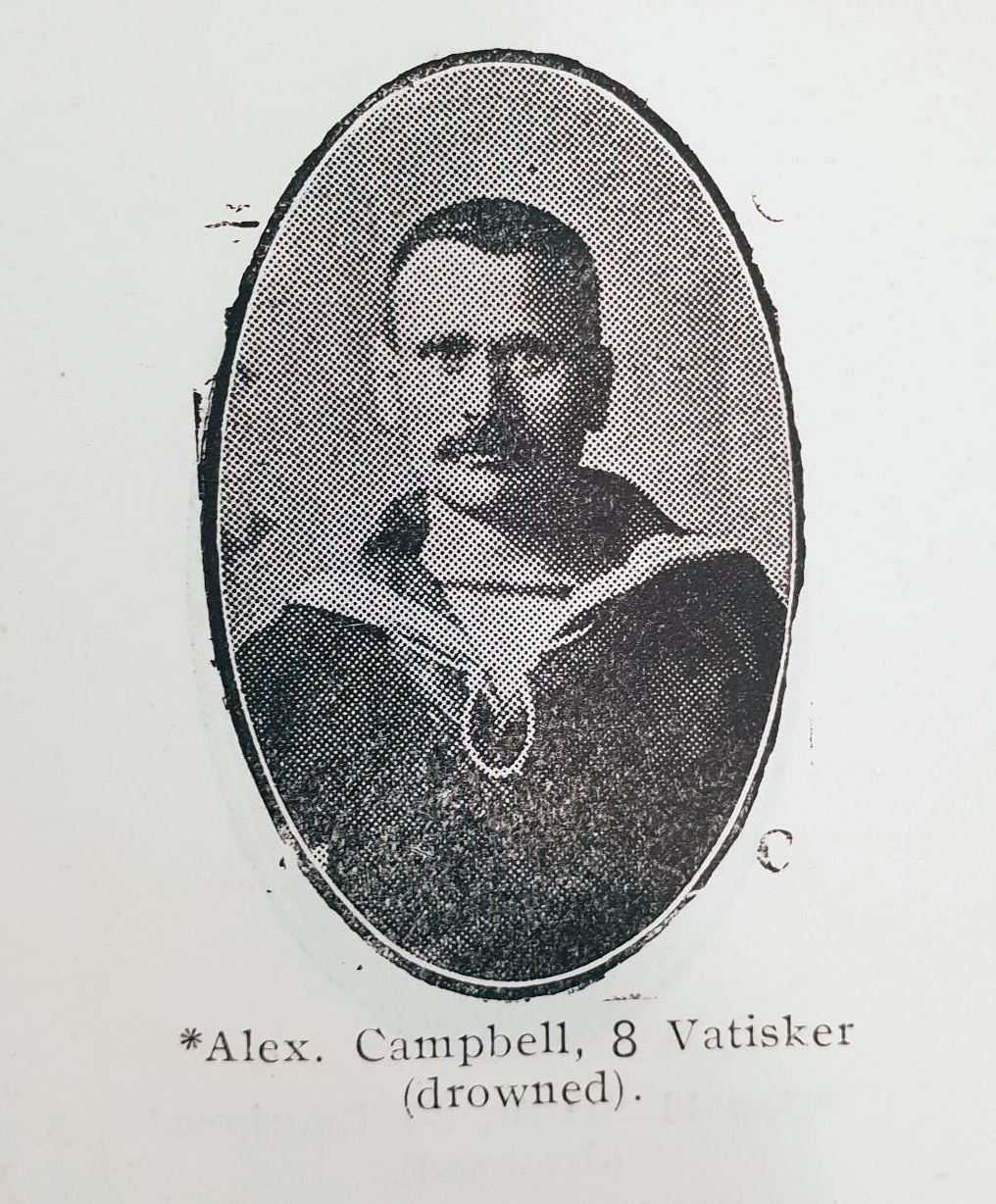

Leading Seaman 2058/C Donald Campbell served in the Royal Naval Reserve (RNR), listed as on the strength of HMS Pembroke, the shore establishment. He was married to Catherine Campbell. Donald Campbell’s testament contains a revealing inventory listing his unpaid wages, the value of his possessions, the ‘war gratuity’ payable to his widow and the RNR gratuity for his service, a total of £133.7s.11d (equivalent to purchasing power of about £5,250 in 2018). His younger brother Alexander Campbell, who lived nearby at 8 Vatisker, also died in the disaster on 1 January 1919, aged 42, but his body was never recovered. He was a Leading Seaman, 2999/C, on HMS ‘Victory’, married to Jessie Graham.

Donald and Angus Campbell of Vatisker, Lewis. 'Loyal Lewis Roll of Honour 1914 and After' (Stornoway, 1920), pp.30-31.

Images used under Creative Commons Attribution International License 4.0

Another of the dead was Angus Macdonald, who lived at 42 Leurbost, Lochs, Lewis, with his wife Mary. A Royal Naval Reservist, no 1830/D, nominally attached to HMS Imperieuse, a receiving ship from which personnel were posted. On his death at the age of 45, his Post Office savings account was found to be worth £402 (equivalent to purchasing power of about £18,600 in 2018).

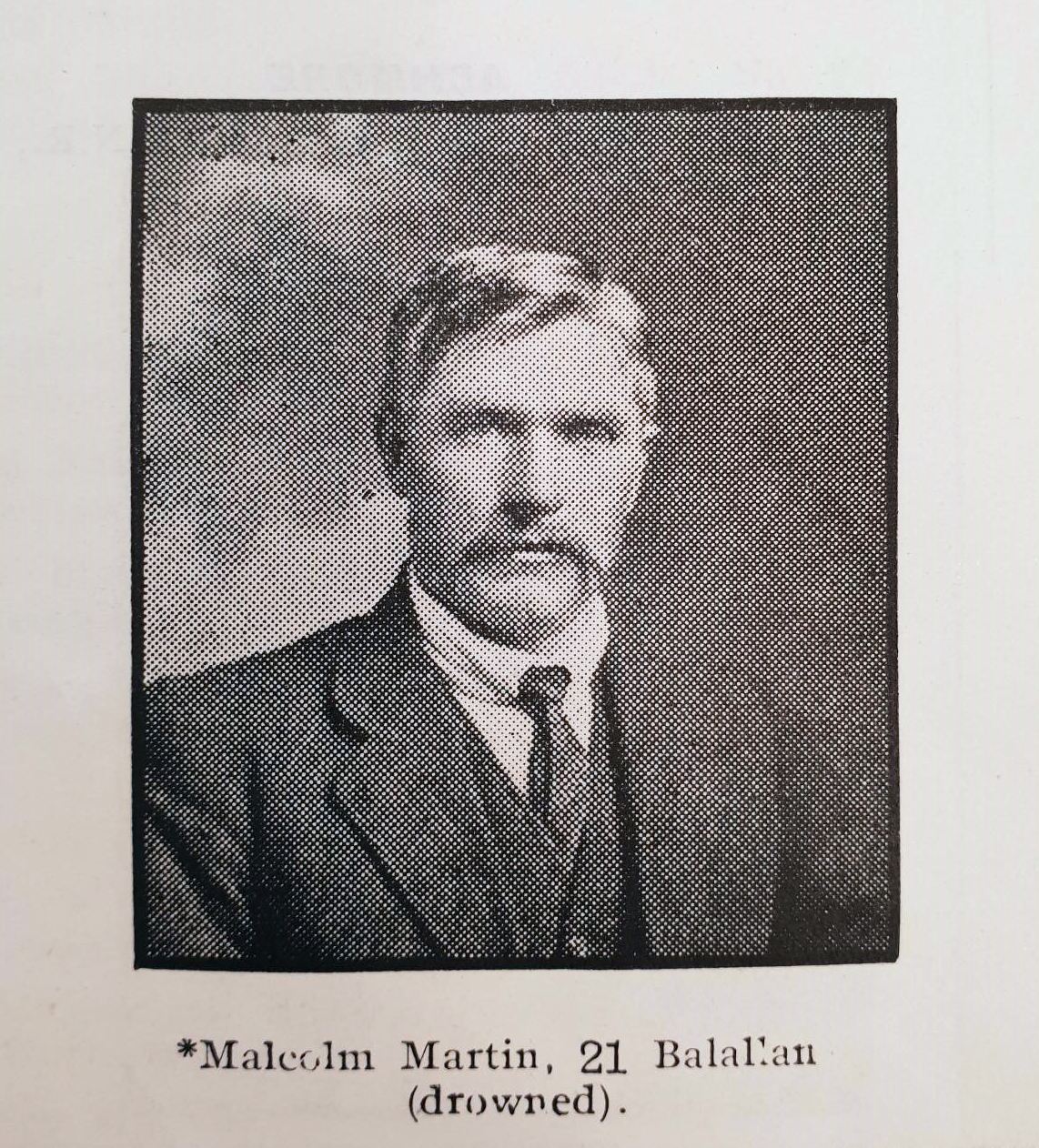

Malcolm Martin, 21 Balallan, Lewis. 'Loyal Lewis Roll of Honour 1914 and After' (Stornoway, 1920), p.322.

Image used under Creative Commons Attribution International License 4.0

In the pre-war years a labourer named Malcolm Martin left Lewis in search of a better life, eventually finding work as a shepherd at Punta Arenas in Southern Chile. Why he left is unclear, but in October 1906 he and another man were fined three guineas at Stornoway Sheriff Court for breach of the peace and malicious mischief. In a dispute possibly connected to elections to the Balallan School Board, they had hurled peats, smashed windows and broken into the schoolhouse, whose occupants they frightened. (British Newspaper Archive, ‘Inverness Courier’, 12 October 1906; petition for bail, 1906, NRS, SC33/37/1906/52)

Martin was back home on a visit when war broke out in 1914. Unable to return to South America, he was living in his parents’ house at 21 Balallan and helping his father Donald’s croft. In 1916, like many other young men in the district, he appealed against conscription. He claimed that he had set himself up in South America with horses and land, and needed to return to look after them. Read about his appeal case in the ScotlandsPeople website.

After the local tribunal rejected his appeal Martin joined the Royal Naval Reserve. He is listed on the strength of HMS Pembroke, the shore establishment at Portsmouth, but like other RNR personnel from Lewis, probably served on auxiliary naval vessels. And like other Lewismen serving in the RNR, he boarded the Iolaire for the voyage home on 31 December 1918. He died in the wreck, and his body was buried at Laxey Cemetery, Lochs. His death is recorded both in the register for Stornoway registration district and the Extracts from Navy Returns of Deaths (Minor Records vol. 146 in ScotlandsPeople).

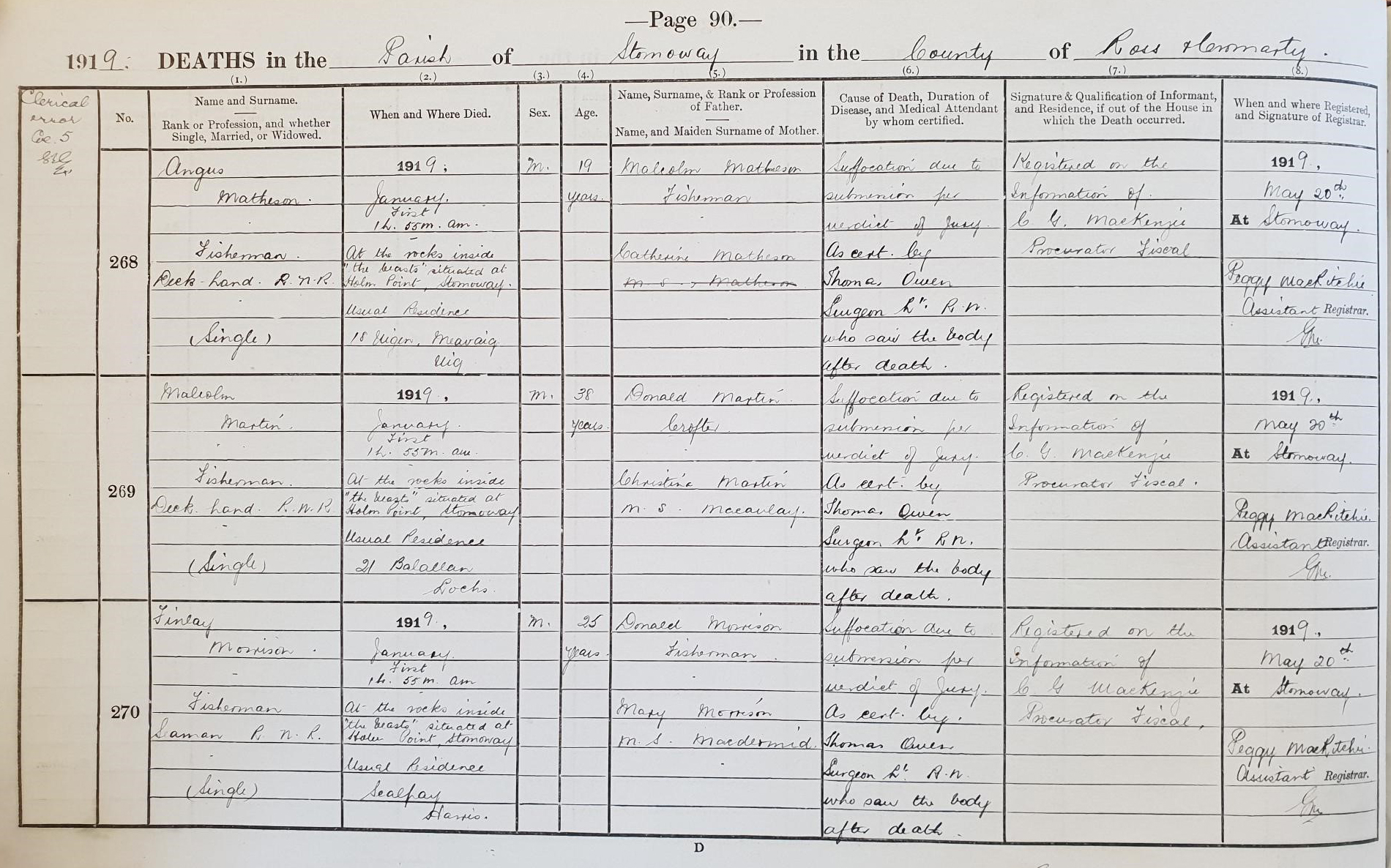

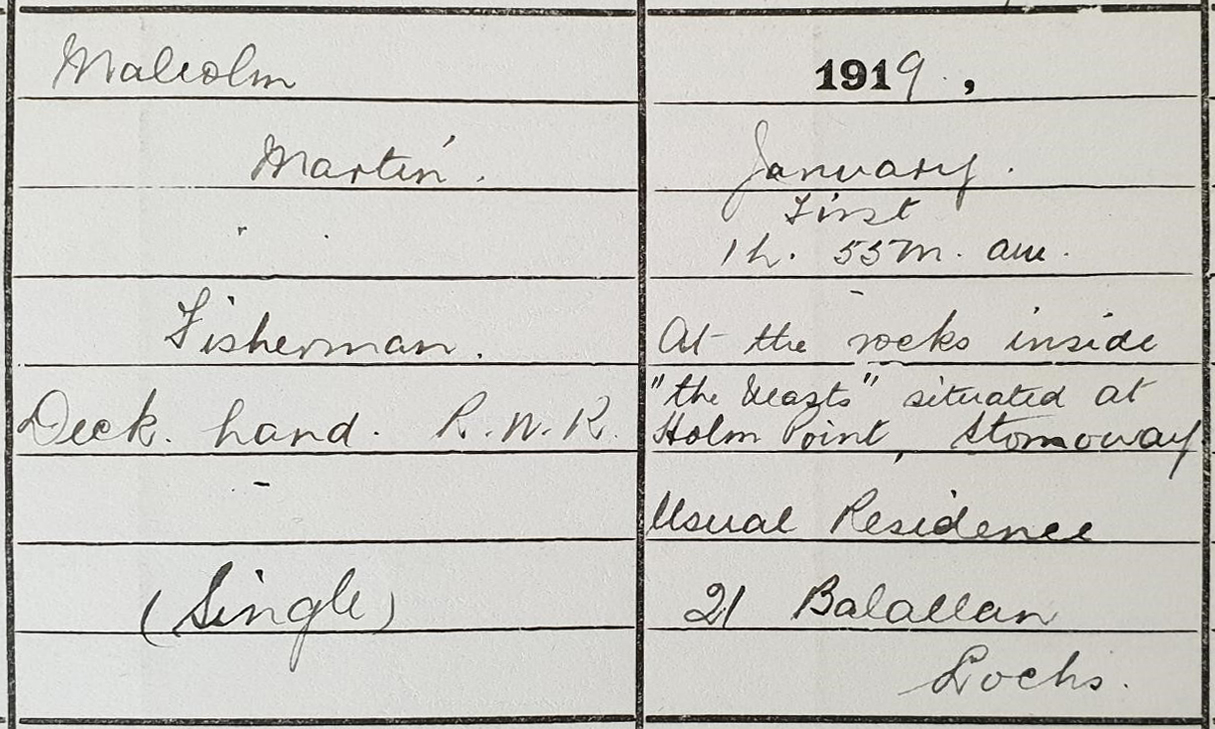

Register of Deaths, and detail of entry for Malcolm Martin, 1 January 1919

National Records of Scotland, Register of Deaths 1919, Stornoway District, 88/269

Credit: Image supplied by the artist. williambwallacecollection.co.uk

This commemorative painting ‘Known Unto God’ by William Wallace, a distant relative of Malcolm Martin who died on the Iolaire, was completed in 2019 to mark the 100th anniversary of the maritime tragedy. The painting depicts multiple objects that the men would have carried including photographs of loved ones, gifts for children for New Year and memories of home such as the Callanish Stones, black house and Lews Castle. Symbolism can be seen in the form of a mournful centaur which represents ‘The Beasts of Holm’ (the rocks which the Iolaire struck on that fateful morning) and a dead eagle; the yacht’s name in Gaelic.

In common with the rest of Scotland, and particularly with people involved in agriculture, a typical reason for Lewis men to object to being conscripted was the hardship that would be caused to their families by their absence on military service. The tribunal might postpone their call-up date to allow them time to arrange for assistance on their croft. Many eligible men living on crofts at Balallan appealed against conscription, and were generally refused.

In 1916 Malcolm MacIver’s appeal came from no. 40 Breasclet, Stornoway. A remarkable letter of support was written by his father Neil and sixteen neighbours at Breasclet on 21 May 1917, highlighting the precariousness of the crofters’ existence. They requested that Macolm be granted condition exemption because of his mother’s age (72) and poor health, the mental incapacity of his sister, ‘who has constantly to be under close supervision’, and the absence in France of his brother. If Malcolm were called away from home ‘the usual annual supply of peats are uncut, and will remain so’, and ‘croft-work, cattle and sheep shall go unattended – in fact home and croft shall soon become vacant' (SC33/62/1/90).

Of Malcolm’s two brothers on active service, John was also in the RNR, but survived the war. Neil MacIver, an NCO in the 2nd Battalion, Seaforth Highlanders, died of gas poisoning on 5 May 1915.

Another islander who was conscripted and subsequently died on active service was Evander Mackenzie (or McKenzie), a mason and crofter of 13 Branahuie, by Stornoway, who joined 2nd Battalion, Seaforth Highlanders, and died in France on 10 May 1917. His conscription appeal papers are in NRS (ref SC33/62/1/37).

Learn more about Military Service Appeals Tribunal records.

Some Lewis men escaped potential death on the Iolaire by the chance of being selected to sail on the vessel 'Sheila', which departed from Kyle of Lochalsh after the Iolaire. Others slipped aboard the 'Sheila' without permission. They included Donald “Dòhmnall Magaidh” MacDonald who had twice avoided being killed during his wartime naval service. As he later recounted:

‘The third time my life was saved, I was on my way home when the Iolaire was lost. The Iolaire came to pick up the sailors. There were that many going home that New Year and the Sheila could not take them all. I was on board the Iolaire when this soldier that I knew shouted to me “Donald, I have got a bottle of Whisky and would be very happy if the two of us were going across together. I wonder if I gave you a soldier’s coat and a hat could you pretend to be a soldier.” I got on the Sheila through mischief and that saved my life that night.’

(Extract of recollection told to Angus Campbell, 'Am Puilean', who was interviewed and recorded by Comunn Eachdraidh Nis (Ness Historical Society), courtesy of the Society)

Donald "Dòhmnall Magaidh" MacDonald. Courtesy of Linda Sinclair

The statutory registers

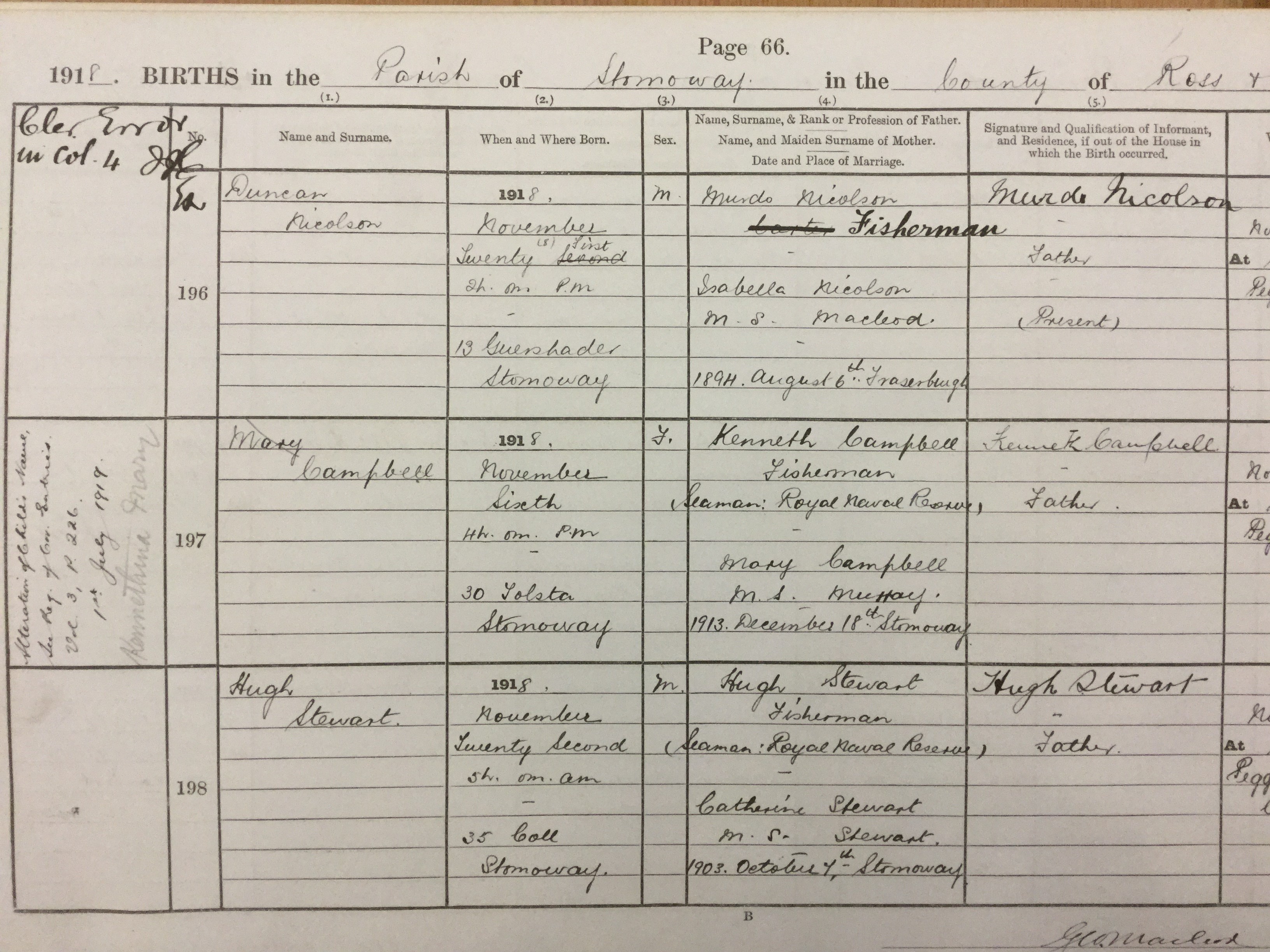

The statutory registers of births, deaths and marriages also help to cast light on the families caught up in the tragedy. For example, the births registered in Stornoway during 1918 include many children born to fathers then serving in the Royal Naval Reserve. Several of them died in the Iolaire disaster, but many survived the war and returned home safely.

Among the children born to fathers on active service was Mary Campbell, born on 6 November 1918. Her father Kenneth Campbell was born in 1889, the son of a crofter, and was a fisherman when he married Mary Murray, a fish worker, on 18 December 1913. During the First World War served as a seaman on HMS Galatea, a light cruiser-turned-minelayer. In 1917 and 1918 he lost two brothers who were killed while serving in the RNR. On 25 November 1918 he was in Stornoway to register his daughter’s birth, and was among those who died in the wreck of the Iolaire. Seven months later his widow registered a change of name for their daughter, who was to be called ‘Kennethina Mary’ in his memory. (Kennethina Mary married John Denoon in 1940, and died in 1999.)

Either side of Mary Campbell in the Register of Births are Duncan Nicolson and Hugh Stewart. Their fathers also earned their living at sea, but their fortunes differed from Kenneth Campbell’s, and reflect the fact that the majority of Lewis men did not die on wartime service. Murdo Nicolson, born in 1866 at Back, Stornoway, followed his father’s calling as a fisherman and survived the war. Hugh Stewart, born in 1878, was another fisherman. He served in the Royal Naval Reserve and lived to see the peace.

Birth entry for Mary Campbell and others, November 1918. National Records of Scotland, Register of Births, Stornoway District, 1918, 88/212

Registering the deaths

The huge loss of life on the Iolaire posed a challenge for the Registrar of Births, Deaths and Marriages for Stornoway District, George Macleod, and his assistant, Peggy MacRitchie.

The status of the servicemen on board, and the fact that the bodies of several men were never found, complicated the task of registering their deaths. Twenty officers and crewmen of the Iolaire perished, but seven survived. Twelve of the deaths were registered soon after the disaster, on 5 January 1919, on information supplied by the Captain of the Naval Depot at Stornoway (Britain’s largest Royal Naval Reserve base). These twelve deaths were registered to help the families of the dead. Almost all of them lived in England. The bodies were despatched from Stornoway on 4 January.

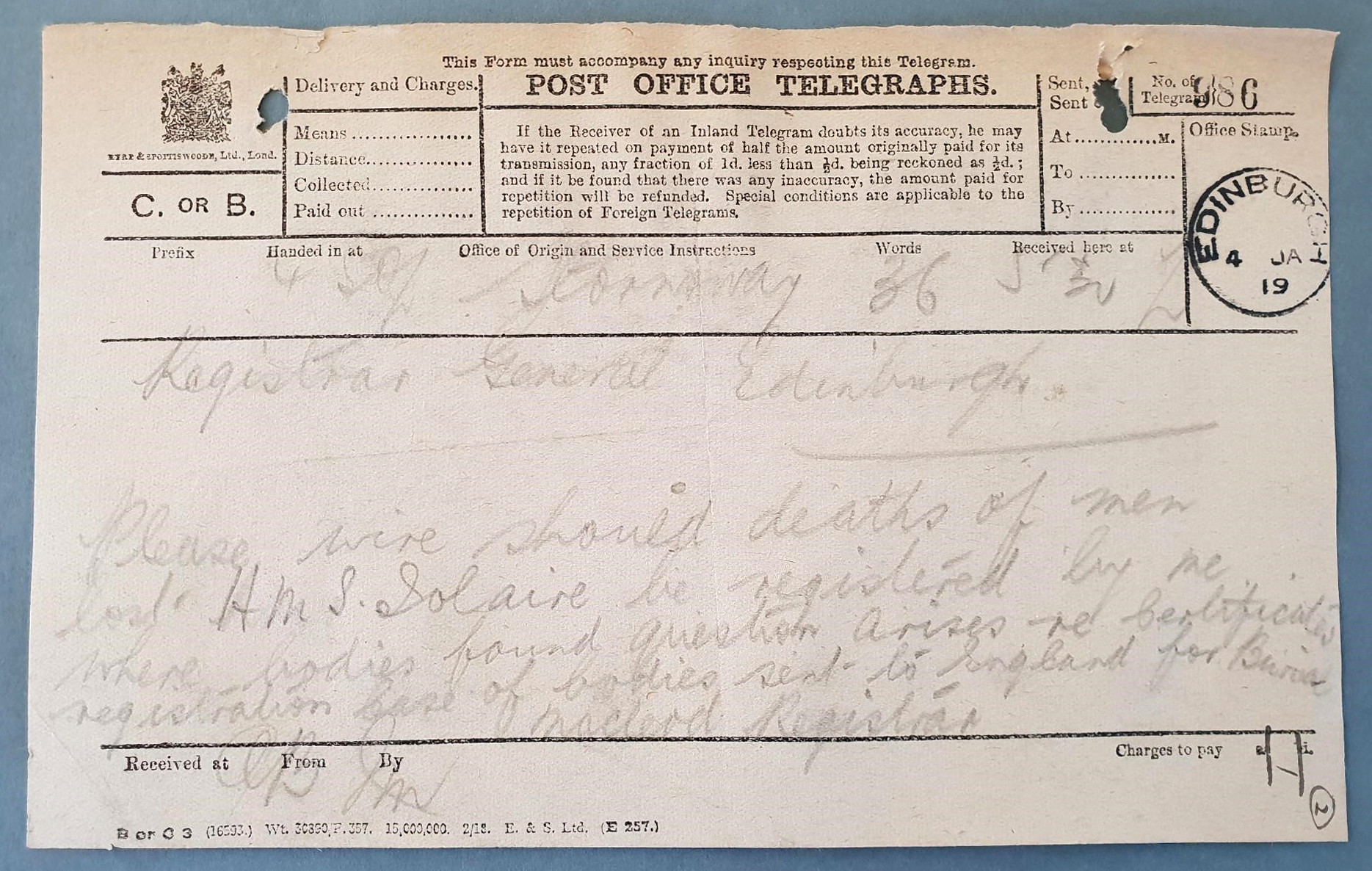

Telegram from the Registrar at Stornoway to the Registrar General, requesting guidance on registering deaths of men whose bodies were being sent to England 4 January 1919. National Records of Scotland, GRO5/1076

On 10 February 1919, concerned that only twelve registered deaths were reported in the monthly returns, the Registrar General asked the Registrar how registration of the deaths was progressing.

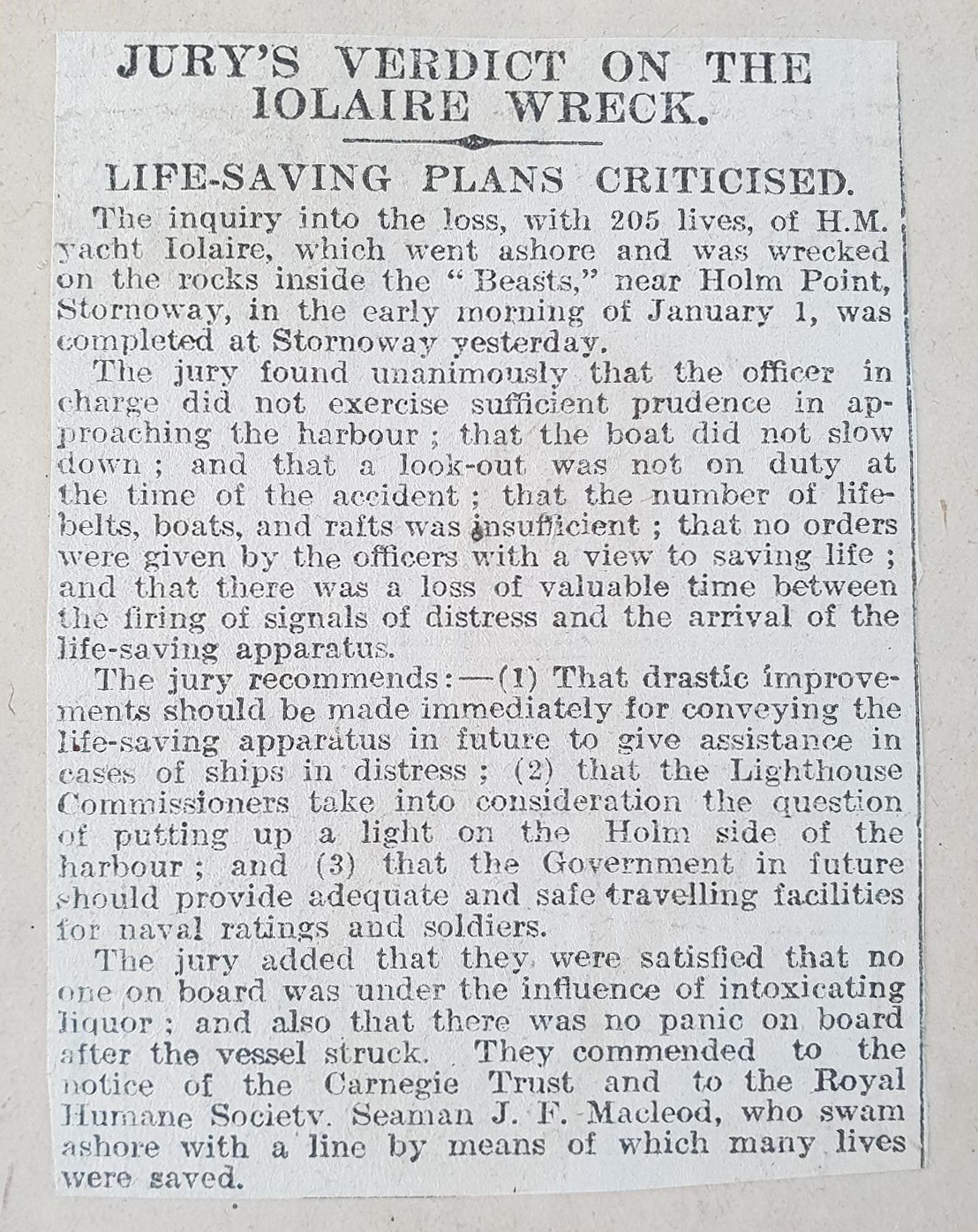

In other marine disasters involving fatalities the Procurator Fiscal examined the available evidence regarding the deaths of British subjects and submitted a Report of Precognition to the relevant Registrar. Soon after the ‘Iolaire’ disaster the Procurator Fiscal in Stornoway indicated to the Registrar that he would not be supplying such reports. He may have been anticipating the need for a Fatal Accident Inquiry (FAI), which was sat on 10 - 11 February 1919. Among its findings were the inadequate response of the boat’s crew to the initial impact, the insufficient number of life- belts, boats and rafts, and the delay in deploying life-saving apparatus on the shore.

Report of the FAI findings. National Records of Scotland, GRO5/1076

Following the verdict of the FAI, the cause of death by ‘drowning’, which had been entered for the twelve deaths registered to date, was corrected on 31 March 1919 to ‘suffocation due to submersion’. This cause of death became the standard for almost all the other ‘Iolaire’ deaths that were registered; from late March until late May 1919 more than 100 of the deaths were registered. They were mostly of seamen like Malcolm Martin and Kenneth Campbell who had served in the Royal Naval Reserve. Some deaths were not registered until after bodies were recovered when the wreck was raised. The deaths of another 80 or so RNR and RNVR men were not registered until the period 29 November - 29 December 1919. Many of these deaths were of men whose bodies had not been recovered. The delay probably added to the anguish of the families involved. The work was stressful for the Registrar, and for his assistant, Peggy MacRitchie, who resigned in 1920 ‘because she felt the work too heavy for her’.

The Iolaire Disaster Fund

In response to the disaster, on 6 January an all-male committee was formed ‘to provide assistance for the dependants of men who lost their lives in the wreck of His Majesty’s yacht ‘Iolaire’ at the entrance of Stornoway Harbour’. The Iolaire Disaster Fund was quickly constituted and opened to public subscription. The first registered donation was £1,000 from Lord Leverhulme, who owned Lewis and Harris. Other donations and fundraising concerts during 1919 gathered a total of £29,116. 7s.

Payments to families who had lost fathers, brothers or sons typically ranged from £7 to £9. 10s per year. In 1919 payments to dependants amounted to £2,198. 11s. 4d.. The fund had supported 201 families by the time the final payments were made in January 1938, when the last children of the dependants turned 18 years old.

Sources/Further Reading

This article draws on various records held in National Records of Scotland.

ScotlandsPeople, Statutory Registers of Births, Deaths and Marriages, and Corrected Entries

National Records of Scotland, File on deaths at sea, 1914-1926 (GRO5/1076)

National Records of Scotland, Examiners’ reports on registers in 1919 (GRO1/65, p.85)

ScotlandsPeople, Military Service Appeal Tribunal cases, Stornoway Sheriff Court records (SC33/62)

National Records of Scotland, Inland Revenue file on Iolaire Disaster Fund (IRS21/1338)

Hebridean Connections, Iolaire Disaster Fund: volumes and papers

John Macleod, ‘When I heard the bell: the Loss of the Iolaire’ (Birlinn, 2009)

Naval-History.net, An Index to "British Warships 1914-1919" by F. J. Dittmar & J. J. Colledge

National Records of Scotland, Open Book, The Sinking of the Tuscania, 1918

‘Loyal Lewis Roll of Honour 1914 and After’ (Stornoway, 1920)

‘Dol Fodha na Grèine: The Going Down of the Sun: The Great War and a Rural Lewis Community’ (Stornoway, 2014)

‘The Darkest Dawn: The story of the Iolaire Disaster’, Malcolm Macdonald and Donald John MacLeod (Stornoway, 2018)