The Kaiser's Spy in Scotland - Naval Espionage before the Great War

The Kaiser's Spy in Scotland - Naval Espionage before the Great War

In 2014 a secret agent’s spy kit went on display for the first time at National Records of Scotland in an exhibition about German espionage in Scotland before the First World War. The story concerns Dr Armgaard Karl Graves, who undertook a secret mission to Scotland in 1912 under orders from Berlin to obtain vital information about the Royal Navy’s latest weaponry and strength. Graves' covert activities are revealed through his code books, secret messages and intercepted letters. The documents and items seized from Graves, now part of the National Records of Scotland archive collection, also demonstrate how MO5, the forerunner of MI5, carried out its surveillance and capture of foreign agents.

In 2014 a secret agent’s spy kit went on display for the first time at National Records of Scotland in an exhibition about German espionage in Scotland before the First World War. The story concerns Dr Armgaard Karl Graves, who undertook a secret mission to Scotland in 1912 under orders from Berlin to obtain vital information about the Royal Navy’s latest weaponry and strength. Graves' covert activities are revealed through his code books, secret messages and intercepted letters. The documents and items seized from Graves, now part of the National Records of Scotland archive collection, also demonstrate how MO5, the forerunner of MI5, carried out its surveillance and capture of foreign agents.

Anglo-German Rivalry

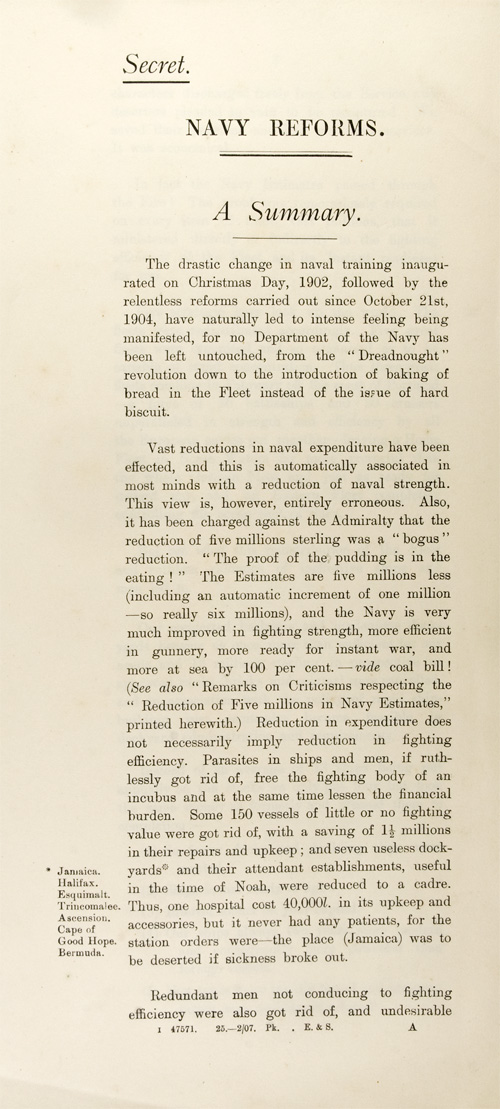

During the 1900s the rivalry intensified between Britain, a long-established global power, and Germany with its growing imperial ambitions. Germany began to build better and bigger ships to develop the capacity to damage the maritime trade of Britain and her allies, France and Russia. From 1898 onwards German efforts to create a more powerful navy prompted the British government to build more warships for the Royal Navy, the prime defender of Britain and her Empire. The policy of maintaining the Royal Navy as a larger force than the next two largest navies combined was no longer affordable. Nevertheless Britain remained committed to a dramatic increase in her naval power. Admiral 'Jackie' Fisher, the First Sea Lord, vigorously led reforms in naval manning and administration, and the deployment of ships.

Printed secret paper entitled 'Navy Reforms'

by Admiral Fisher sent to AJ Balfour, 1907,

National Records of Scotland, GD433/2/45

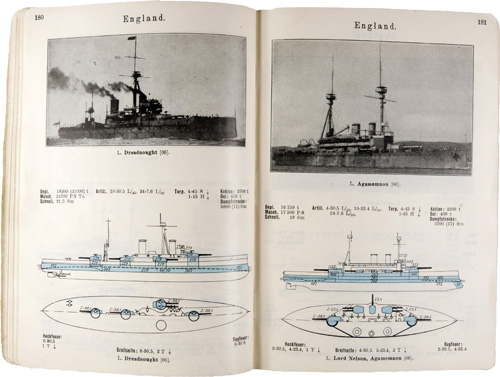

The Navy was made more efficient and far more capable with improved battleships and a new warship, the battlecruiser. The new warships were propelled faster by steam turbines, and they carried uniform guns of larger calibre. HMS Dreadnought was the first of these revolutionary warships and her launch in 1906 forced the pace of the Anglo-German naval arms race.

The battlecruiser New Zealand on the Clyde, 1912,

National Records of Scotland, UCS1/118/Gen/251/1

A German pocket guide to warships shows HMS Dreadnought's superior speed and firepower (ten 12 inch guns) over HMS Agamemnon, armed with guns of various calibres, but only four of 12 inch calibre.

Taschenbuch der Kriegsflotten (1912), pages 180-181,

National Records of Scotland, AD15/12/44B/30

New German warships followed the Dreadnought pattern of more uniform and larger calibres of gun. By 1914 Britain had 29 Dreadnought-type warships and Germany had 17.

Arming the Royal Navy

The Admiralty placed contracts for new warships in England and with several Clyde shipyards, including John Brown & Co. at Clydebank, Fairfield at Govan, and Beardmore's at Dalmuir. This enabled construction of enough battleships, battlecruisers and smaller warships to the latest designs to meet government's production targets. One of the new battlecruisers completed by John Brown & Co. in 1908 was HMS Inflexible, which saw action at the Falkland Islands and Gallipoli.

Launch of destroyer HMS Acasta, John Brown & Co, Clydebank, 1912,

National Records of Scotland, UCS1/118/412/1

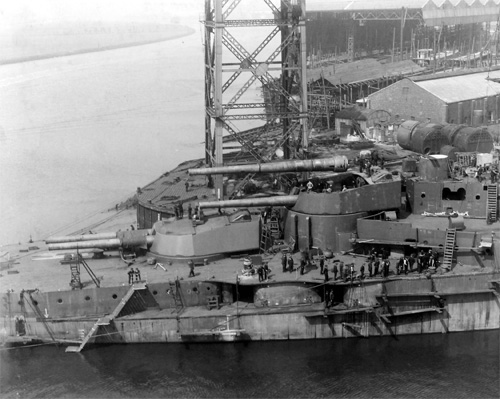

Naval guns were being developed and made by several manufacturers. Beardmore & Co at their Parkhead Works in Glasgow were making the largest guns yet: fearsome 13.5 inch calibre weapons to give devastating firepower to the Navy's latest capital ships. Even larger 15 inch guns were to follow.

15 inch guns being fitted to the battlecruiser HMS Barham

at John Brown & Co, Clydebank, 1915,

Upper Clyde Shipbuilders Collection, Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland, UCS1/118/16/28

German Naval Intelligence & British Counter-Espionage

International rivalry and the naval arms race engendered mutual suspicion between Germany and Britain. Germany's policies gave rise to fear of hostile intentions, particularly of invasion and of spies sent to prepare for it. Newspaper articles and popular fiction not only reflected these twin fears but also fed them. 'The Riddle of the Sands' by Erskine Childers (1903) was hugely popular. One of the stories in 'Spies of the Kaiser' by William Le Queux (1909) features German agents obtaining secret details of the dockyard at Rosyth, a real installation on which work had only just started.

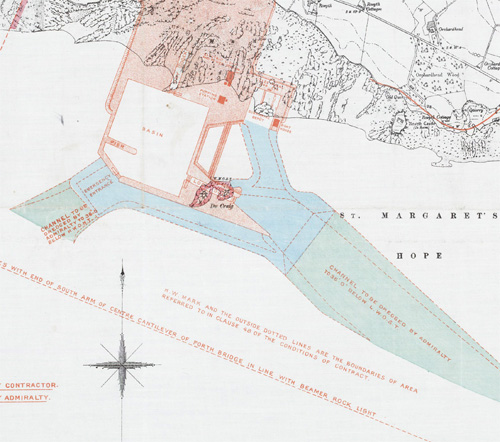

Plan of dredging preparations for the new Rosyth naval dockyard, 1910,

National Records of Scotland, RHP14500/13/1250/1 (detail)

Although German naval intelligence started with few secret agents, the British authorities mostly shared the popular belief in the existence of a network of German spies. This helped the creation in 1909 of the British Secret Service Bureau. Counter-espionage fell to MO5, the War Office's military intelligence section, headed by Captain Vernon Kell. MO5, the forerunner of MI5, used its powers to intercept suspects' correspondence and uncover the activities of German agents and their intermediaries in Britain.

Armgaard Karl Graves, Secret Agent

In 1911 a crisis in relations with Britain prompted German naval intelligence to activate its strategy of using local agents in Britain. They were to observe the movement of Royal Navy vessels and to gather information at naval bases in England and Scotland. As part of the expansion of its spy network, the German spymasters recruited and trained A K Graves. Like some other German agents, Graves had a criminal past. Born in Germany in 1882, he claimed he had spent years abroad in German service. In January 1912, having been trained in codes, explosives and warship recognition, he was sent to Scotland under the flimsy cover of attending medical lectures in Edinburgh.

In 1911 a crisis in relations with Britain prompted German naval intelligence to activate its strategy of using local agents in Britain. They were to observe the movement of Royal Navy vessels and to gather information at naval bases in England and Scotland. As part of the expansion of its spy network, the German spymasters recruited and trained A K Graves. Like some other German agents, Graves had a criminal past. Born in Germany in 1882, he claimed he had spent years abroad in German service. In January 1912, having been trained in codes, explosives and warship recognition, he was sent to Scotland under the flimsy cover of attending medical lectures in Edinburgh.

He arrived in Edinburgh in January 1912 on a mission to observe fleet manoevres, and to report developments in armament and equipment, mainly at the new Rosyth naval base on the Forth, and also in the Cromarty Firth. Information about individual warships was available in specialist publications, including Graves' copy of the 1912 edition of this German handbook of the world's navies. Although bare details of the power, speed and armament of British warships were published, the capabilities of newer vessels were increasingly kept secret.

'Taschenbuch der Kriegsflotten' (1912) found

in Graves' possession at his arrest,

National Records of Scotland, AD15/12/44B/30

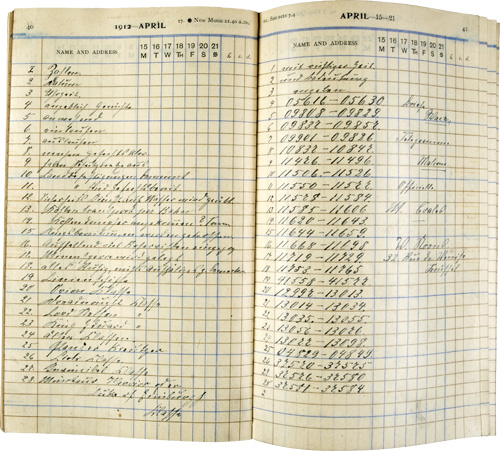

Graves carried codes for sending his messages about British warships, fortifications, naval bases and supply depots. They were written onto sealed pages of a medical diary, a plausible possession for a so-called doctor.

Wellcome's Medical Diary (1912) containing

secret codes for describing naval vessels,

National Records of Scotland, AD15/12/44B/1

While in Edinburgh Graves was given an extra mission to learn about the newest guns being made by Beardmore & Co at their Parkhead works in Glasgow. He noted some technical details of an order for a new 13.5 inch guns, of greater range and destructive power than 12 inch guns, intended for British battleships or battlecruisers.

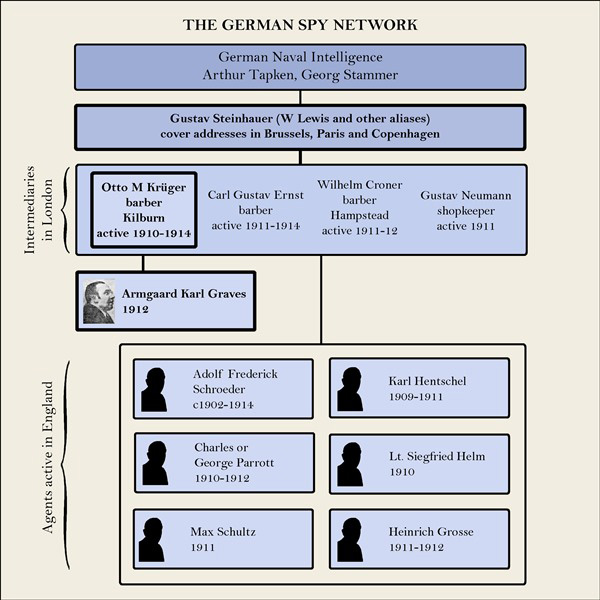

Graves and the German intelligence system

The German spy network in Britain before 1914 was not as extensive as British intelligence believed. Seven agents were spying in the years 1910-1912 - few did so effectively and all were caught. The spymaster Gustav Steinhauer communicated with his agents through Germans resident in London acting as intermediaries. They handled letters and telegrams and forwarded them in either direction. Steinhauer received his mail under aliases in various European cities as he moved about.

Diagram based on Thomas Boghardt, 'Spies of the Kaiser' (2004)

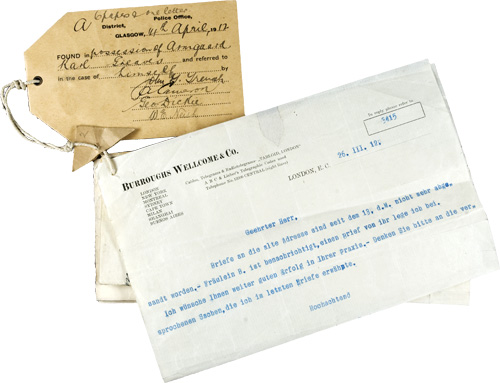

A K Graves sent coded messages to Steinhauer alias 'W Lewis', and received letters addressed to 'James Stafford'. The Post Office returned one letter wrongly addressed to 'A Stafford' to the apparent sender, the medical firm Burroughs Wellcome and Company in London. Suspicious of the cryptic German message and money that the letter contained, as well as the misuse of its stationery, the company handed it to the police.

Burroughs Wellcome & Co, headed letter, 1912,

found in Graves' possession,

National Records of Scotland, AD15/12/44B/19

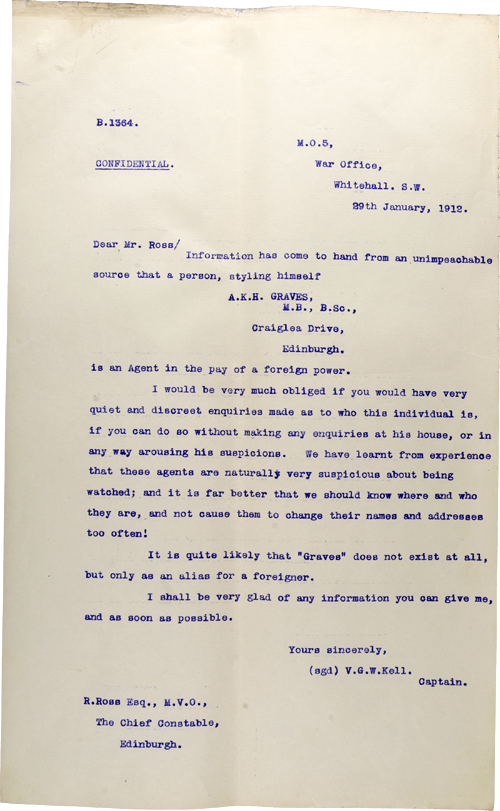

British intelligence was already well aware of Graves because since 1910 they had been intercepting mail passing through the hands of the London intermediaries. Two days after Graves reached Edinburgh, the head of counter-espionage, Vernon Kell, alerted the Chief Constable of Edinburgh, Roderick Ross, to the presence of 'a foreign agent', and requested 'a discreet surveillance'.

Copy letter from Captain Kell to

Chief Constable Ross, 29 January 1912,

National Records of Scotland, AD15/12/44A

At first this worked, but while Graves was on a trip to London, his Morningside landlady told the police of her suspicions about his unusual behaviour. They searched his room, which made Graves realise that he was being watched. On 22 February 1912 Graves tried to bluff Chief Constable Ross into backing off by challenging him to state whether or not the police suspected him of espionage. A week later Graves moved on to Glasgow to gather information about Beardmore's. Fearing that Graves was about to escape, on 14 April 1912 the police dramatically arrested him in the Central Hotel and seized his possessions.

The Evidence

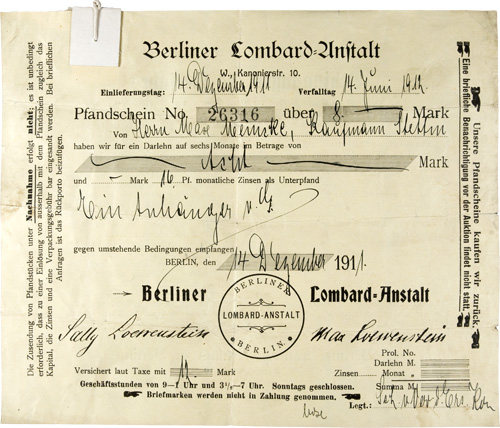

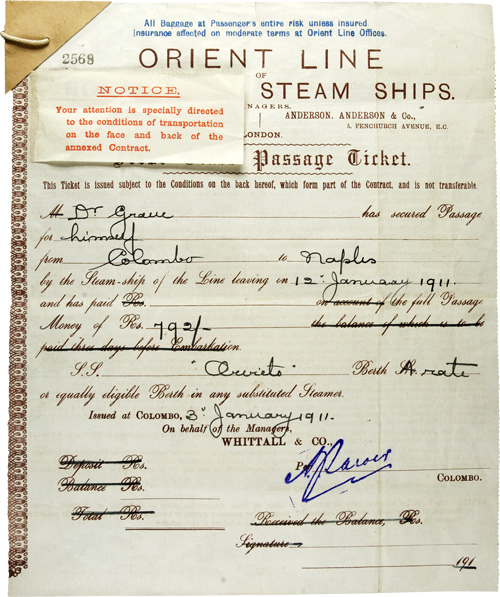

Amongst Graves' personal effects, seized at his arrest, were the code book, maps, photographs and information about Rosyth dockyard. He was also found to be in possession of syringes, drugs and chemicals - for 'experimenting', he claimed, though the prison doctor's report implies that Graves had been taking drugs. He had also purchased shotgun and rifle cartridges in Glasgow - pretending they were for duck shooting, despite it being out of season. Some of his other possessions give clues about his past. In January 1911 he had sailed from Colombo, Ceylon, to Naples under the name 'Dr Graves' and there were postcards to a Martha Brueder and a pawn ticket for a pendant, bearing the name Max Meincke - possibly Graves' real name.

Pawn ticket in Graves' possession,

National Records of Scotland, AD15/12/44B/31

First class passenger ticket on the Orient Line

for Graves' passage from Colombo to Naples, 1911,

National Records of Scotland, AD15/12/44B/21

All these items were tagged by the police for admission as evidence during the trial.

The Trial

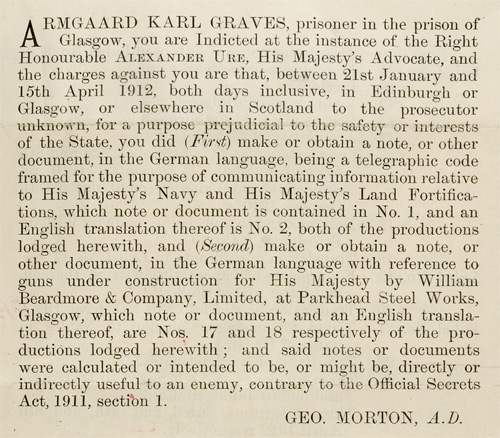

In July 1912 Graves became the first person to be tried in Scotland for offences under the Official Secrets Act, 1911; specifically for communicating information about the navy and land bases, and about guns being constructed at Beardmore's Works.

Indictment against A K Graves, 1912

National Records of Scotland, AD15/12/44A

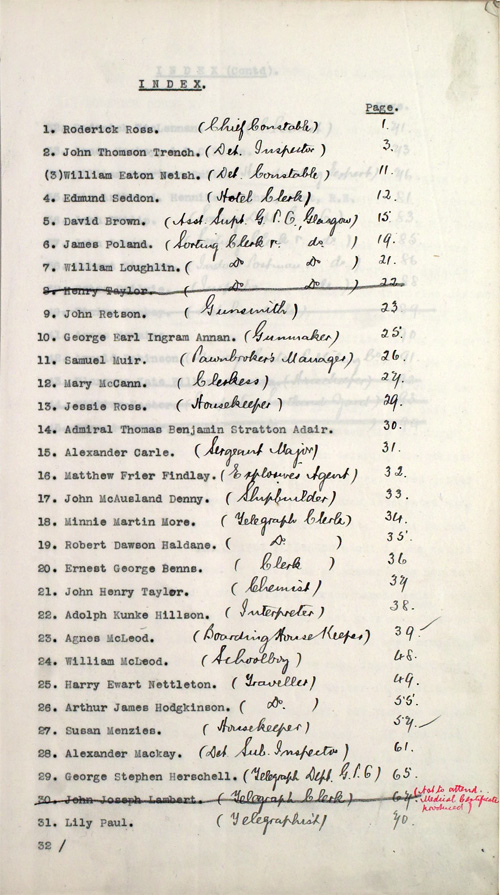

The trial in the High Court on 22-23 July 1912 attracted wide interest. Graves conducted most of his own defence, later claiming to have got the better of the retired officer, Rear Admiral Adair, who oversaw naval gun production at Beardmore's. Many witnesses, from his landlady to Post Office officials, testified to the implausible lies that Graves told about his reasons for being in Scotland, the blatant interest he took in naval affairs, his constant anxiety about his mail being delayed or interfered with, and his failure to find work. While they remarked on his odd behaviour, they mostly found Graves to be a friendly, talkative man.

List of witnesses in the trial of A K Graves, 1912

National Records of Scotland, AD15/12/44A

It was difficult for the Crown to do more than demonstrate that Graves possessed certain information about naval matters and used pre-arranged secret codes for communicating it. The facts about the guns at Beardmore's were well-known in naval circles and obtainable in reference works. Although Graves was convicted, the sentence of 18 months' imprisonment was lenient compared to the maximum penalty of seven years.

'A regular black sheep'

The trial lifted the lid on some of the bizarre life of the man calling himself Dr Graves. The South Australian police reported that he had arrived in New South Wales in 1909, posing as a French doctor, Dr Rene Sardon or Sardehn. Having committed a fraud he moved to South Australia in 1910 under the name Charles R Greve.

At first he sold insurance, then for several months as Dr A K Graves he acted as a doctor for a rural hospital in Truro, South Australia. In November 1910 he departed suddenly via Adelaide, leaving a trail of unpaid bills. In December while on his way back to Europe he was convicted of molesting a woman in Colombo, Ceylon. All this led Captain Kell to describe him as "a regular black sheep".

In Scotland Graves variously claimed to be Australian, to have served with the Australian forces during the Boer War, and to have been a ship's surgeon for seven years. However, he was probably born around 1882 in Germany and left in 1898. His later claims to have trained as a doctor, and to have carried out various missions as a German agent in South Africa and Europe may contain some truth. He was certainly a convicted fraudster when German intelligence recruited him in 1911.

'Information of the utmost importance'

After his imprisonment at Barlinnie, Graves requested an interview with "an accredited, and in Secret Service Affairs a well informed official of the War Office" to convey "information of the utmost importance". In interviews on 9-10 September he revealed to Captain Kell the names of the intelligence chiefs in Berlin. He also made the outlandish claim that they had instructed him to blow up the Forth Bridge, and recruit men for other terrorist acts.

Being convinced of the existence of an extensive German spy network in Britain, Kell was deceived when Graves, the practiced fraudster, told him what he wanted to hear, with detail worthy of spy fiction. He rewarded Graves with the offer of an early release from prison if he would work as a double agent. Graves accepted and in December 1912 he was secretly transferred to Brixton prison, received a royal pardon and was quietly released.

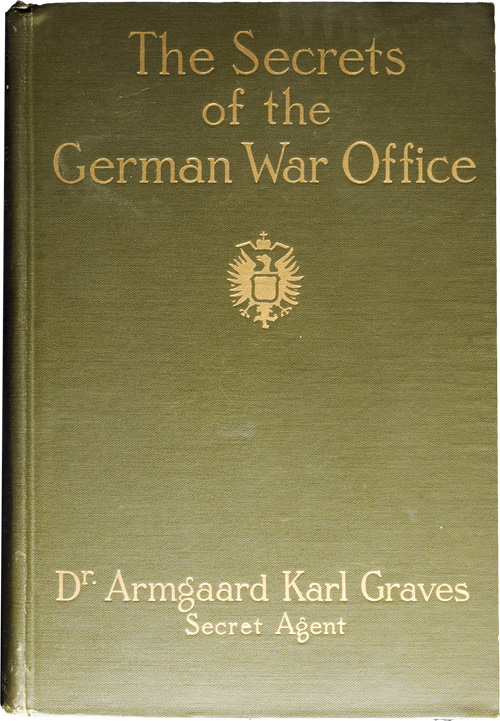

Secrets of the German War Office

Graves was one of the first double agents in modern history. His first mission in 1913 was to hunt the German spies he claimed were active in Britain. This took him from England to Berlin, and thence to the United States in pursuit of a spymaster whom he said possessed a list of the agents. His repeated demands for funds, with nothing to show for the money, made Kell realise that Graves was utterly untrustworthy. In addition, his release from prison became known in the press, and caused the British authorities embarrassment.

Cover of The Secrets of the Germam War Office by Dr Armgaard Karl Graves. National Records of Scotland.

Graves seized his opportunity for self-promotion and in August 1914 published his autobiography in Britain and America just as war broke out in Europe. In 'Secrets of the German War Office' he presented himself as a resourceful and successful agent who was betrayed by his German employers during his Scottish mission. He may never have learned that his clumsy spying had been monitored from start to finish.

While in America Graves did not change his ways, and was sentenced to three years imprisonment for fraud. On his release from Tennessee State Penitentiary in 1937 he tried to resist deportation to Germany, fearing he would be harmed. According to an Associated Press report dated 5 May 1937, federal officials at Ellis Island put him on board the passenger ship Deutschland bound for Hamburg. What became of the Kaiser's spy after that?

Further reading: Thomas Boghardt, 'Spies of the Kaiser: German Covert Operations in Great Britain during the First World War Era' (2004). For more information about the archives featured in this story, see our Crime and Criminals, Shipbuilding and Maps and Plans research guides.