The Munitionettes and the work of women in the First World War

The Munitionettes and the work of women in the First World War

The Munitionettes, or Canary Girls as they were known, were part of the female work force that took up war-time employment in the production of munitions during the First World War as both the demand for munitions at the war front increased and the male work force was depleted.

Nitric acid retorts and receivers in operation (12 July 1918), National Records of Scotland, GD1/1011/61

After the outbreak of the war the shortage of munitions became increasingly acute. While attempts were made to increase production by encouraging overtime among the existing male workforce and through the recruitment of older men, factories were still unable to meet the Government’s desperate need for munitions. Although the Government recognised that it would need to encourage and utilise the remaining female workforce at home there was great reluctance to introduce women into this type of work, with trade unions concerned about how this would affect the working rights of the men upon their return from war, the hostility of existing male workers to women encroaching on their job opportunities and the general uncertainty as to whether or not women would be capable of such work.

![Women workers testing condenser tubes at John Brown & Co's yard at Clydebank. Hostility to women 'dilutees' is evidence in the chalked message, 'When the boys come [back] we are not going to keep you any longer girls', National Records of Scotland (archive reference: UCS1/118/Gen/393/10)](/files//research/image.jpg)

Women workers testing condenser tubes at John Brown & Co's yard at Clydebank. Hostility to women 'dilutees' is evidence in the chalked message, 'When the boys come [back] we are not going to keep you any longer girls', Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland, UCS1/118/Gen/393/10

This attitude and concern was shared not only by those in the Munitions trade, but more broadly by the workers and employers in trades regarded as ‘men’s-work’. Despite these reservations, reports were conducted early on as to the suitability of women to meet the demands of such work. As early as 1915 the Ministry of Munitions Supply Committee made recommendations on the employment and remuneration of women on munitions work. This helped contribute to agreed suitable conditions by which a woman could be employed, and the War Office published several guides as to the employment of women.

Women's War Work

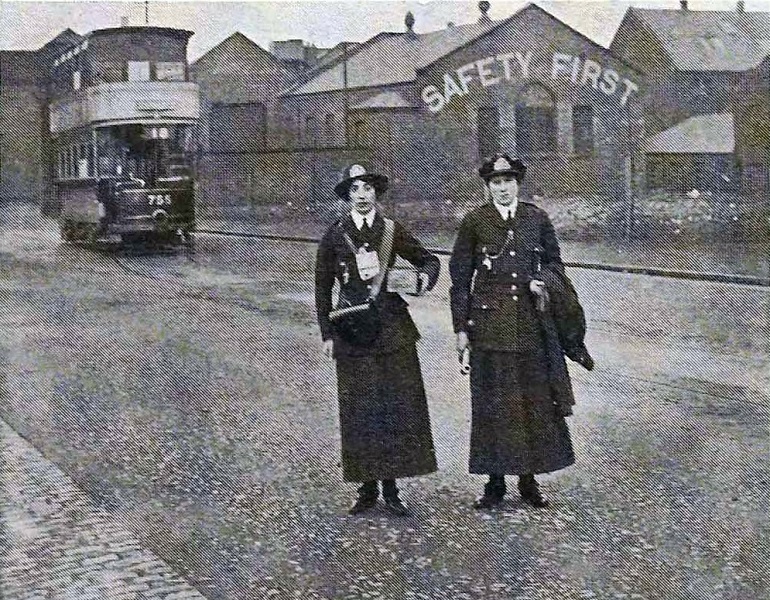

In the National Records of Scotland one such publication is Women’s War Work (archive reference: HH31/27/2) issued by the War Office in September 1916 which explains the need for women in employment and provides a detailed list of processes ‘In which women are successfully employed’. To complement this the War Office also included several photographs of women situated in trade occupations, presumably as visual proof of the women’s abilities.

National Records of Scotland, Top to Bottom: HH31/27/49, HH31/27/3 and HH31/27/3

All of this work helped to contribute to the implementation of a system of ‘dilution’. This was an agreement made between management and trade unions that assisted in replacing skilled workers with unskilled or semi-skilled workers including older men, women and the disabled. The unions accepted this proposal on three main conditions; firstly that laws would be put in place to stop people making profits out of the war; that the measures would only last for the duration of the war; and thirdly that women would get paid the same wages as the men. This measure was put in place to maintain the rate at which male workers were paid, rather than out of solidarity with the suffragette movement or recognition of equal pay, as demonstrated by the evidence submitted by the National Union of Clerks in 1916:

“EQUAL PAY. There can be no possible doubt that to safeguard the interests of men enlisting that the same rate of pay must be paid to the women undertaking their duties. But it may be found that work previously done by two men is now divided amongst three women. In this case the aggregate salaries must not be less than the total amount paid to the two men. This ensures that the Employer get financial inducement to replace the male clerk by a lower paid female". (14th December 1916, HH31/27/17)

Despite the initial reluctance of employers and the trade unions to employ women, once these agreements were in place the Government set about advertising and encouraging both employers and women to join industrial life.

The Aberdeen Daily Journal, 7 March 1916

“The appeal just issued by the Committee appointed by the Board of Trade and the Home Office or more women to take the places of men in industrial occupations, enforces once again the immense value which women have been to the trade of the country during the present war. With the intuitive gift of genius, Mrs Pankhurst, at the very outset of the war recognised that a new era in the importance of women in this country was about to dawn and without hesitation she took her stand on the side of King and country”. (Press cuttings, HH31/27/57)

The Times, 6 March 1916

“Meanwhile the Home Secretary and the President of the Board of Trade have addressed an appeal to all employers in the manufacturing industries calling attention to the urgent necessity of concerted action to make good the loss of labour caused by withdrawal of men for the Forces…The situation demands prompt and vigorous action. Men are rapidly being withdrawn…The one source of supply is the great body of women at present unoccupied or engaged only in work not of an essential character.” (Women for Men’s Work: Ministers’ Appeal to Employers, HH31/27/3)

This process of ‘dilution’ became an extremely effective way of dealing with the nation’s shortage of manpower.

National Records of Scotland, HH31/27/3

While the promise of equal pay to women was never fully realised and many employers found ways to underpay their female staff, the contribution of these women stopped industrial and commercial life from grinding to a halt and acted as ‘good press’ for the country’s war effort. The war also offered a previously impossible opportunity of greater freedom and travel from home for women and raised the voice of the suffrage movement in gaining the right to vote, even if the first realisation of this right in the Representation of the People Act 1918 limited the ability to vote to women aged over 30.

Despite the success of women in these roles, the raised profile of women’s suffrage and the implied possibility of continued entrance into the workforce, concerns about women in the workplace and how this would impact working men when they returned, remained.

The Aberdeen Daily Journal, 7 March 1916

"One may deplore the entrance of women into the industrial market on physical grounds, but as the state has now recognised the woman worker as an essential part of our industrial machine, the end of the war will not see the end of the woman mechanic… The after war problems will by no means concern men only”. (Press cuttings, HH31/27/57)

In reality the employment of women in men’s roles was a temporary wartime measure and by 1924 the Ministry of Labour reported that the ‘reversal of the process of substitution which was so striking a feature of wartime industry is now practically complete’ ('The Flowers of the Forest: Scotland and the First World War' by Trevor Royle, p209).

Many of the records relating to the Government’s research into Women’s Work and the subsequent responses from local authorities, trade unions and public bodies are now available in the National Records of Scotland. In particular the First World War Files (NRS, HH31) contain a wealth of information relating to the First World War including munitions, recruiting and substitutionary labour, food production and more. To look through these records please take a look at the National Records of Scotland's online catalogue.

Resources Used

- Trevor Royle, ' The Flowers of the Forest: Scotland and the First World War'

- Gareth Griffiths, 'Women’s Factory Work in World War I'

- Imperial War Museums, 'A Day in the Life of a Munitions Worker', http://www.iwm.org.uk/history/a-day-in-the-life-of-a-munitions-worker

- National Records of Scotland, First World War Files (HH31)