Scottish Prisoners of War 1914-1918

Scottish Prisoners of War 1914-1918

From the start of their captivity Scots held prisoner by the Germans during the First World War experienced what has been described as a ‘war behind the wire’. In common with their fellow prisoners from the other home nations, the Empire and Allied countries, they tried to maintain their own military identity, resist their captors’ authority and impede the German war effort. The POWs’ war was also an internal struggle, during months or years of often gruelling captivity, to maintain their own morale, their health and even their sanity.

Private 1043 Alexander McGregor, 1st Gordon Highlanders, in POW uniform, Sennelager II camp, 1916 (NRS, GD50/184/112/7/2/1)

Most British troops were captured on the Western Front. Significant numbers were taken by Turkish forces in the campaigns at Gallipoli in 1915, and in Mesopotamia and Palestine during 1917 and 1918. They were held in worse conditions than POWs in Germany. Many troops also became prisoners of the Central Powers during the fighting in the Salonika campaign, 1916-18. Here the focus is on Scottish ‘other ranks’ captured in France and Flanders by the Germans.

Some of their stories can be glimpsed through a range of official and private archives held in National Records of Scotland. They include the wills of hundreds of Scots who died as POWs, particularly in the months before and after the Armistice. These sources may provide helpful leads in the search for prisoners of war, and they complement the military records that can be found in The National Archives at Kew and in other archives, libraries and museums.

Unidentified family of a Scottish prisoner of war, circa 1916-18 (NRS, GD50/184/112/7/2/3)

Capture

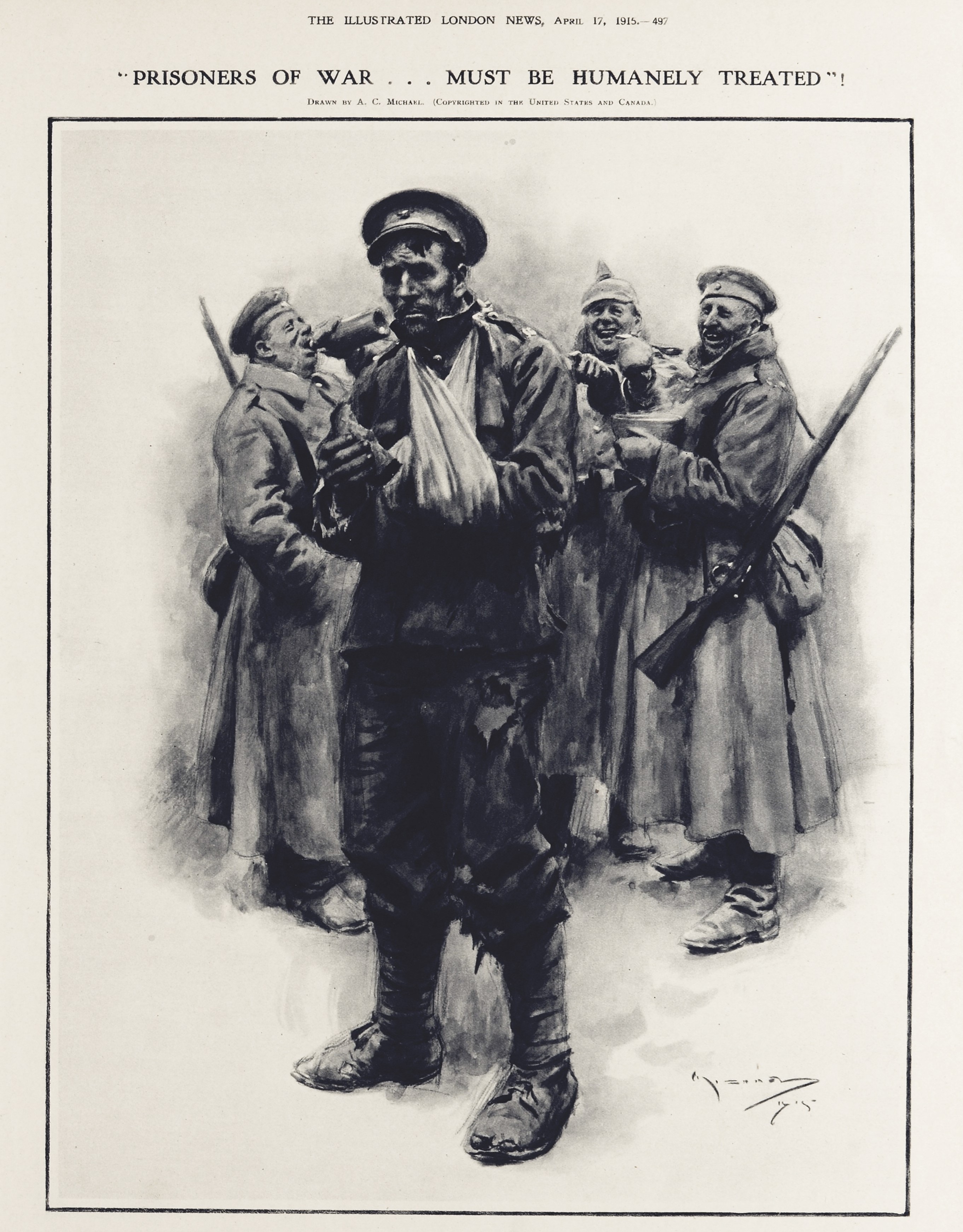

Prisoners of war are among the least studied subjects of the First World War, yet most families in wartime Britain would have been directly or indirectly aware of the predicament of the many thousands of captive servicemen. Families and friends were widely involved in the humanitarian efforts to support the prisoners. The POWs’ plight became a long drawn-out drama, caught up in the diplomatic and propaganda war that ran parallel to the military conflict. From the start of the war the British press reported examples of German cruelty towards their prisoners.

A hungry Tommy is mocked by his German captors, an image that was reprinted for propaganda purposes (‘Illustrated London News’, 17 April 1915, p.497, NRS, BR/PER/S/34/113)

British soldiers were mainly captured during two phases. Between August and October 1914, during their initial advance through Belgium into France, German troops captured more than 18,500 men of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), including many in Scottish regiments. During the German Spring Offensive of 1918, more than 100,000 British soldiers surrendered. If men captured during British attacks and German raids on British trenches at other times during the war are included, the total number of British prisoners amounted to at least 170,000, and was perhaps as high as 185,000.

In 1914 the worst-affected Scottish unit was the 1st Battalion, Gordon Highlanders. On 26 August 1914 more than 600 of its officers and men were captured in the confusion of the defeat of the BEF at Le Cateau. In October the second battalions of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders and the Seaforth Highlanders both fared badly. In accordance with international convention, the Germans separated officer prisoners from the other ranks as soon as possible and marched them to the rear. Both groups suffered privations in the process, because there was usually insufficient provision of water, food and shelter. Although there were many instances of humane treatment, contemporary reports and later accounts testified to the vindictive behaviour of German soldiers and civilians towards newly-captured soldiers. Wounded officers and men were usually given medical attention after the German wounded, irrespective of need. The fortunate ones were taken to military hospitals.

Will of Lance Corporal John Stobo, 6 Aug 1914 (NRS, SC70/8/90/31)

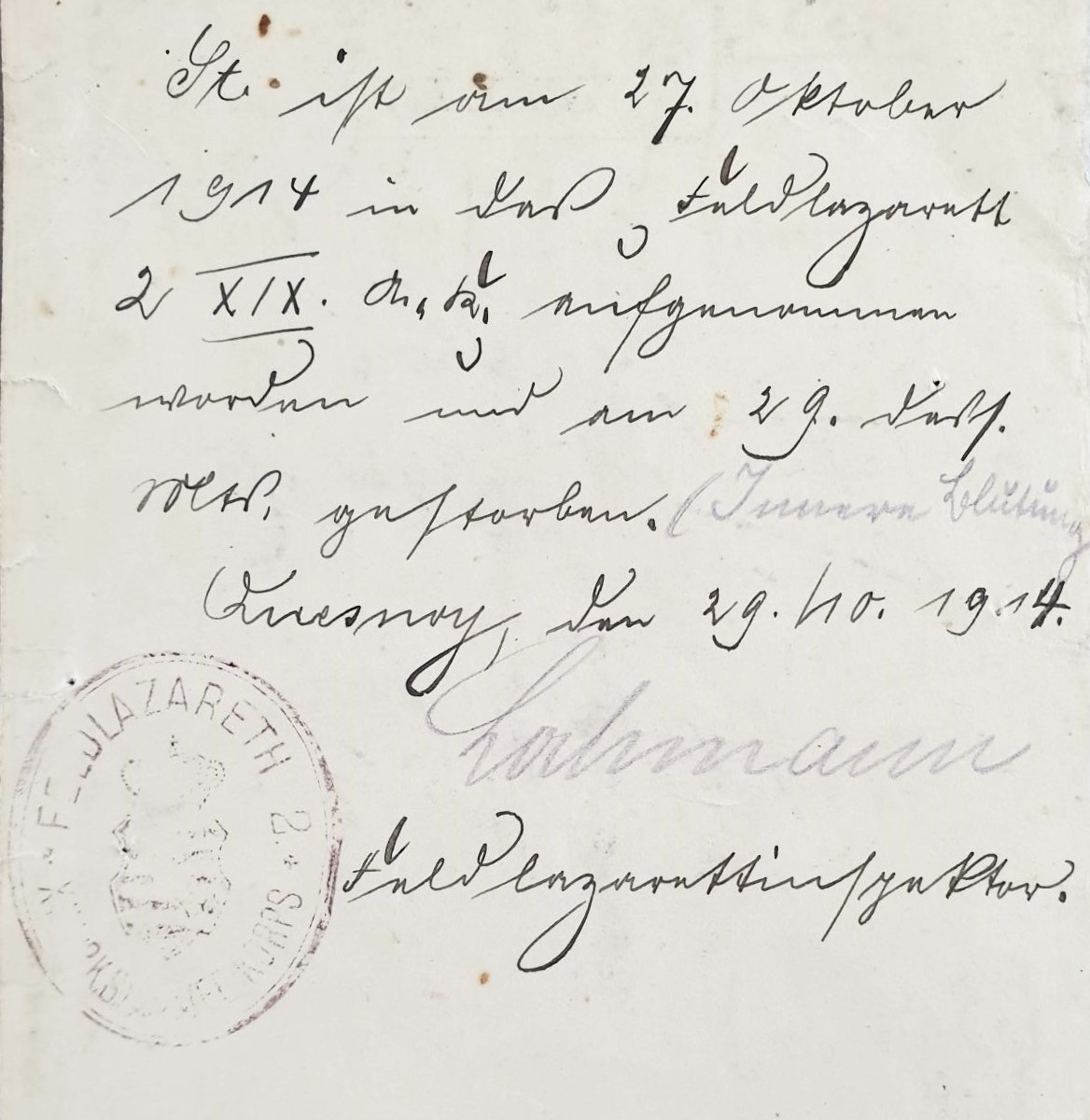

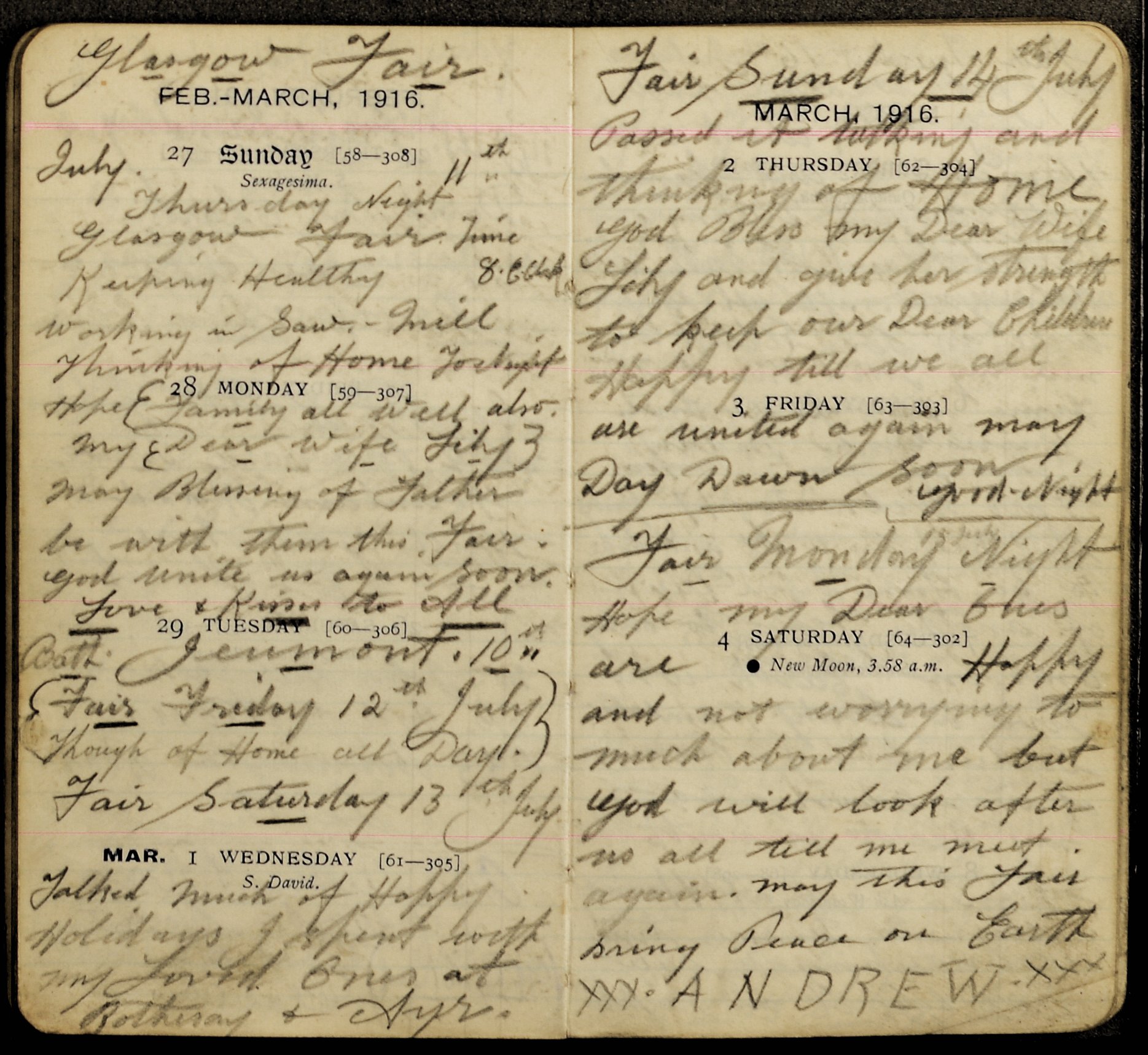

Lance Corporal John Stobo, 2nd Battalion, Seaforth Highlanders, was wounded and captured in autumn 1914. Born in 1894, one of ten children of Alexander Stobo, a printer, and his wife Agnes, John was a trunk maker in Glasgow before he enlisted in 1912. On 6 August 1914, between mobilization and embarking for France on 23 August, he made his will leaving everything to his mother. The back of the document tells of his death in a succinct note by a German medical officer, to the effect that Stobo was brought to the Second Field Hospital of the XIX German Army Corps, where he died of internal bleeding on 29 October 1914. He was buried at Quesnoy-sur-Deule, between Armentieres and Lille.

Captivity

‘We should never forget that whether the prisoner is treated in strict justice or with gross cruelty and injustice, his lot is a miserable one.’

(‘British Prisoner of War’ magazine, Dec 1918)

Scottish troops experienced the same conditions and treatment as their fellow prisoners of the home nations. Both officers and men suffered from hunger, occasional ill-treatment and the psychological torment of having been captured. Their experiences differed in one vital respect: captured officers did not have to work, but most other ranks could be put to work by their captors. The work was not to be directly connected to the war effort, and prisoners were to be paid. Conditions for most other ranks were harsh because of their inadequate diet and the work they were forced to do. Whether prisoners survived or died also depended largely on the attitudes and conduct of the camp commandant, and his officers and NCOs. The regime and physical conditions varied enormously between camps.

Some of the 89 prisoner of war camps for other ranks (‘Kriegsgefangenenlager’) could hold tens of thousands of men in wire-enclosed rows of barracks or huts. In practice many prisoners were based in satellite work camps (‘Arbeitslager’) in order to carry out labour in coal and salt mines, quarries, factories and other industrial works, as well as on farms. Local work units were known as ‘Arbeitskommando’, and might be placed in dangerously exposed conditions behind the front line, where POWs repaired railway lines and carried out other labour. In May 1916, in retaliation for German prisoners being made to do such work behind the Western Front, the Germans moved 2,000 British prisoners to work behind their Eastern Front in territory captured from the Russians. As in other camps, many deaths occurred there from overwork, malnutrition, disease and accidents.

War Office envelope containing Private James Brown’s will, 1917 (NRS, SC70/8/604/28/1)

One victim was Private 18807 James Brown, a volunteer in 12th Battalion, Highland Light Infantry, who was held in Friedrichsfeld POW camp near the River Rhine, but died on 22 March 1917 ‘whilst on Commando’. His death in an unnamed German work camp or ‘Commando’ is confirmed by other sources. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission records his burial with other POWs at Meza in Jelgava, in modern Latvia. The International Red Cross records include two lists of prisoners who had died, both dated 10 August 1917. In one Brown is said to have died following illness, in the other that he ‘died in a self-inflicted accident whilst on a work deployment’. His body was later moved from its original burial place in or near Appusen in the district of Goldingen, Kurland (modern Apuiza near Kuldiga, Latvia) (ICR Archives, PA13848 and 13855)

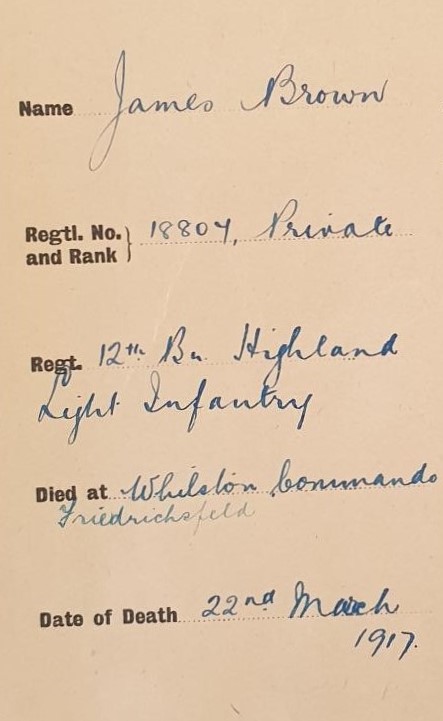

Diary of Private Andrew Clingan, working in a saw mill and recalling past family holidays during Glasgow Fair, 11-15 July 1918, (NRS, RH23/10/1/28)

By contrast, the experiences of Private Andrew Clingan, who was captured in April 1918, were much happier. At first he was put to work on railway lines behind the new German front line, then as a hospital orderly in a military hospital, where he earned praise from a German doctor. Later he was moved east and worked in a sawmill. Clingan lost several friends to disease, but survived his own periods of ill health. His war ended at Meschede camp, from where he travelled west and reached the Allied forces occupying Cologne after the Armistice. His adventures, and the intense pangs of separation from his beloved wife Lily and their three children, are poignantly recorded in a diary he kept during his captivity.

Andrew Clingan’s wife Lily, with their children Andrew, Margaret (Peggy), and the infant Jeanie, circa 1917 (NRS, RH23/10/5)

Clingan survived partly because he was fortunate to enjoy a better diet when he was working, but he still often went hungry. In the early months of the war, food parcels were not yet an established means of helping to keep the prisoners of war alive, and undernourishment was a great problem. During winter 1914-15 an English civilian eyewitness reported passing a POW camp ‘in which there were some Highlanders who were practically bags of bones’ (NRS, GD433/2/250/6-7, Oswald Balfour to Joan Balfour, Feb 1915).

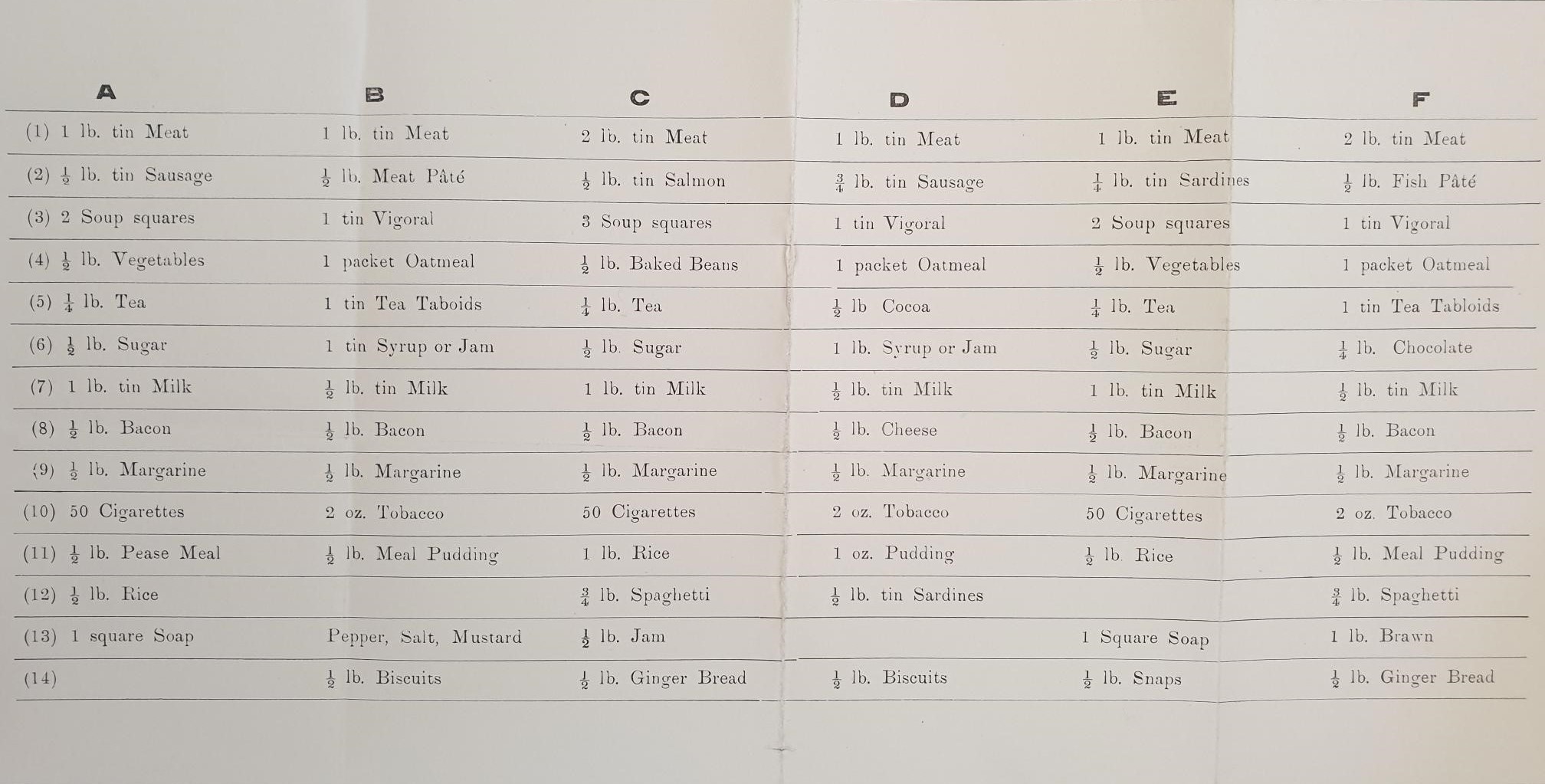

Family and friends started to send food parcels to their loved ones. This provision became more organised as regimental and local aid committees took on the role of collecting funds and assembling parcels. In 1916 the government stepped in to ensure fair access to aid sent from Britain. The Central Prisoner of War Committee co-ordinated the making-up and sending of parcels from Britain, as well as from the Red Cross in neutral Denmark, where bread was baked and sent to the German camps.

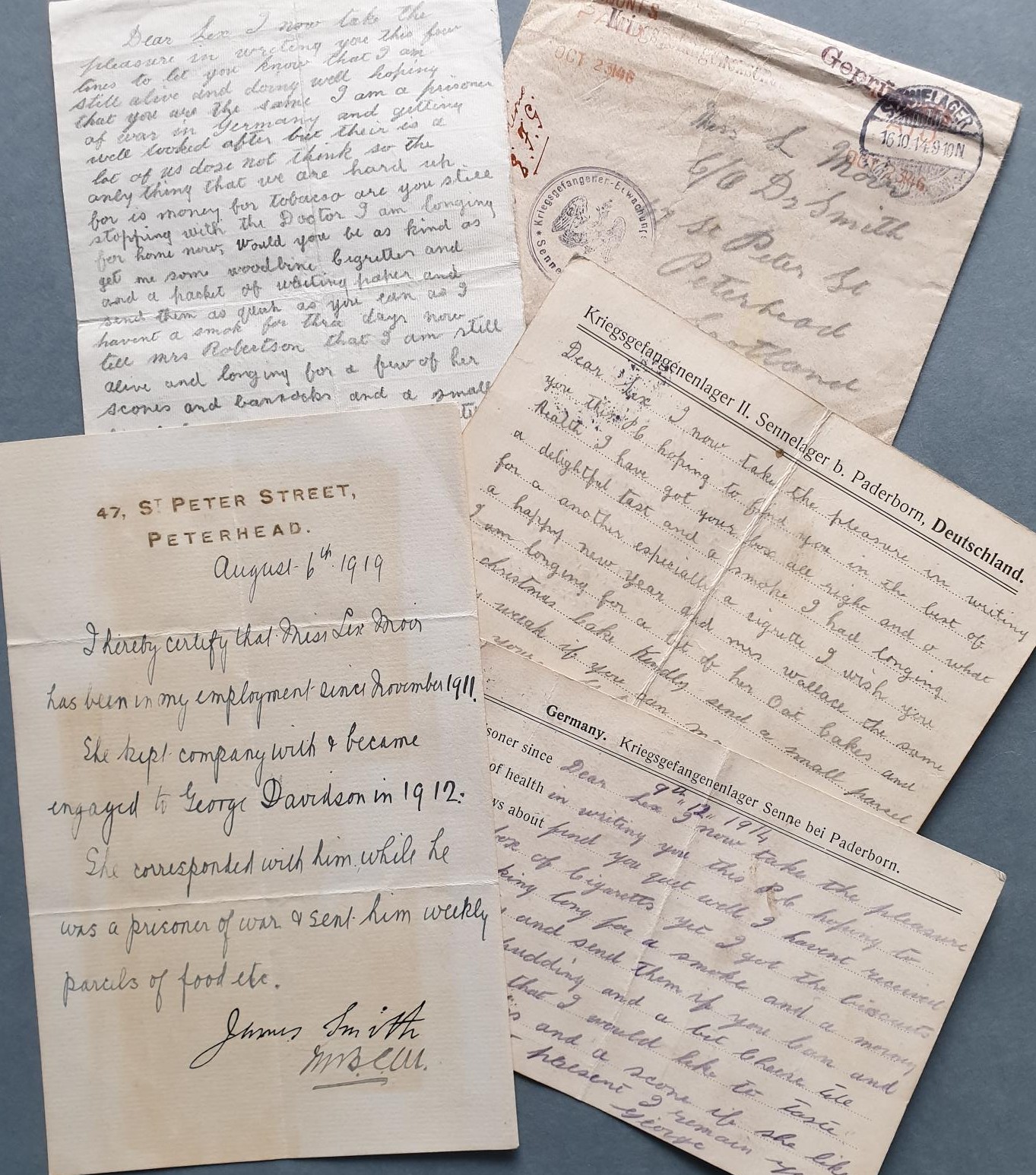

By providing food, tobacco, clothing and reading matter, well-wishers at home gave POWs of all ranks both psychological and physical support. Private George Davidson, 1st Battalion Gordon Highlanders, was captured in 1914 at Mons, and sent to one of the camps at Sennelager. He was supported throughout his captivity by Lex Moir, his fiancée in Peterhead, who spent much of her servant’s wages on food parcels and cigarettes for him. Read more about their story in the NRS Blog.

George Davidson’s messages to Lex Moir, 1914-c1916 (Crown copyright, NRS, E861/2330)

Food parcel options for sending to POWs, circa 1917 (NRS, GD50/184/112/4)

In 1916 Private 9696 William MacGregor, Royal Scots Fusiliers, wrote from Parchim camp in Mecklenberg, to thank the Clan Gregor Society for sending him cigarettes and tobacco. He hoped they could also send him ‘Dubbin’ waterproofing and hobnails for his boots. Having been born in Pretoria in 1887, and with no next of kin in Scotland, he must have appreciated the support. He claimed to be ‘in the best of health’, although the strain of captivity since 1914 can be seen in his face, as it can in many prisoners’ photographs.

Private 9696 William MacGregor, Royal Scots Fusiliers, circa 1916 (NRS, GD50/184/112/7/2/2)

In June 1918 Company Quarter Master Sergeant Albert E Borland underlined the vital importance of aid parcels in a letter to the organiser of the Prisoners of War Care Committee of his regiment, the Royal Scots Fusiliers (RSF). Only five days earlier he had been transferred to internment in Holland from the last of three German POW camps. Having been a prisoner for twenty-three months, Borland was in a good position to comment on the starvation experienced by Russian POWs, who did not receive aid from home. British officers and men would share their food with the Russians. Borland wrote:

‘You know, of course, that without our parcels from home, life would have been impossible. Hundreds of Russians died of starvation, but no British. With the parcels, we were almost independent of German food; in fact, one could have lived quite well on the English parcels alone. And no regiment was better provided for than the R.S.F. I saw many different regimental parcels in Germany, but have no hesitation in saying that I would never exchange two of my own parcels unopened for three of any other regiment, with their whole contents displayed.’

(Letter dated 18 June 1918, NRS, GD50/184/112/5)

Health & medical treatment

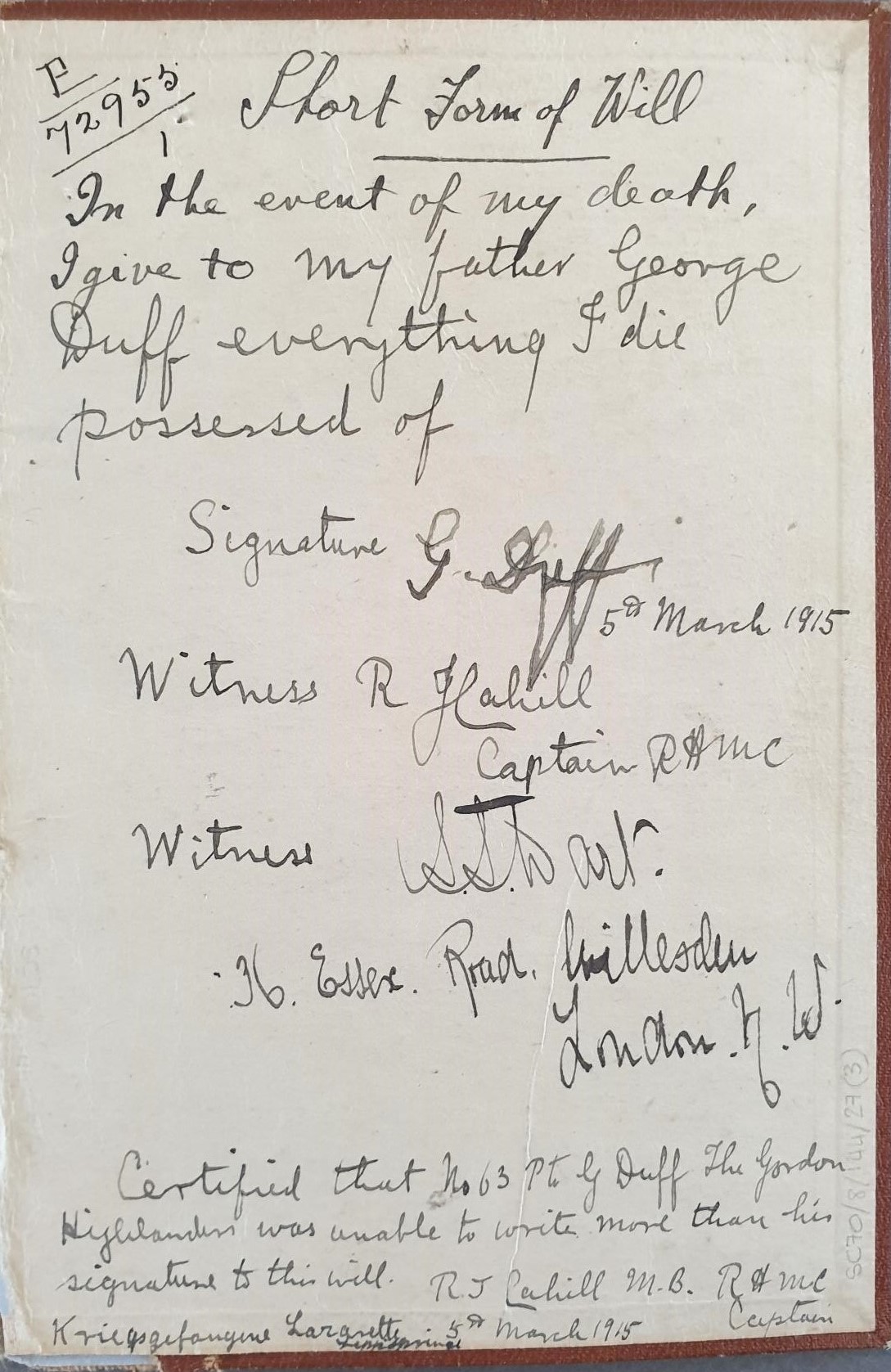

In addition to their diet British prisoners of war had a better chance of survival when Allied medical personnel were present to help them as required. The rule was that captured medical officers be returned to their own side as soon as possible, but the Germans found them useful and were slow to comply. Thus Royal Army Medical doctors found themselves battling against the effects of the poor conditions in many camps. After being captured on 11 September 1914, Captain Robert Cahill RAMC tended to sick prisoners at the German hospital (‘Lazarett’) at Lippspringe. On 5 March 1915 he wrote out and witnessed the will of one of his dying patients, a Gordon Highlander. Later that day Private George Duff died of phthisis, a form of tuberculosis. In June 1915 Cahill was part of an exchange of prisoners between the British and Germans. He continued as an army doctor, and was awarded the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) for his wartime service.

Will of Private George Duff, 15 March 1915 (NRS, SC70/8/144/27/3)

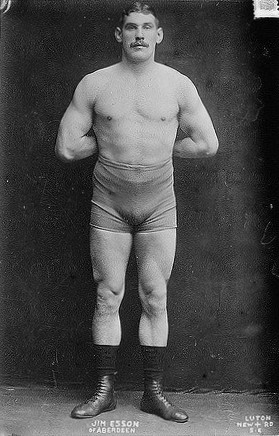

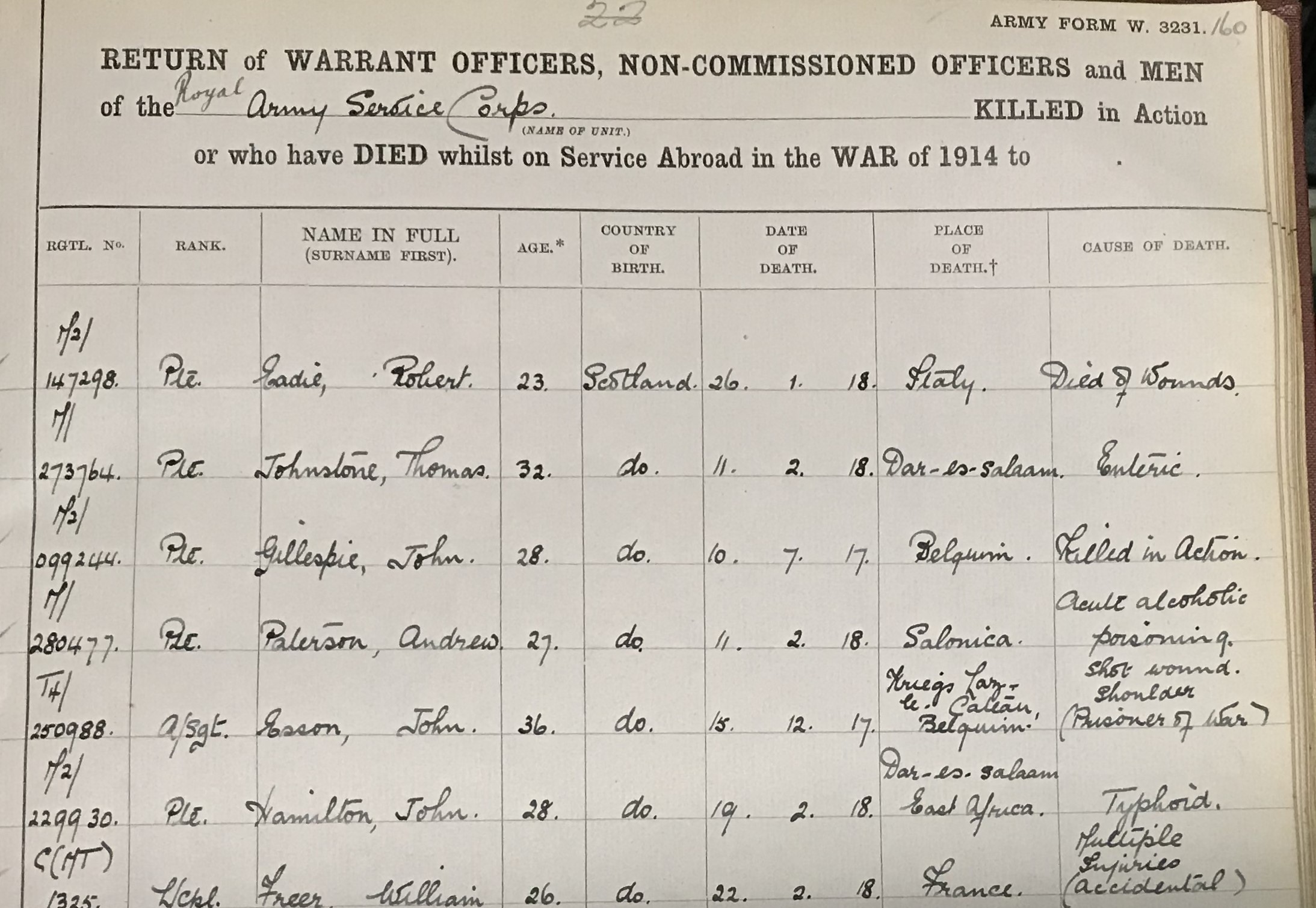

Among the many British prisoners who died in German military hospitals was Sergeant Jim Esson from Aberdeenshire. Standing about 6 feet and 3 inches tall, he was a well-known champion wrestler before the war. In November 1917 he was captured with shoulder wounds during a German counter-attack at Cambrai. According to Red Cross and Commonwealth War Graves Commission records, he died in a fortress hospital at Liege (known to the occupying Germans as Luttich), on 15 December 1917.

Jim Esson, freestyle wrestling world heavyweight champion of 1908 ('Big Jim Esson', Reddit/public domain)

Among the deaths of Army Service Corps men, that of Sergeant James Esson on 15 Dec 1917. He is misnamed John and is stated to have died in the military hospital (‘Kriegslazarett’) at Le Cateau, Belgium. (NRS, Service Returns of Deaths, Minor Records vol.132, p.160)

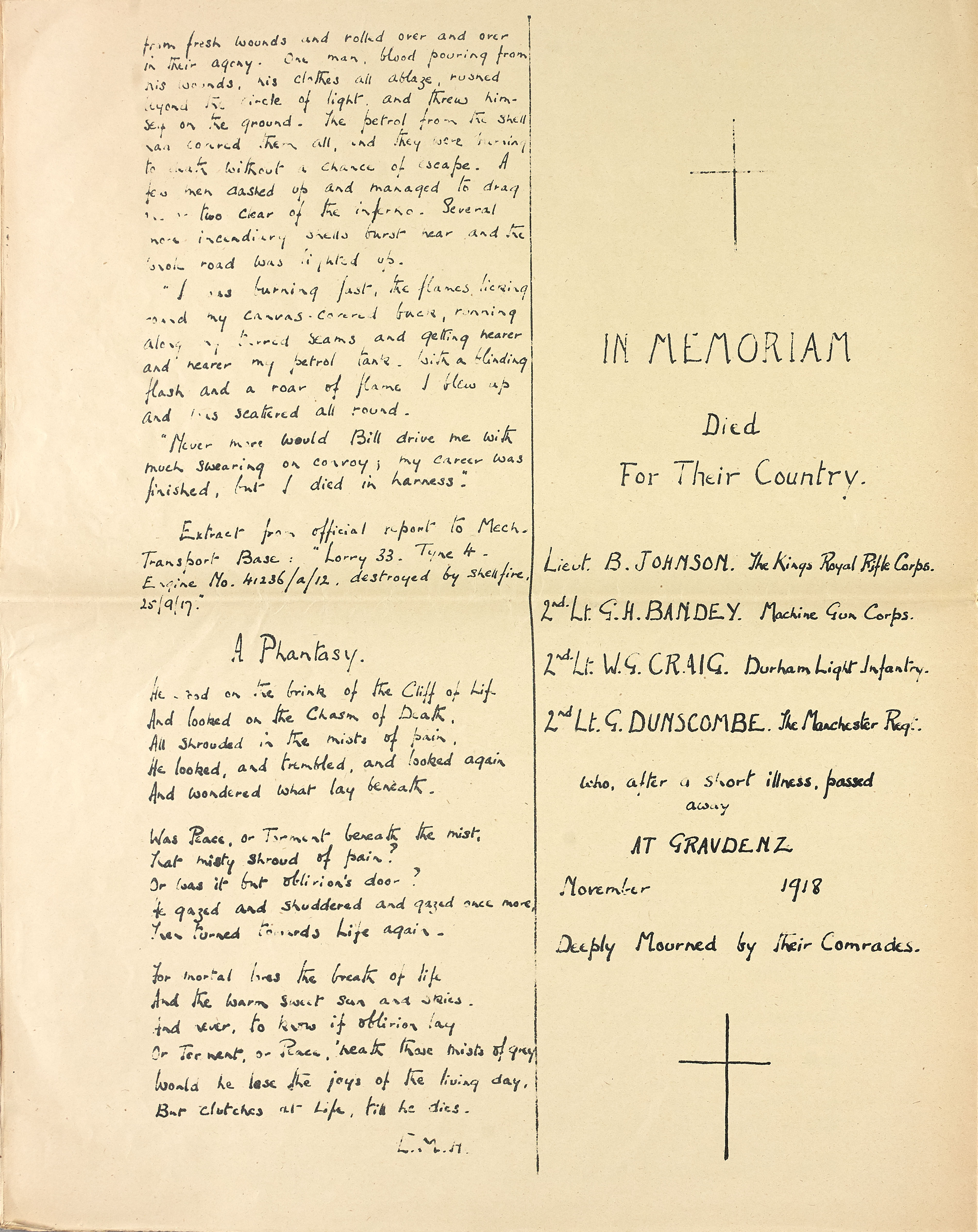

In the final months of the war the Spanish Influenza epidemic killed many POWs. On 3 November 1918, just eight days before the Armistice, and having served throughout the war, 2nd Lt Benjamin Johnston, 6th Battalion, King’s Royal Rifle Corps, died from pneumonia following influenza while still a prisoner of war. A native of Prestonpans, East Lothian, when Johnston joined up on 24 August 1914 he was a 27 year-old coalminer, married with three children and living in Musselburgh. It appears that his abilities and previous good service as a peacetime soldier in the 2nd Battalion, Royal Scots, saw his rapid promotion to sergeant in the regiment’s 12th Battalion. Johnston landed in France in May 1915 and on 26 September was gassed during the Battle of Loos. He continued with the battalion until March 1917, when he was sent for officer training. Six months later he was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in the King’s Royal Rifle Corps and posted back to the Western Front.

On 29 March 1918 Johnston went missing during the Germans’ Spring Offensive. One month later, in less time than it often took for news to reach home of a missing soldier being alive and in captivity, his wife was informed he ‘is a prisoner of war in good health in German hands.’ However, that autumn Johnston was one of four officers who succumbed to the effects of the Spanish Influenza at Graudenz camp in West Prussia. His brother officer Lt A H Gallie, who survived a bout of influenza, noted ‘Camp very depressed’. The camp newspaper ‘The Vistula Weekly Newspaper’ commemorated the four men:

‘In Memoriam Died For Their Country ….. after a short illness, passed away at Graudenz November 1918 Deeply Mourned by their Comrades’. The bodies of the four men lie near each other, and on Johnston’s grave stone are inscribed the words his wife requested: ‘In loving memory of my dear husband who died at Graudenz. Rest in Peace.’

(Service records in The National Archives, WO339/111371 and WO374/37816; A H Gallie’s album, private collection; Johnston’s will in ScotlandsPeople; Commonwealth War Graves Commission).

‘The Vistula Weekly Newspaper’, December 1918 (Lt A H Gallie’s album, private collection, image published with permission of owner)

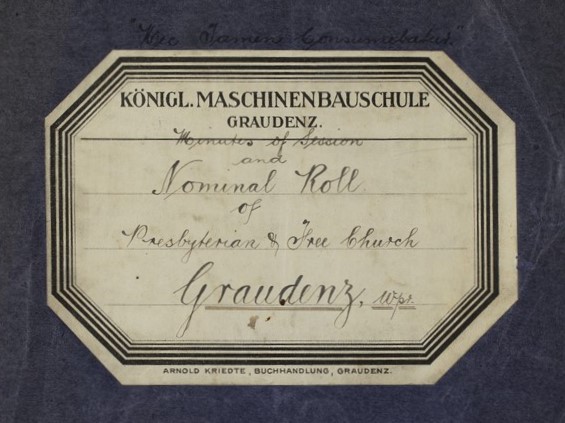

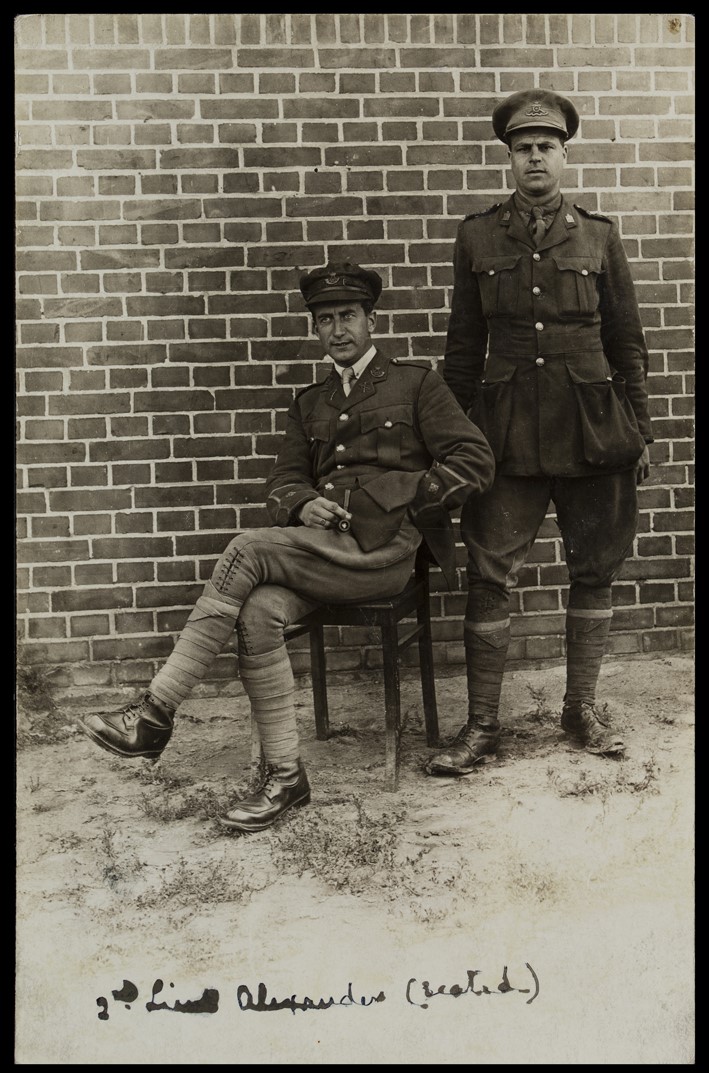

Religious faith

In every camp British POWs created a ‘church’, whether in the corner of a hut, a mess room or a tent. Sunday and weekday services were held whenever possible, often with lay preachers leading them. In July 1918, in the officers’ camp at Graudenz, about 90 Presbyterian and English Free Church members formed a congregation. Lt W Thomson Alexander, Durham Light Infantry, acted as chaplain (seen in the photograph seated beside his Anglican colleague). Alexander had earlier ministered to fellow POWs at Rastatt, and earned admiration for refusing the offer of repatriation as a chaplain, in order to continue his work with his fellow prisoners. The German garrison pastor loaned a chalice and two communion plates, while the YMCA in Berlin supplied copies of the New Testament and hymn books for 50 pfennigs each. After some initial friction the congregation arranged to share their organ with the camp’s theatre orchestra. The session clerk, Lt J W Hobbs, carefully kept the session book, which is now preserved in NRS.

Presbyterian and Free Church session book, Graudenz, 1918 (NRS, CH2/410/1)

Lt W T Alexander (seated) and colleague, Graudenz, 1918 (NRS, CH2/410/1)

Escape

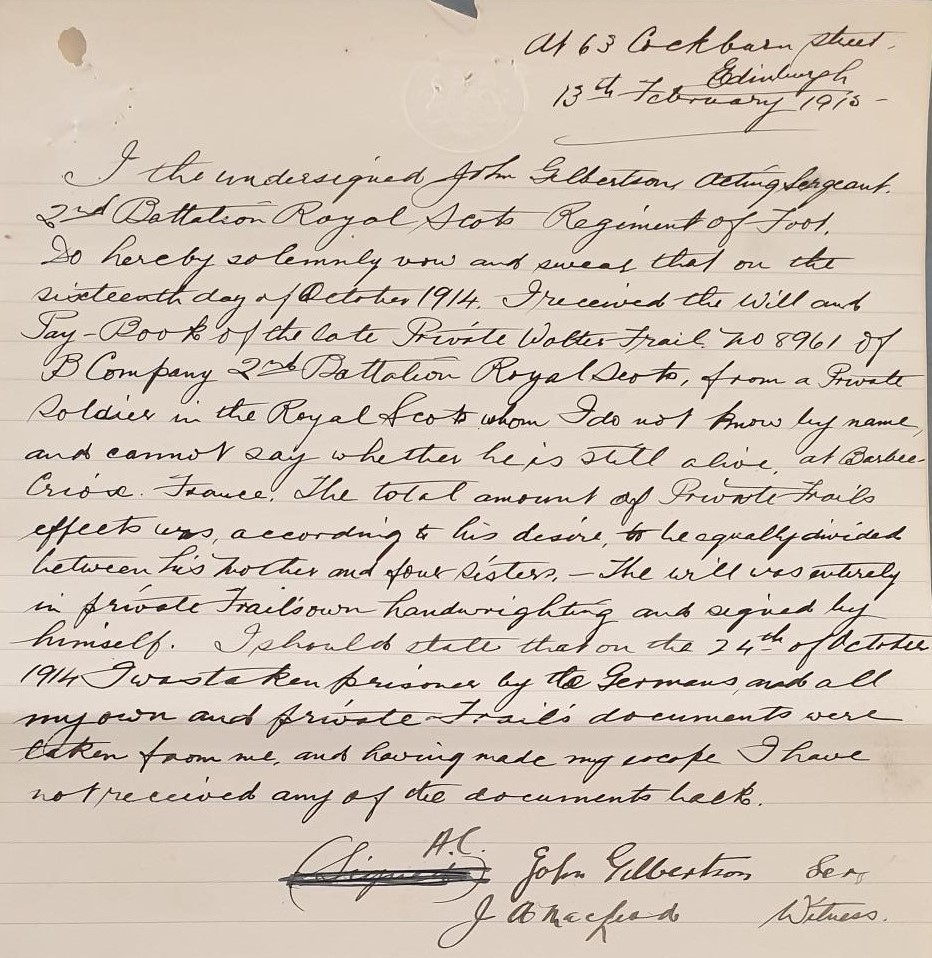

For NCOs and other ranks, the harshness of labouring for the Germans motivated them to escape. More of them than officers successfully escaped: 519 against 54. It was easier to escape from camps or ‘Arbeitskommando’ nearer to neutral Holland or Switzerland. An early escaper was Sergeant John Gilbertson, 2nd Battalion, Royal Scots, who was captured on 24 October 1914 and had escaped by February 1915. On his return he testified to the fact that the Germans confiscated various documents he was carrying, including the pay book of a badly-wounded man in his battalion who had been evacuated to England. Gilbertson is one of the few escapers documented in NRS records.

Detail of letter of Sgt J Gilbertson, 13 Feb 1915 (NRS, SC70/8/146/37)

Release

By 1918 about 40,000 wounded, sick, disabled or long-term British POWs had been sent to Holland or Switzerland under prisoner-exchanges agreed between the warring powers. They included men like CQMS Borland, quoted above. Private William MacGregor of the Scots Guards wrote on 23 June 1918 from Cassel POW camp: ‘I found a great difference in the camp now, with all our Non Commissioned Officers who were taken prisoners with us being in Holland now.’ (Card to Miss MacGregor, Clan Gregor Society, NRS, GD50/184/112/6)

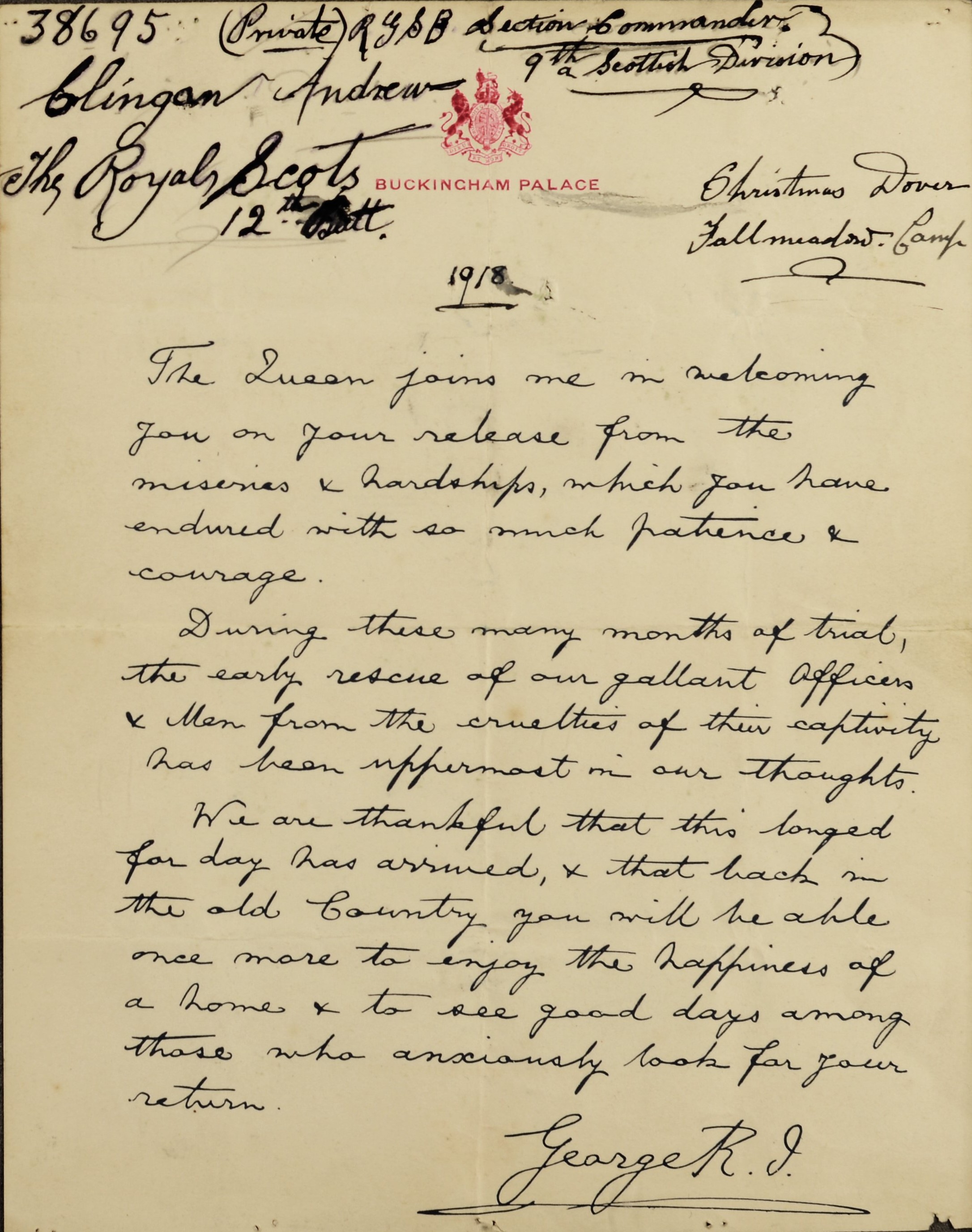

During the weeks following the Armistice the thousands of remaining British POWs, many of whom were in poor physical shape, were repatriated. They met a rapturous reception on landing at Dover, Hull and Leith. King George V, who held the prisoners of war in high regard, gifted each repatriated man a pipe and various treats. Later he approved awards to escapers. British soldiers who remained on active service on the continent awaiting leave or demobilization resented the priority given to the prisoners of war. Some even mutinied in protest. In their frustration these troops overlooked the fact that their captured comrades had faced the enemy twice: first on the fighting front and then for months or years in the ‘war behind the wire’.

King George V’s message to repatriated prisoners of war, 1918 (NRS, RH23/10/3)

An exhibition ‘ “For You the War is Over”: Scottish POWs 1914-1918’, was held in National Records of Scotland, 22 October – 23 November 2018. Courtesy of the owners of four privately-held archives, it featured documents never seen publicly before. They included the diary of Private Andrew Clingan, and many of the stories from the NRS records featured here.

If you have information about the POWs featured in this article, or other information you would like to share, please contact us.

Further reading

An invaluable published account is John Lewis-Stempel, ‘The War Behind the Wire: the Life, Death and Glory of British Prisoners of War, 1914-1918' (London, 2014).