The Battle of the Somme - More Stories

The Battle of the Somme - More Stories

This feature tells the stories of Scottish soldiers and units on the Somme front in France from early July until mid-November 1916. Separate features, Battle of the Somme 1916 on this website and Stories of the Somme on the ScotlandsPeople website, highlight stories of eight men who took part in the initial assaults on 1 July.

Private Thomas Murray, 9th Battalion, Cameronians, 6 July 1916

Second phase of battle - life and death in the front line

Private Alexander Dryburgh, 2/7th Battalion Royal Warwickshire Regiment, 19 July 1916

1/6th Battalion, Black Watch, 25-30 July 1916

Private Andrew McNulty, 16th Battalion, Royal Scots, 1-3 August 1916

Private Robert Purves, 5/6th Battalion, Cameronians (Scottish Rifles), 29 August 1916

Lt the Hon Edward Wyndham Tennant, 4th Battalion, Grenadier Guards, 22 September 1916

Private William Broad Grossart, 1/9th Battalion, Highland Light Infantry,

1 November 1916

Private John Wood, 1/5th Battalion, Gordon Highlanders, 13 November 1916

Private Thomas Murray, 9th Battalion, Cameronians (Scottish Rifles)

6 July 1916

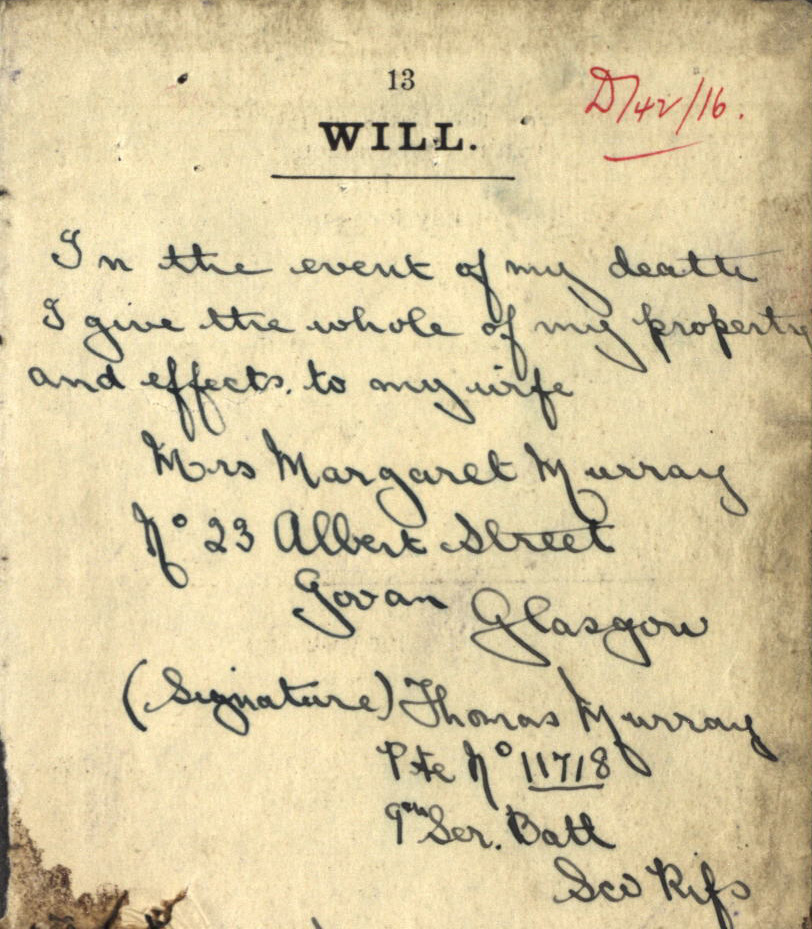

Few documents reflect so starkly the carnage of the prolonged Battle of the Somme than the will of Thomas Murray, 11718 Private, 9th Battalion, Cameronians (Scottish Rifles), who was killed in action on 6 July 1916.

Detail of Thomas Murray’s will (286 KB jpeg)

National Records of Scotland, SC70/8/370/78/3

During the first day of the Battle of the Somme the 9th Cameronians remained in reserve as part of 27th Brigade, 9th Division, and on 3 July moved up to the front line at Montauban. When the Cameronians relieved the 2nd Battalion, Wiltshire Regiment, heavy German shelling depleted their initial strength of 20 officers and 659 men. The work of consolidating their front line trenches was made difficult by heavy rain and very dangerous by artillery fire. The Battalion’s war diary in The National Archives records that between 3 and 8 July, when the Cameronians were relieved, their casualties amounted to 32 dead, 5 died of wounds, 100 wounded, and 2 missing believed killed.

One of the 11 men killed on 6 July, when the enemy artillery was ‘most active’, was Private Thomas Murray, aged 24. His will from his pay book is preserved in NRS, with those of six of his comrades who also died that day. Like other soldiers, Murray probably carried his pay book in a breast pocket of his tunic. The document is the usual simple will, but it testifies to the terrible effects of shellfire in the blood-stained impact marks of the piece of shrapnel that probably contributed to Murray’s death.

Although his will was recovered, his body was subsequently lost, and he is commemorated on the Thiepval war memorial to the 72,000 men with no known grave on the Somme. A full image of Thomas Murray’s will (352 KB jpeg) can be seen here.

Thomas Murray was born in Govan, Glasgow, where he enlisted with hundreds of other volunteers in the locally-recruited battalion of the Cameronians. Before the war he seems to have followed his father into one of the Govan shipyards, where he worked as a plater’s boy. In 1913 he married Margaret McDonald, to whom he left everything in his will, written on 13 May 1915, the day after his battalion landed in France. The will is unusual because a comrade with a practised hand may have written and signed it on his behalf. The couple's first son had died in infancy, and the second, John, was born shortly after Thomas went to France. It seems the family were reunited during a brief leave from the Front that Thomas enjoyed in about January 1916, for Margaret gave birth to a daughter, Jane, on 15 September 1916.

Second phase of battle – life and death in the front line

Assaults along the British front were renewed on 14 July on a much reduced scale and at fewer points. The high ground around Bazentin and Longueval was a target with the aim of straightening the new front line in preparation for a later campaign.

Once again the attacking divisions suffered heavily. The 51st Highland Division took 3,500 casualties for few gains, although the 9th Division fared better in winning ground on Longueval Ridge. Nearby the 8th Brigade (in 3rd Division) attacked north of Montauban, where for example the 1st Battalion, Royal Scots Fusiliers, was held up by uncut barbed wire, one of the factors that had made 1 July a disaster. Sixty men were killed by enemy fire on the slopes of the Longueval Ridge. This was the local cost of the British strategy of attrition. Incrementally such losses amounted to 9,000 British casualties on 14 July, and many more over the following weeks.

Private Alexander Dryburgh, 2/7th Battalion Royal Warwickshire Regiment,

19 July 1916

On 19 and 20 July further attacks began on the Somme sector. In order to exploit any weaknesses in the German defences caused by the transfer of troops to reinforce the Somme, the British pressed home attacks elsewhere. At Fauquissart near Aubers Ridge, about 50 miles north of the Somme, 182nd Brigade took up a position on the front line, having embarked for France on 22 May. The brigade mainly consisted of battalions of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment.

Serving in D Company, 2/7th Battalion was Alexander Dryburgh (born 1892), on attachment from the Highland Cyclist Battalion, an example of the many Scots who served in English regiments. On 29 May 1916 he wrote to his father John Dryburgh, a coalminer, and his stepmother Ann, who lived in Coaltown of Wemyss, Fife. He enclosed a copy of the will in his pay book, and joked about his comfortable brick bed, and the shelling by the ‘Grey fellows’ that rocked him in his sleep. To avoid the censor’s pen he described his location as the ‘land Watt’s in’, referring to his cousin Walter Dryburgh of the Machine Gun Corps.

As part of what became known as the Battle of Fromelles, at 6pm on 19 July the battalion attacked the Germans’ well-prepared positions. The Warwickshires made some gains before being forced to withdraw two hours later, having suffered casualties of 13 officers and 305 NCOs and men. Alexander Dryburgh was one of the many killed. The day after he wrote his letter, another cousin, John Dryburgh, a sergeant in the 8/10th Gordon Highlanders, died elsewhere on the Western Front. John’s younger brother Watt, who won the French Medaille Militaire, lost his life a year later on 1 August 1917.

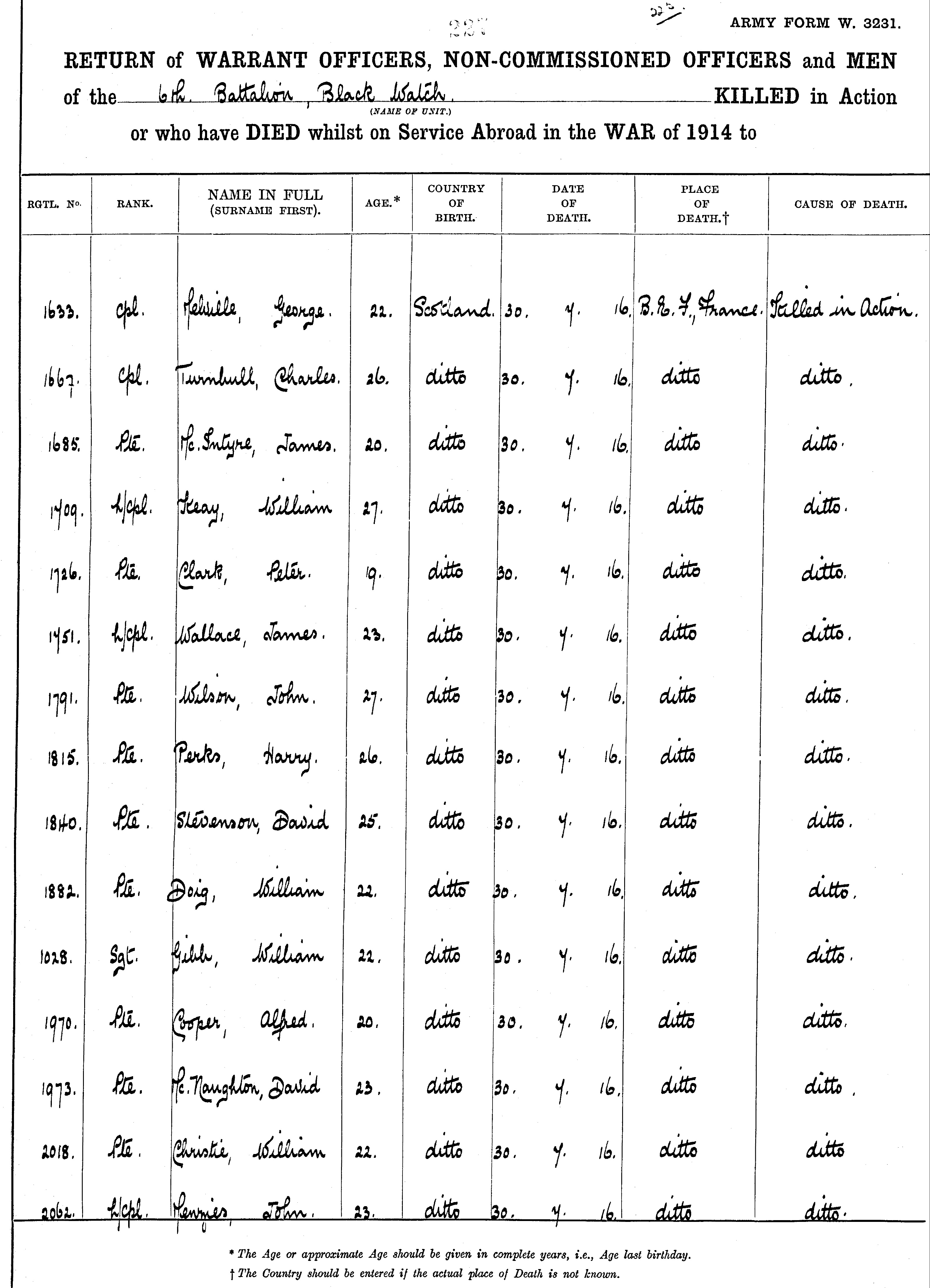

1/6th Battalion, Black Watch, 153rd Brigade, 51st (Highland) Division

25–30 July 1916

On 25 July, in preparation for a divisional attack as part of the protracted battle for Bazentin Ridge, the battalion moved up from a reserve position at Mametz to the front near Bazentin-le-Grand. It lost men killed and wounded by shellfire in the days before it was ordered to make its first attack on 30 July. Supported by other battalions and the 29th Division, the 1/6th Black Watch assaulted High Wood, south west of Bazentin-le-Grand and Bazentin-le-Petit, and was met by heavy machine gun fire. The attack failed. More than 100 officers and men were killed after the 1/6th moved into the front line. The deaths in this Territorial battalion fell heavily on its Perthshire recruiting grounds, for example in the parish of Tibbermore near Perth, which lost four men that day.

Deaths of members of 1/6th Battalion, Black Watch, 30 July 2016

National Records of Scotland, Minor Records, volume 123/225

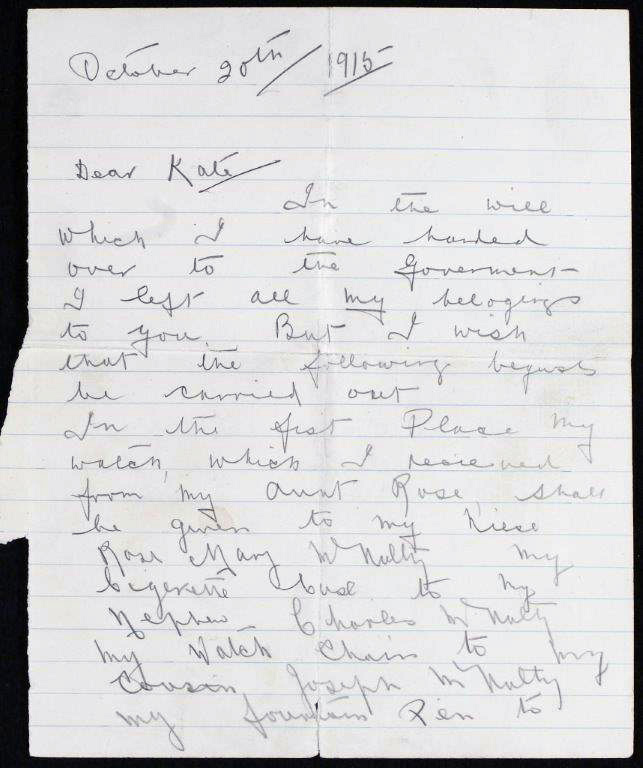

Private Andrew McNulty, 16th Battalion, Royal Scots, 101st Brigade, 34th Division

1-3 August 1916

Having suffered very heavy losses on 1 July, the 16th Battalion, Royal Scots were once again in action. On 31 July they moved up into the line at Bazentin-le-Petit. During the following days, when the battalion raided the Germans in their newly-created trench called the ‘Intermediate’, many men were killed by heavy shellfire. During the night of 3-4 August, two companies took part in what was planned to be a wider assault in the area, and their costly failure to capture ‘Intermediate’ led to unjust criticism by the divisional commander of a battalion still weak after 1July.

Among the casualties in the first three days of August was Private Andrew McNulty, a grocer and member of the Independent Labour Party in peacetime. Owing to battlefield conditions his body was not found and he is commemorated on the Thiepval memorial. He was born in 1887 in Cockpen, Midlothian, four months after his father Charles, a paper mill worker, died of tuberculosis. For years he lived with his uncle Jeremiah McNulty at Mauricewood farm, Glencorse, and latterly worked for the Penicuik Co-Operative Association. On the outbreak of war he enlisted in the 16th Battalion, Royal Scots, also known as McCrae’s after its gallant commanding officer and founder, Sir George McCrae.

In October 1915 while the battalion was at Sutton Veny near Warminster, Andrew contemplated his possible death during the inevitable overseas posting. His thoughts turned in gratitude and love to his extended family, and he wrote to his aunt Kate, asking ‘all my friends to think of me at my best, to remember the good of me and forget the bad.’ Kate was to be his main beneficiary, and his brother, cousins, nieces and nephews were to receive choice possessions. The McNultys were Roman Catholics, and Andrew wished a mass to be said annually for the repose of the soul of Kate’s older sister, his beloved aunt Rose (1855-1911), ‘who was more than a mother to me’. (NRS, SC70/8/415/77, letter from Andrew McNulty to his aunt, Kate McNulty, 20 October 1915)

First page of letter from Andrew McNulty to Kate McNulty (131 KB jpeg)

National Records of Scotland, Soldiers’ Wills, SC70/8/415/77

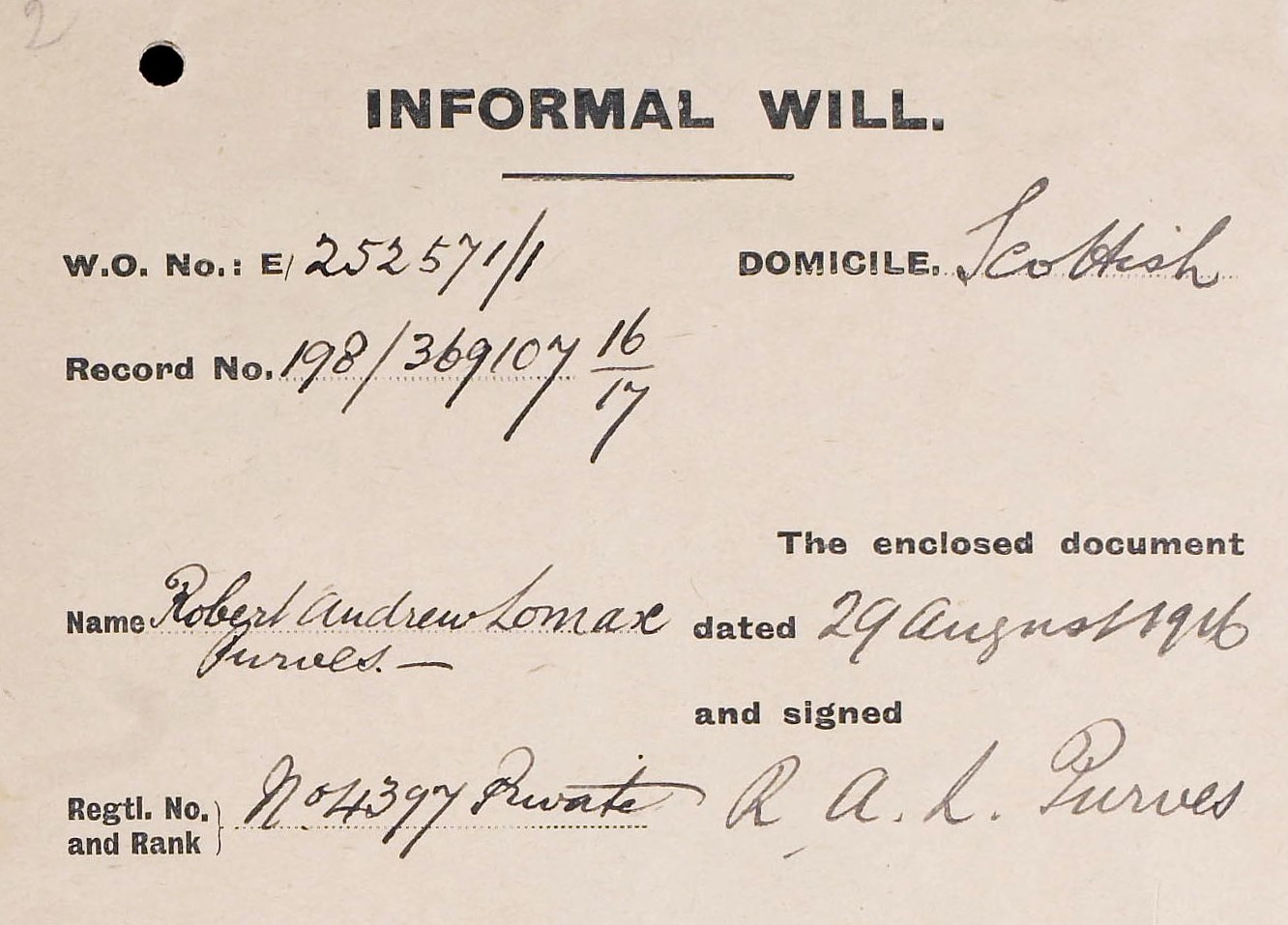

Private Robert Purves, attached to 5/6th Battalion, Cameronians (Scottish Rifles), 19th Brigade, 33rd Division

29 August 1916

Detail of envelope of Purves's will, 1916 (197 KB jpeg)

National Records of Scotland, SC70/8/418/2/1

Occupying front-line trenches that were subject to enemy artillery bombardment, sniping and raids told on the nerves of officers and men alike, and could drain men’s physical as well as mental resilience. It was not uncommon for soldiers to inflict wounds on themselves in order to be removed from the front line, but it was rare for men to kill themselves.

In late August, a private in the 5/6th Battalion of the Cameronians (Scottish Rifles), despaired of ever getting home to see his parents near Prestonpans in East Lothian, and decided that he could not ‘stand the hardships and sufferings of this life any longer’. On 29th August 1916 he shot himself through the head with his rifle, and died soon afterwards. A note that he wrote in his pay book made his feelings and intentions explicit. It was the main evidence that led the Army’s Court of Enquiry held the following day to conclude that he intended to kill himself. The original document is preserved among the Soldiers’ Wills in NRS (SC70/8/418/2), while his service record, containing the Court’s findings and related papers, is in The National Archives (WO363/P1669, ff.182-256).

According to his service record Robert Andrew Lomax Purves was a twenty-nine year old law clerk when he signed up for military service at the recruiting office in Edinburgh on 3 December 1915. He was single, slightly-built and short-sighted. At the end of January 1916 he joined the 9th Battalion, Royal Scots at Glencorse Barracks. After only a few months’ training, on 14 July he was sent to France, and on 22 July was attached to 5/6th Battalion of the Cameronians (Scottish Rifles), a recent amalgamation of the 1/5th and 1/6th Territorial battalions. In August his unit was in reserve at Fricourt Wood in the middle of the Somme sector, in preparation for a renewed assault in October.

On 1 August Purves wrote a will making his mother beneficiary of his ‘property and effects’ – he was an only child. On 29 August, when he had resolved on his final course of action, Purves hoped that God would ‘bless and comfort’ his parents, and that Mr Clarkson and Mr Collins, ‘two fine officers’, would survive. His pals were to have any of his personal possessions at the front, something that was usual after a soldier died. The stark words of his note are the only known evidence of his thoughts and feelings as he contemplated without hope his future in the war. In handling his will the War Office recorded the cause of his death as ‘Killed in Action (self-inflicted)’, but in the Service Returns of Deaths and elsewhere it became simply ‘killed in action’.

- Images of Robert Purves's will and note 1916 (900 KB pdf)

- Transcript of Robert Purves's will and note 1916 (65 KB pdf)

The battles of September 1916

From early September a series of heavy British attacks gained ground, driving the Germans from their second and third lines. The strongpoints of Guillemont, Ginchy, Delville Wood and High Wood were taken, which opened the way for further advances. During the Battle of Flers-Courcelette, which began on 15 September, the British deployed tanks for the first time in warfare. Canadian and New Zealand divisions also fought for the first time and distinguished themselves. Among the many British units involved was the Guards Division, which as soon as it concluded its part in the costly fighting at Flers-Courcelette, was preparing for a renewed offensive on 25 September, which became known as the Battle of Morval. Even holding the confused front line between attacks was very dangerous.

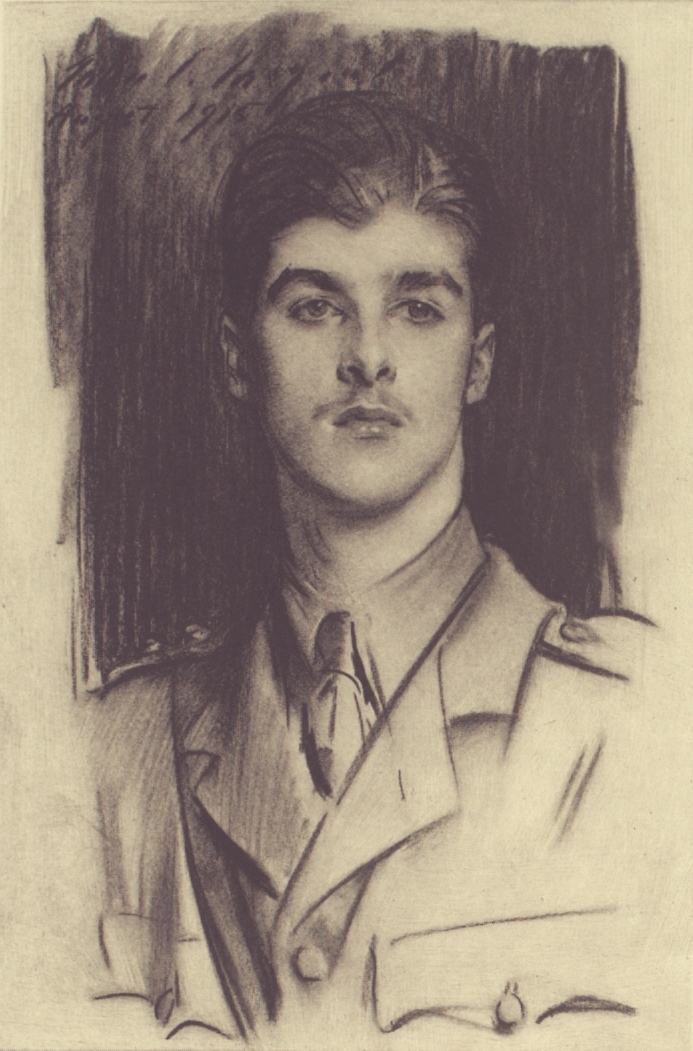

Lieutenant the Honourable Edward Wyndham Tennant, 4th Battalion, Grenadier Guards, 3rd Guards Brigade

22 September 1916

Portrait of E W Tennant by John Singer Sargent, 1915 (296 KB jpeg)

National Records of Scotland, GD433/2/357/83, p.8 courtesy of Michael Brander

In late September 1916 the 4th Battalion of the Grenadier Guards, part of the 3rd Guards Brigade, was in the line near the newly-captured village of Guillemont. One company occupied an exposed position in a sap, or projecting trench, whose other half was occupied by German troops. Among the company’s officers was Lieutenant Edward Tennant. On the night of 21-22 September, while attempting to snipe the Germans, Tennant was himself shot in the head by a sniper, a fate that befell many soldiers at the front who were picked off in unlucky or careless moments. His death at the age of nineteen was mourned by the men whom he commanded as well as by his fellow officers.

The Honourable Edward Wyndham Tennant was born in 1897, the son of Sir Edward Tennant, whose family originated in Glasgow and great great grandson of Charles Tennant, the founder of an industrial chemical empire based in Glasgow. Married to the aristocratic Pamela Wyndham, Sir Edward pursued a political career as a Liberal MP, and in 1911 was raised to the peerage as 1st Baron Glenconner. At the age of five Edward attended the village school near The Glen, the family’s baronial mansion near Peebles. Later he was privately educated and became in some ways a typical product of the class and education system that supplied the British Army with most of its junior officers during the Great War. Of the 594 boys who left his boarding school, Winchester, in the six years before the war, 531 joined up before conscription started in 1916. Having left school in 1914 with the intention of visiting Germany to learn the language in preparation for a diplomatic career, Tennant volunteered in August 1914. As a former member of the school’s officer training corps, he was quickly commissioned as a subaltern, despite being under age at only seventeen years old.

Known to family and friends as ‘Bim’, Edward Tennant was born to a privileged position, but he belonged to an even smaller elite. His mother was one of ‘the Souls’, the social and intellectual circle of the 1880s and 1890s which included A J Balfour, the Conservative MP, and members of the Asquith family. Edward’s aunt Margot Tennant was married to Herbert Henry Asquith MP, so he went to war as the Prime Minister’s nephew. With his family firmly embedded in the Anglo-Scottish establishment, it was natural for him to join the senior guards regiment. In August 1915, at the end of a year’s training, Tennant’s likeness was capture by the fashionable artist John Singer Sargent. Soon afterwards the eighteen year-old subaltern was posted to the Western Front with his battalion, in time to see action in the Battle of Loos in late September.

Like others of his generation and class, Tennant was schooled in the values of faith, patriotism, duty, courage, and sacrifice. By all accounts he more than fulfilled the expectations placed on him as a leader, and although severely tested by front-line conditions, he was full of fun and took pains not to show fear to his men. As one of them wrote: ‘When things were at their worst, he would pass up and down the trench, cheering the men’ (‘Edward Wyndham Tennant: a Memoir’, p. 242). His help and encouragement, and no doubt the extra cigarettes that he obtained for his soldiers, reportedly endeared him to them. To the battalion he was known as the ‘Boy Wonder’, and his fine character was also appreciated by his brother officers, who included Harold Macmillan, a future prime minister.

Tennant had another quality that distinguished him from most of his comrades. From his schooldays he was a budding poet, and his first published volume, ‘Worple Flit’, appeared in the month he was killed. In October 1916 a memorial service was held in St Margaret’s, Westminster, timed to allow MPs and peers to attend. To family and friends attending the service, his grieving mother distributed a private commemoration, a copy of which is preserved among the Balfour family papers (National Records of Scotland, GD433/2/357/83). It reproduced Sargent’s portrait, which reappeared in his mother’s memoir in 1919.

Excerpts from printed commemoration of E W Tennant

National Records of Scotland, GD433/2/357/83 (625 KB pdf)

Tennant’s cousin Raymond Asquith, son of the premier, a barrister and fellow Grenadier officer, was killed as the Guards advanced in the battle of Flers-Courcelette on 15 September. They were buried in the same cemetery row. Another cousin, Mark Tennant of the Scots Guards, was killed on 16 September. The loss of these and other members of the youthful generation of Britain’s cultural and political elite has helped shape posterity’s perception of the Great War. The question of what they might have achieved had they survived is unanswerable, as it is for countless other humbler combatants.

Final phase November 1916

By the end of October successive British attacks had gained the high ground along the centre and right of the Somme front, and were pushing against German defences further back, despite being hampered by torrential rain and appallingly muddy conditions. Positioned on the far right of the British units where they adjoined the French forces, the 100th Brigade in 33rd Division included the 1/9th ‘Glasgow Highlanders’, a territorial battalion of the Highland Light Infantry.

Private William Broad Grossart, 1/9th Battalion, Highland Light Infantry, 100th Brigade, 33rd Division

1 November 1916

Private William Grossart of 9th Battalion had turned twenty on 12 July 1916. Born in Alloa in 1896 to an unmarried servant, Betsy Scott, William was adopted at a young age by Betsy’s sister Helen and her husband John Grossart, a bakery manager. Later the family moved to Glasgow, where John worked as a shoemaker. William enlisted in Glasgow and was posted to France by 1916.

Like other British soldiers, Grossart had the remarkably efficient army postal service to thank for the delivery of mail and parcels sent from home - the lifeline that connected soldiers to their family and friends. Parcels of treats such as cake, tinned food, sweets and chocolate supplemented the monotonous army rations, and were usually shared with comrades. The touching birthday letter that Grossart received is proof of a mother’s love, and survives because he wrote his will on it, leaving everything to her.

On 1 November 1916, 100th Brigade was part of a co-ordinated assault with the adjacent French forces on German positions east of Lesboeufs. Attacking in late afternoon, the Glasgow Highlanders and the 2nd Battalion Worcestershire Regiment struggled forward over very muddy and cratered ground, into which they sank, only to come under devastating machine gun fire. About 100 Glasgow Highlanders and 80 Worcesters died in the failed attack. So bad were the conditions that the remains of very few men were identified for burial, and most, including William Grossart, were therefore commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial. Many more were wounded, some of them surviving in the open until 3 November, when a second attack by two other battalions allowed them to be rescued. But the 1/9th also had to cope with the loss of their inspirational commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel J C Stormonth-Darling, who was killed by a German sniper on the morning of 1 November.

- Images of letter to William Grossart (1.1MB pdf)

- Transcript of letter to William Grossart (62KB pdf)

Private John Wood, 1/5th Battalion, Gordon Highlanders, 153rd Brigade, 51st Division

13 November 1916

On 13 November, among the many Scottish units fighting in the final assault of the Battle of the Somme, known as the Battle of the Ancre, was 51st Highland Division, tasked with the capture of part of the German lines at Beaumont Hamel. It included the 1/5th and 1/7th territorial battalions of the Gordon Highlanders.

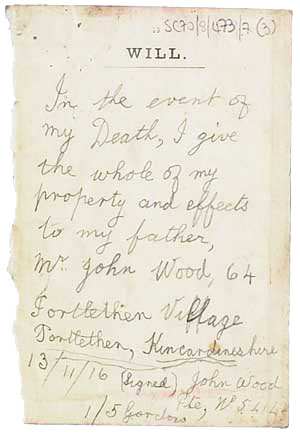

On the morning of 13 November 1916, before going over the top to attack the German positions, an eighteen year old British soldier wrote his will in his pay book. Private John Wood was born into a fishing family, in Portlethen, Kincardineshire, but at the outbreak of war it was the army that he joined, along with many other men of this coastal community. Wood and about 60 other ranks of the 1/5th Battalion were lost that day, alongside 6 officers. Some 9,500 Gordon Highlanders died during the First World War, and the wills of almost 3,000 of them are held in NRS.

John Wood’s will, 13 November 1916 (41 KB jpeg)

National Records of Scotland, SC70/8/473/7/3

The 51st Highland Division captured its objectives on 13 November, and its success cemented its reputation as a fine fighting force. The capture of Beaumont Hamel was achieved at the cost of 2,200 casualties, far fewer than the loss of more than 5,000 men of the 29th Division during its failed attack on the same German strongpoint on 1 July 1916. Nevertheless, British casualties were so high, and the weather so adverse, that further attacks on the Somme were cancelled. The British Army had suffered about 400,000 killed, wounded and missing since 1 July. Counting the French and German casualties, the total has been estimated at more than one million men.

Further sources:

- Wills of Scottish soldiers, NRS, searchable in ScotlandsPeople

- National Records of Scotland, Private Papers, Balfour papers, GD433

- Battalion War Diaries, The National Archives, Kew

- Imperial War Museum website feature: Lt Robert Stewart Smylie, Royal Scots Fusiliers, killed 14 July 1916

- Trevor Royle, ‘Flowers of the Forest: Scotland and the First World War’ (2006)

- Jack Alexander, 'McCrae's Battalion' (2003)

- Alexandra Churchill, ‘Somme: 141 days, 141 lives’ (2016)

- ‘Edward Wyndham Tennant: a memoir by his mother Pamela Glenconner with portraits in photogravure’ (1919)

- John Lewis-Stempel, ‘Six Weeks: The Short and Gallant Life of the British Officer in the First World War’ (2010)

- Alec Weir, ‘Come on Highlanders: Glasgow Territorials in the Great War’ (2005)

- Commonwealth War Graves Commission website

- Scottish National War Memorial website

- The Long, Long Trail website